“I did not believe them because I was not even in pain,” said 33-year-old nurse, mother, and Burlington resident Melissa Benoit on Newstalk 1010, after she woke from a “last minute” double lung transplantation of unprecedented measures. For six days, Benoit was in the Intensive Care Unit of Toronto General Hospital without either of her lungs.

As a victim of the genetic disorder cystic fibrosis, Benoit has been chronically coughing her entire life. Cystic fibrosis results from a mutation in a gene coding for a salt regulator found in many of the body’s cells. Salt is involved in a complex pathway required for mucus production, and in cystic fibrosis patients, the disruption in salt regulation results in the formation of thick, sticky mucus, which causes patients to suffer complications in the respiratory, digestive, and reproductive systems.

Benoit recalls that, like other cystic fibrosis patients, she was prone to having aggravated respiratory infections which resulted in hospital visits. The dense mucus acts as a breeding ground for microbes and stands in the way of the immune system. During Benoit’s latest infection, things took a grim turn.

An antibiotic resistant bacterial attack followed by a bout of influenza left Benoit in severe oxygen shortage, or respiratory failure, as her severely inflamed lungs were filled with blood, mucus, and pus. To make matters worse, the infection had spread to the rest of her body, leaving her in septic shock — when rampant infection, or sepsis, results in a life threatening drop in blood pressure and organ damage.

Mortality rates for septic shock can be as high as 50 per cent. On Last spring, Benoit lost consciousness as a result of sepsis.

Benoit’s family agreed to have Benoit undergo a double lung removal without an organ donor in sight. Adding Benoit to the transplant list at that point in time went against hospital protocols, which dictate that patients with sepsis are ineligible for transplants.

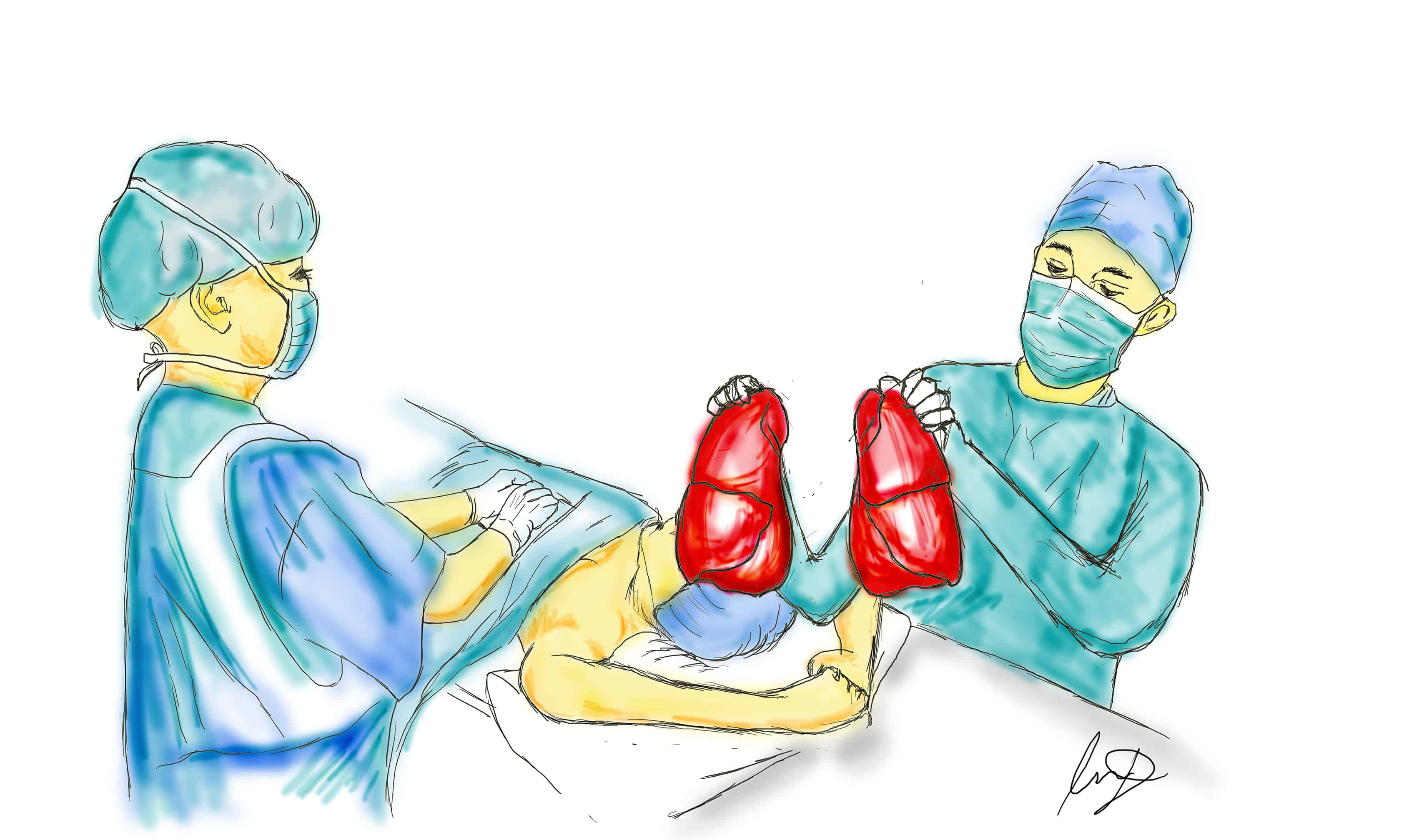

Through a nine-hour procedure involving 13 physicians, Benoit’s lungs were removed, and she was connected to a Veno-Atrial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation device (VA-ECMO), and a ‘Novalung’. The ‘Novalung’ receives oxygen-poor blood from the heart and delivers oxygenated blood back to the heart to be delivered to the body. The VA-ECMO acts as a ‘secondary heart’, pushing blood through this artificially constructed circuit.

Within 20 minutes, the sepsis showed signs of clearing, making transplantation conceivable. Although lung transplantation is not an unprecedented procedure, long-term survival rates are low, even with the immediate availability of donor organs.

It was after six days that a matching lung was found, making Benoit the person to have survived the longest period of time without lungs. During that period, doctors tried to determine whether her brain function was still intact. Benoit’s mother was insistent on getting a response from her daughter and urged her to stick out her tongue. After 20 minutes of trying, according to Benoit, she managed a little quiver which was spotted by her mother and the doctors.

Although Benoit was unconscious during the ordeal, being a nurse, she understood the gravity of her situation. “It could have been a death sentence, this trying procedure, or they could have let me have a compassionate death in the intensive care unit… it just seems so science fiction,” she said during an interview with the CBC.

Along with receiving a lifelong supply of immunosuppressants to prevent her body from attacking the new organ, Benoit had to endure months of physiotherapy before she could walk again. Additionally, her kidneys were damaged by the infection. She currently relies on dialysis to clear her body of toxins, but she is scheduled to have yet another transplant, this time a kidney donated by her mother.

Benoit’s case has offered medical professionals the confidence to attempt this arrangement with future patients in similar positions. During an interview with City News Toronto, Dr. Shaf Keshavjee, Surgeon-in-Chief and director of the lung transplant program at the University Health Network, said, “When we got into [her] predicament before, we would just sort of give up and basically talk about comfort and dying, and turn the machine off, so it is a very radical step to say… there is one more option.”