July 1 will mark 150 years since Canada’s confederation. This summer series focuses on events that explore this milestone while pondering the question: how did we get here?

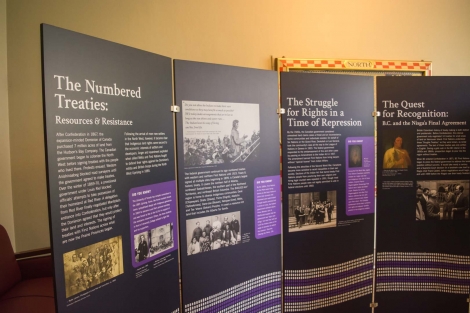

Standing quietly in the Map Room on the main level of Hart House is Canada By Treaty, an exhibit highlighting Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples through treaty negotiations. When observers first enter the room, large panels containing information about this history dominate the space.

Each panel addresses a different part of treaty history in Canada, intuitively leading viewers on a path toward deeper understanding.

Treaties

Treaties are legal agreements between the Crown and Indigenous peoples that allow non-Indigenous people to live in Canada. They were negotiated to permit the sharing of lands and resources and to place the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in a legal context. In contemporary discussions, treaties have been the subject of debate among Indigenous communities due to disagreements over the spirit and intent of specific articles in the treaty documents.

Canada By Treaty aims to educate non-Indigenous Canadians on their treaty relationships with Indigenous peoples.

From idea to exhibit

Canada By Treaty was put together by students in a seminar entitled “Canada By Treaty: Alliances, Title Transfers and Land Claims,” taught by co-curator and Associate Professor in the Department of History Heidi Bohaker.

Last year, Bohaker and her colleagues in the Department of History considered various ways of participating in the Canada 150 events and, having taught the joint seminar before, decided to help educate Canadians on their treaty relationship with Indigenous peoples.

According to Bohaker, Canada By Treaty was also a response to the 94th Call to Action in the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which aims to include honouring treaties with Indigenous peoples as part of Canada’s oath of citizenship. “What struck us is how that can happen if Canadians, new and old, don’t even know what treaties are. So some fundamental and foundational educational work has to take place,” said Bohaker. “Really this is a country built by treaty… there were no wars of conquest. It’s a negotiated place.”

After receiving $2,500 from the University of Toronto Provost, which was matched by the Department of History, Bohaker embarked on her mission to have her students curate a “loosely defined exhibit on treaties.”

From there, more funding was accumulated: the class received $10,000 from the Jackman Humanities Institute Program for the Arts Grant, as well as various donations from sponsors such as the Ontario150 Community Capital Program, University of Toronto Libraries, University College, Regis College, and the Jesuits in English Canada.

On opening day, the exhibit was attended by the likes of Elizabeth Dowdeswell, Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario, and Chief Stacey Laforme of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation, the First Nation on whose territory the University of Toronto stands.

Research intensive

With adequate funding, the students were able to expand their research with more resources and high-end materials to create the beautiful exhibit that stands in the Map Room today.

Bohaker said that she wanted the students in her class to do something more than conventional papers and presentations, although she admits that she still made them write a final term paper. “And they stuck with it, which was very good of them,” she laughed.

The students, all of whom were non-Indigenous though some were part of the Indigenous Studies program, were given the opportunity to conduct a primary source analysis of a treaty document that “they could identify with.”

On the challenges that students faced with information, Bohaker noted that they grappled with whether the story was theirs to tell, as non-Indigenous people that don’t have the same lived experience as Indigenous peoples. They had not experienced the implications of treaty relationships on Indigenous peoples’ daily lives.

“In the end, the students felt, ‘well it is part of our story to tell, we’re all treaty people, and that we have an obligation to educate other non-Indigenous people about these agreements,’” concluded Bohaker. “I’m glad we discussed that. That was an important thing to think through.”

As preparation for the exhibit intensified, Bohaker said that the class became less like a seminar and more like a workshop, as mock-ups of panels and craft materials replaced normal class activities.

Educating the public

As observers mill about the room, they will likely notice that the panels are positioned in two separate, offset semi-circles. According to Bohaker, the disconnect symbolizes our treaty relationship, and how treaty relationships are envisioned by First Nations as a relationship of equality. “The circle right now is off, right? It’s offset, so the idea is that through educating Canadians about what treaties are, we can begin the process of bringing the circle back together.”

“I think that most Canadians now recognize… a general and legal acceptance [of] multiculturalism in this country. We still have a long way to go, I think, in terms of addressing the historic and present day racism towards First Nations, and really coming to terms with what it means to be treaty people, that we are this place that was negotiated and has ongoing relationships, right?”

Canada By Treaty will stand in the Hart House Map Room until May 25, before travelling to various other venues, all free of charge.