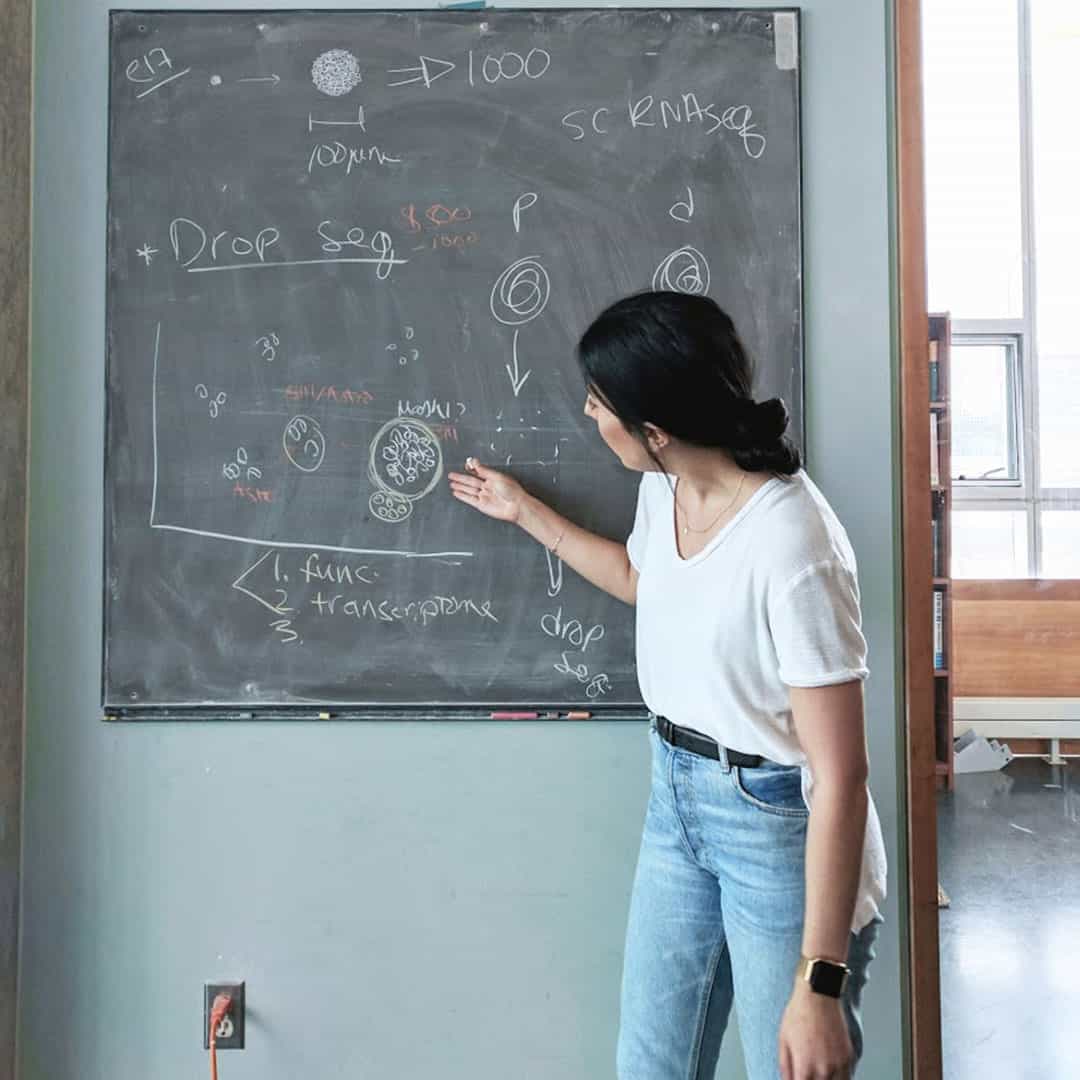

Samantha Yammine is a PhD candidate in her final year at the University of Toronto in Dr. Derek van der Kooy’s Neurobiology Research Group. She is also a science communicator.

Although science communication manifests in different ways, at its very core it’s about explaining science-related topics and research to non-experts. Scientists generally do this by stripping their research of jargon and voicing their message in ways that can be easily understood by the general public.

Yammine started out in science communication by writing tweets for the Ontario Institute of Regenerative Medicine during the second year of her PhD studies. Since then, Yammine has moved her passion for science outreach to her Instagram account, science.sam.

According to Robert A. Logan in his article “Science Mass Communication,” science communication started out in print during the first 30 years of the twentieth century in the US. Some scientists sought to educate the public about science to make rational public affairs decisions and improve the quality of their lives through science policy, public affairs, and public opinion.

The purpose of science communication hasn’t changed much since.

Yammine explained to The Varsity that by communicating her research through various social media platforms, she hopes to pique her audience’s interest in science.

“We talked a lot about policy and science policy and why communication is important so that we can have a positive impact on science policy in Canada,” said Yammine at the Science Writers and Communicators of Canada conference she attended two weeks ago in Ottawa.

At the conference, Yammine and fellow science communicators discussed the role that social media plays in this field. With the rise of Twitter and Instagram, science communicators and journalists have had to keep up with social media’s pace and influence.

Yammine regularly posts on her Instagram account, which has over 9,600 followers, and she has shared over 240 posts. She takes around 40 pictures a day, and only one or two will make it onto her Instagram. She shares pictures of brain stem cells, laboratory equipment, and different science events around Toronto. Last month, she covered the Dunlap Institute’s coverage of the solar eclipse and shared photos from the event.

“I picture my lab mates reading and I also picture my sister reading who is not in science,” said Yammine when explaining her process of posting content.

Instagram is her social media outlet of choice because she is able to share both photos of her in the lab and of her doing normal things like going out to dinner. “If people aren’t going to listen to science, it’s because the people talking about it… might not relate to them or think that they’re trustworthy,” said Yammine.

As a teaching assistant, Yammine noted that the classroom may be an intimidating setting for many students. “I think that communication needs to be taught more in science… It is a skill to learn, and I think science undervalues quality of writing to its detriment.”

Yammine stressed that learning how to communicate through writing will be useful, especially for students considering graduate school, where they will eventually author publications and write grants. “Even in a lab report, your intro has a point — you’re introducing the topic that you’re studying.”

In fact, she recommended that students learn to write concisely by using Twitter or Instagram, whose character limits force students to summarize their findings in short sentences.

Science communication has been a rewarding experience for Yammine so far. Her favorite part is receiving messages from students who tell her they are motivated by her posts. She also loves seeing posts from other young women who are inspired to pursue science.

“If you value science, and you want to combat pseudoscience and fake news, put your engagement, your clicks, your likes, your comments where your values are,” she said.