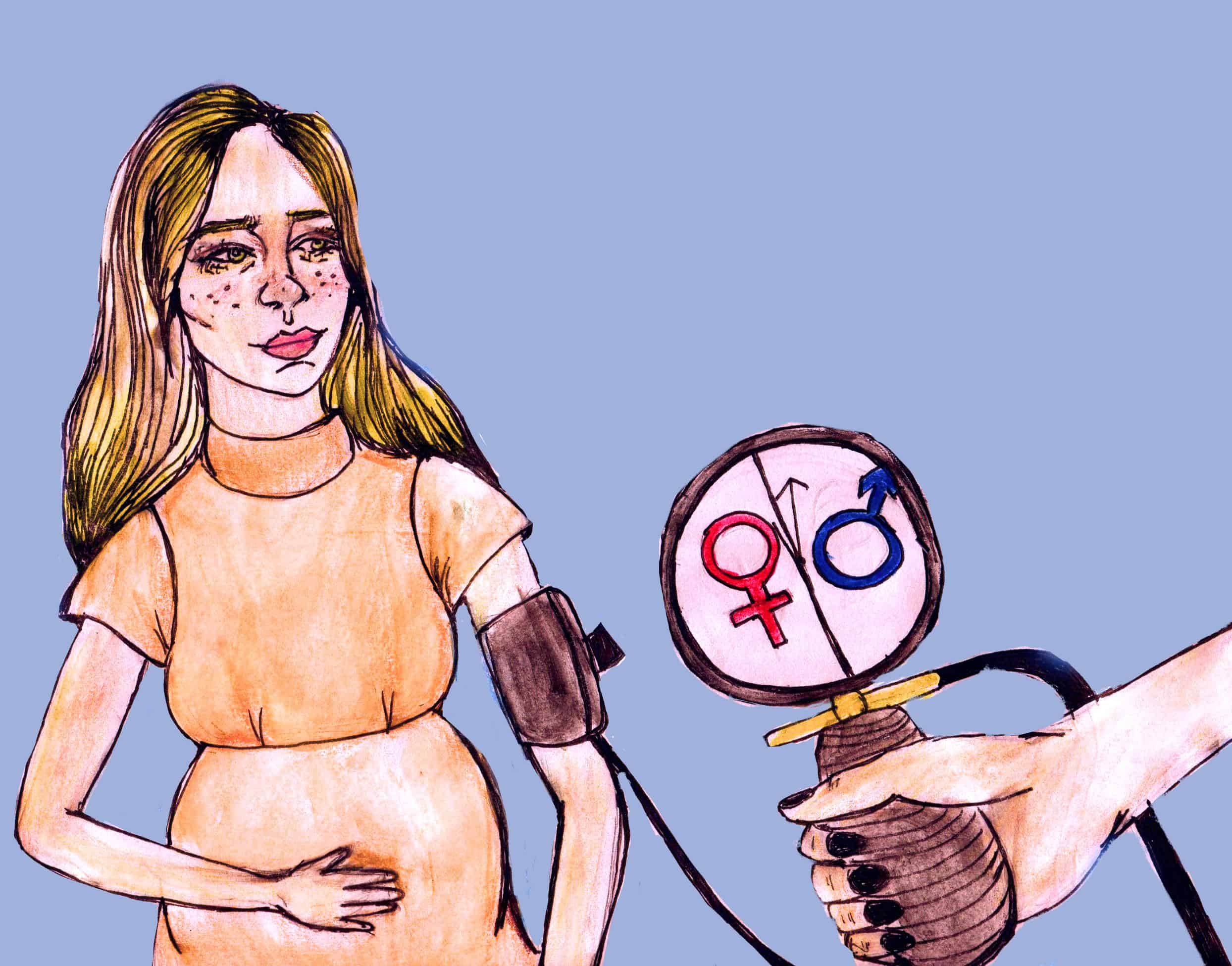

For centuries, theories about how to determine the sex of an unborn child have existed, including determinations based on the shape of a pregnant woman’s belly, her cravings, or the direction of a spinning ring. New research out of China finds an interesting correlation between maternal blood pressure and infant sex.

Researchers discovered that a woman’s blood pressure before pregnancy was associated with her likelihood of delivering a boy or a girl. Systolic blood pressure was significantly higher in mothers who gave birth to male children compared to those who gave birth to female children.

Their findings highlight the complex role that maternal physiology plays in establishing the sex ratio. “Maternal blood pressure before pregnancy is a previously unrecognized factor that may be associated with the likelihood of delivering a boy or a girl,” said lead author, Dr. Ravi Retnakaran, an endocrinologist at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto.

Retnakaran believes that certain factors in the maternal physiology are related to a woman’s likelihood of carrying a baby to term. He believes there may be some factors that make a woman more likely to successfully carry a male baby than a female baby.

Participants were recruited from Liuyang, China, where it is common for women to become pregnant soon after marriage. This allowed researchers to study women preconceptionally and to follow them throughout pregnancy. “That’s one of the reasons why we were able to find this is because we had this unique platform of a preconception cohort,” remarked Retnakaran.

In addition to their findings on the potential predictors of infant sex, Retnakaran and his group published a series of articles detailing the effect of infant sex on maternal physiology.

They discovered that carrying a boy is associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. “We all know that maternal physiology affects the baby. We did not know that it could be bidirectional in terms of the baby’s sex affecting maternal pancreatic β-cell function so we published four papers on that in the past two years,” said Retnakaran.

Over the past few decades there has been a decline in the proportion of male births in developed countries including Canada and the United States. The authors suggested that “growing societal emphasis on healthy lifestyles and a resultant beneficial impact on blood pressure in young women… may warrant consideration as a potential contributor in this regard.”

Retnakaran believes that “blood pressure before pregnancy is a marker of underlying maternal physiology,” which can help us understand the determinants of fetal loss and how to mitigate these risks in the future.

“If we could understand what are some of those determinants perhaps we could make them more modifiable. You know, we could reduce the likelihood of fetal loss,” remarked Retnakaran.