A Martian who lands on our planet could be forgiven for believing that he had found heaven on earth after viewing the Happy Chinese New Year: Chinese Story Photo Exhibition on the eighth floor of Robarts Library.

Generously sponsored and supplied to the University of Toronto Libraries (UTL) by the Consulate of the People’s Republic of China in Toronto, the photos provide a fantastical vision of China. One picture shows members of an ethnic minority group in traditional garments as they ride horses in a picturesque river valley. Another displays children playing in a golden field as adults harvest crops by hand.

Yet, we should approach such displays with caution — this exhibition is disappointing on a number of levels, not the least of which being the misleading message it communicates to its viewers.

Firstly, the exhibit is sorely lacking in informational guidelines. It is embarrassing that an exhibition at U of T — which houses an established School of Information and a robust Museum Studies Program — comes short of the following basic elements for each artifact on display: year, place, medium, author’s biography. One can’t help but wonder if this is an innocent oversight on the part of UTL or willful negligence in order to solicit patronage from a powerful party.

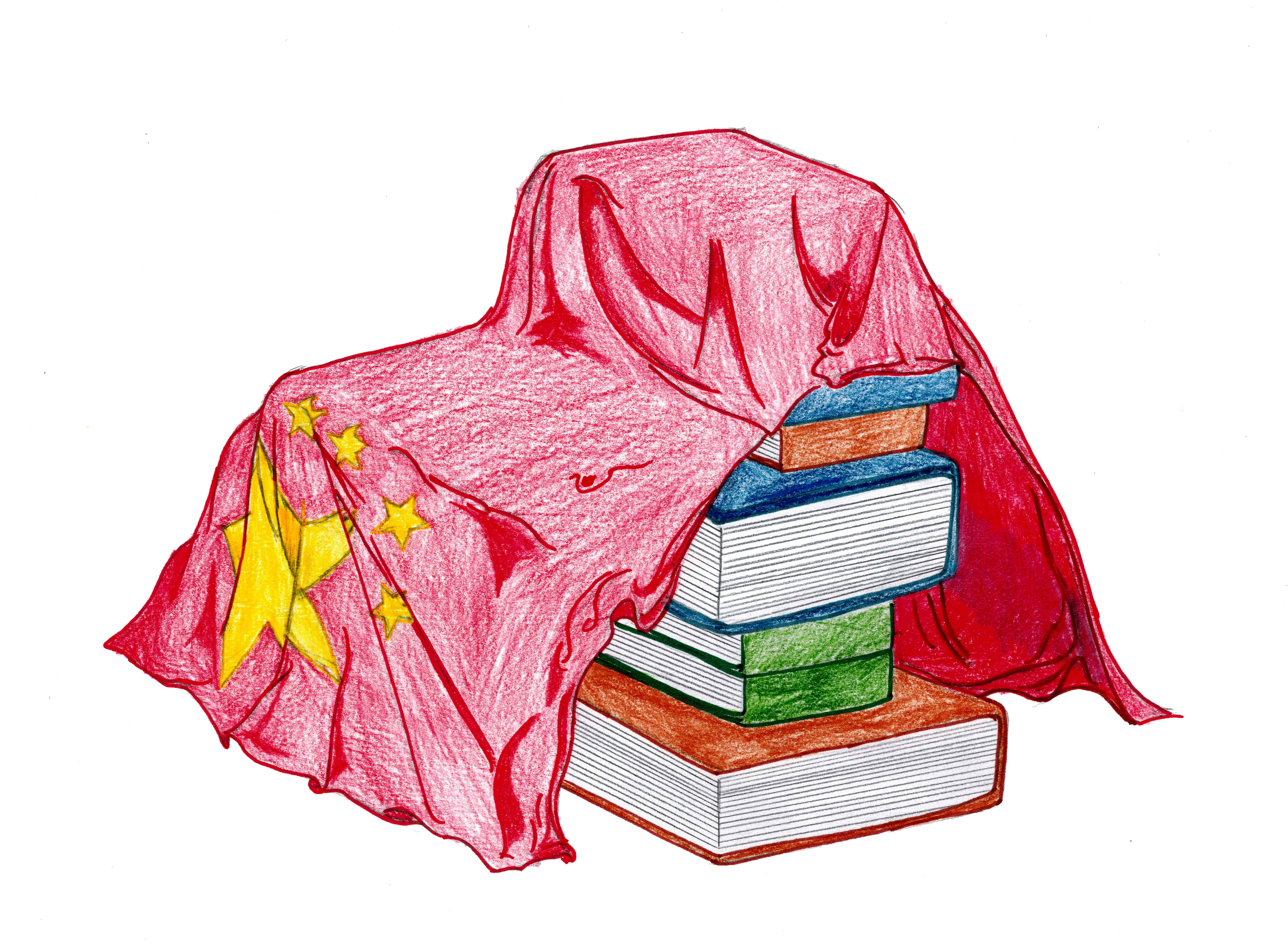

In fact, the exhibition’s title, Chinese Story Photo Exhibition, only indicates that these pictures were submitted from all over China. As the word ‘story’ suggests, the photos collectively tell a single tale of “the great endeavors in pursuit of the Chinese dream by men and women of this nation.”

This erasure of the complexity and contradiction of everyday life is a tactic used by the Chinese government to silence voices that do not reverberate with the ‘Chinese Dream’ ideology put forward by the country’s leader Xi Jinping since 2013.

The decision to allow such an exhibition to take place in an academic library is disrespectful to members of the U of T community who take their scholarship seriously. Devoid of context, history, geography, and subjectivity, the images come across as being as flat as the white foam-core boards upon which they are mounted and certainly do not encourage deeper contemplation.

The subjects and landscapes depicted may have rich stories behind them, but it is doubtful whether they can be captured in a single, postcard-like image, especially with no other information supplied.

The exhibition asks one to indulge in the superficial ‘beauty’ of the images and dwell in the dreamland of the Chinese state’s cultural propaganda. In this light, the pictures are better suited for the lobby of a mid-range hotel where faint elevator music loops in the background — but definitely not for an academic library.

I also scratched my head to understand why this exhibit is being held at the University of Toronto Libraries in the first place. Having read Robarts Library’s exhibit policy in detail, the exhibit is hardly fitting for the mandate outlined within it. It does not “showcase the scholarly output of the University community,” nor “communicate the value of the University… as an internationally significant research institution” — and it certainly does not “foster the search for knowledge and understanding in the University and the wider community.”

The only goal stated in the Exhibit Policy that is possibly relevant is to “acknowledge gifts to the Library and encourage giving.” With the People’s Republic of China being one of the world’s rising powers, it is perhaps beneficial for U of T to establish an amicable relationship with its government. But why is it that, as an academic community, we are so readily willing to be incorporated into its propaganda machine?

We would — and should — certainly object to analogous exhibits about the so-called ‘Canadian story’ being hosted abroad. As a counterpart of the current exhibit which depicts the joyous lives of ethnic minority groups in China, imagine a photo exhibition about First Nations peoples that depicted only the superficial, pristine aspects of looking in on Indigenous communities as an outsider, without further exploring their past and present marginalization.

The Happy Chinese New Year exhibit is therefore lacking on a number of levels, and we ought to expect better from the university. Instead of reading the stories in the photos, it is perhaps more interesting to investigate the story of the exhibition itself in order to gain a more critical perspective on the balance between critical inquiry and state propaganda in university libraries.

Happy Chinese New Year: Chinese Story Photo Exhibition is on display until February 10 at the Cheng Yu Tung East Asian Library and the Richard Charles Lee Canada-Hong Kong Library, both on the eighth floor of Robarts Library.

Charles Chiu is a master’s student in the Department of Geography and Planning. He is employed with U of T Libraries.

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated in order to correctly indicate the date on which the exhibition closes.