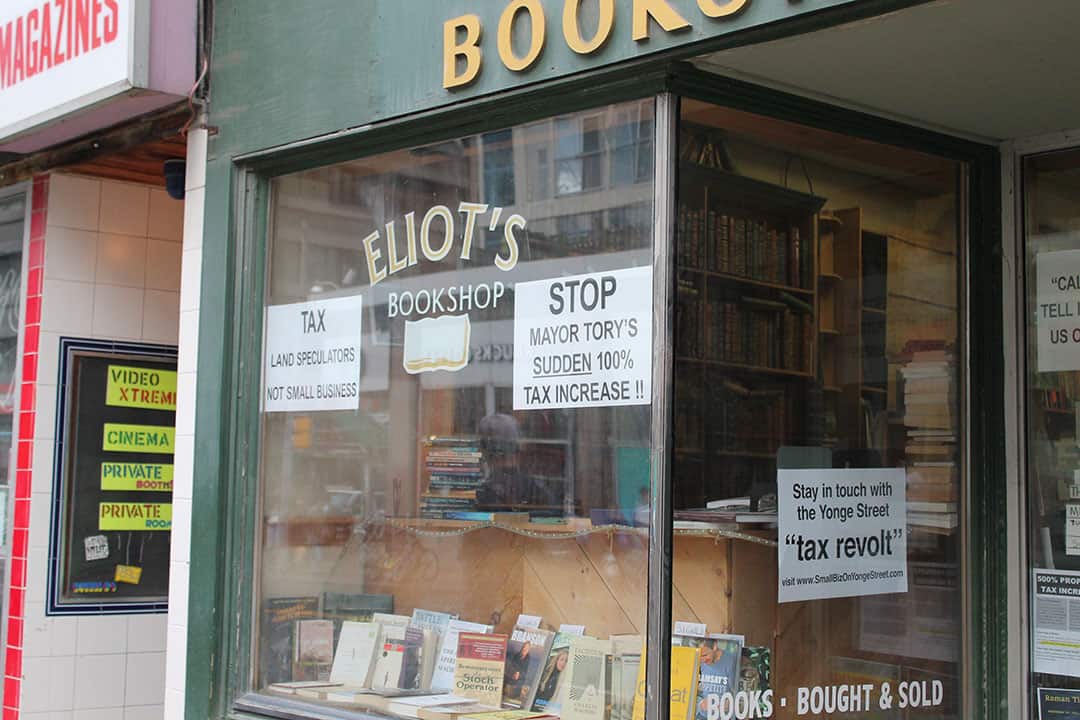

Amid the bright lights of the corporate fast food locations around Yonge and Dundas, one cannot help but notice the pervasiveness of empty windows and for-lease signs. Following a property value assessment last month, property tax rates on Yonge Street businesses are set to rise by 500 per cent over the next four years, forcing many to close up shop. Among the most notable to leave are the House of Lords hair salon, Eliot’s Bookshop, and Remington’s, Toronto’s most popular male strip club.

Recent increases to the provincial minimum wage and forthcoming federal tax increases have left some attributing the outrageous increases to a government-led war on small businesses, though Mayor Tory’s office has been quick to direct blame toward the real culprit — an unpopular provincial government.

Toronto, like every Canadian city, remains a creature of the province, finding itself constitutionally unable to generate revenue from the public outside of property taxes. Cities in countries like the United States are able to employ revenue tools such as sales taxes and road tolls. Aside from the occasional provincial or federal grant, Toronto remains bound to property taxes to fund its extensive infrastructure needs and community services. When Mayor Tory suggested the implementation of road tolls to start easing the city’s financial burden last year, the Wynne government stomped on the idea — presumably with the 2018 election in sight.

If it can avoid the media stunts of the Ford family, the Mayor’s office should work with all provincial parties to craft platforms that work for Toronto, so that the unfortunate yet all-too-common headache of skyrocketing tax rates does not occur. With a 44-person council, Toronto is mature enough to manage its own destiny, let alone its tax revenue.

James Chapman is a third-year student at Innis College studying Political Science and Urban Studies.