In October, Rupi Kaur’s The Sun and Her Flowers was ranked second on The New York Times Bestsellers List. Kaur’s first book, Milk and Honey, hit number one earlier this year, has sold two million copies, and has been translated into more than 30 languages.

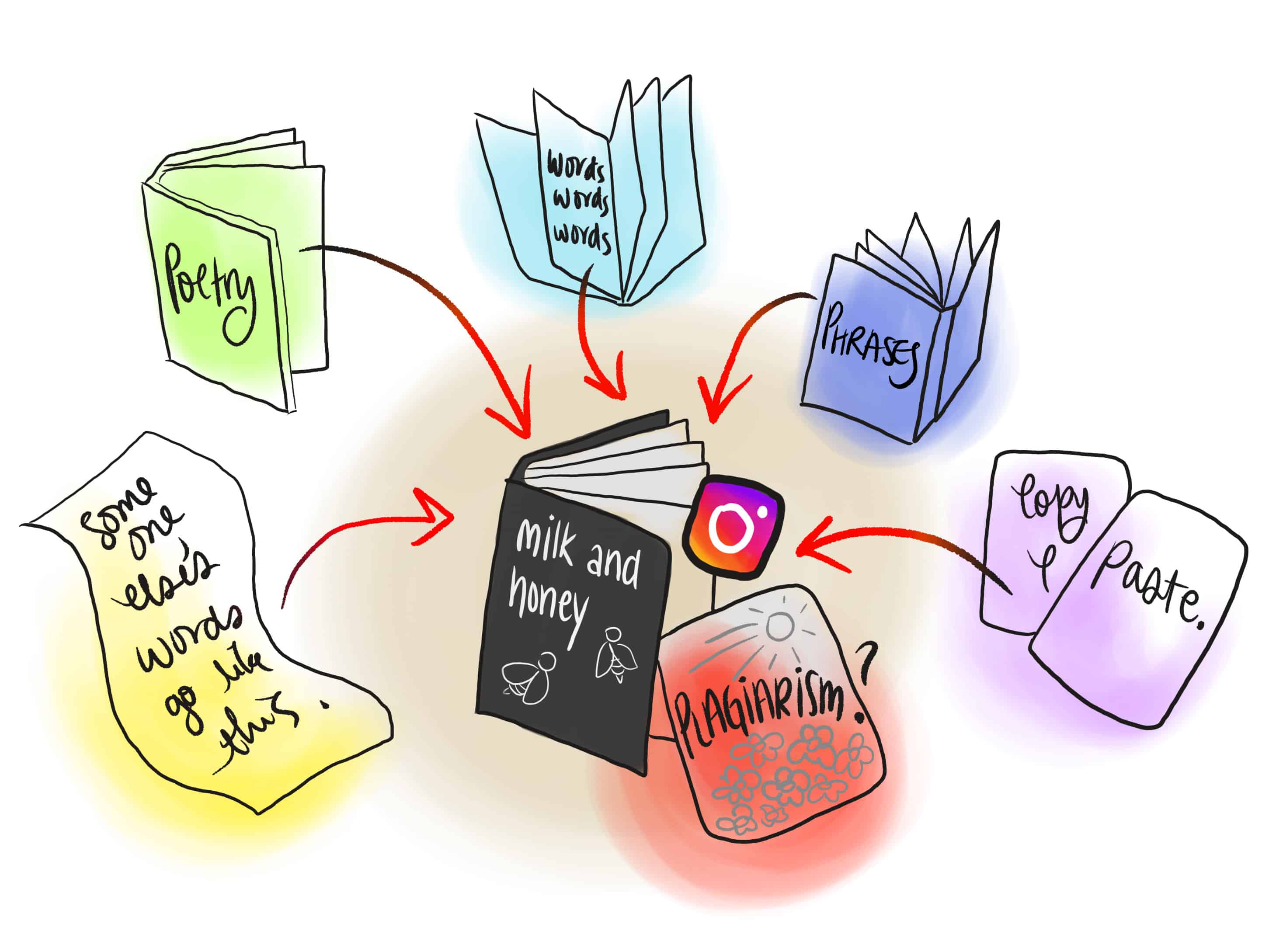

Kaur’s work has not only achieved commercial success, but has been lauded in the media. In a Huffington Post article from 2015 titled “Rupi Kaur: The Poet Every Woman Needs to Read,” Erin Spencer wrote, “Milk and Honey is the poetry collection every woman needs on her nightstand or coffee table.” This kind of attention, combined with Kaur’s massive following on Instagram — about 1.7 million strong — has assured her rapid rise. Yet Kaur’s overly simplistic, accessible poetry has provoked a discussion in both the literary world and her more mainstream audience as to whether or not her work even qualifies as poetry or constitutes ‘real literature.’

Accessible ‘poetry’

In 2016, Kaur told The Guardian that she felt that the global market did not have room to include a Punjabi-Sikh-Canadian woman’s experience with love, healing, and trauma. After achieving little success in publishing her work in traditional literary mediums like anthologies and journals, Kaur took to self-publishing her manuscript, a growing alternative to traditional publishing though still somewhat stigmatized and dismissed in the literary world. Her work to self-publish Milk and Honey in this context is indeed admirable.

The themes which Kaur explores in her work are both relatable and important. Her experiences are valid and worth sharing, and many women have been able to connect and heal from their own traumas through Kaur’s work.

Yet, despite her ability to connect with readers, I cannot shake the annoyance and frustration I have with her works being labelled ‘poetry.’ Perhaps my reaction to her notoriety is a result of my love of the poetic canon, but I also have a love for literature outside of that elite literary circle.

Rupi Kaur’s works are sentences

broken into fragments

that lack basic poetic devices

and this is where my

frustration stems from.

Literary forms and genres should be challenged. They should evolve and be made accessible to contemporary audiences — but in a way that follows at least some structural elements of its traditional form. Poetry should certainly be thought provoking, and should elicit feelings and connection. But accessibility does not mean eliminating poetic devices from the genre.

The beauty of poetry is that the poet can evoke a feeling without requiring the reader to understand the work’s message immediately. Petrarch’s sonnets may not be accessible to everyone, but they are written elegantly, filled with countless poetic devices. His poetry shows, while Kaur’s tells.

— Carol Eugene Park

Allegations of plagiarism

Despite Kaur’s success, both in terms of book sales and social media following, her work has not escaped criticism. Allegations of plagiarism and lack of originality have arisen, particularly in relation to her work’s similarities to Salt, a book by the poet Nayyirah Waheed.

Having been familiar with Waheed’s work prior to reading either Milk and Honey or The Sun and Her Flowers, I do see the similarities and I don’t think the allegations of plagiarism are completely unfounded. Thematic similarities arise in both authors’ works, like the motif of honey used as a metaphor for kindness or cooperation. Both writers also frequently draw connections between womanhood and the sea.

However, I don’t think it’s fair to assert that this alone constitutes plagiarism. These elements have a connotation that many are at least familiar with. Drawing on shared understanding is part and parcel of many genres of literature — authors use words or notions that they believe will draw on a common understanding in order to communicate their ideas.

It may not be fair to say that Kaur outright plagiarized, but there seems to be evidence of hyper similarity and even paraphrasing. Perhaps most interesting is that although Waheed reached out to Kaur both privately and publicly for a comment on the allegations of plagiarism, Kaur did not respond.

One would think that when an author is accused of plagiarism, they would refute such allegations, justify the similarities, or at least engage in a conversation. While Kaur has cited Waheed as an inspiration several times, she has never responded to the allegations of plagiarism against her. One must wonder when inspiration ends and plagiarism begins.

Disingenuous attempts at universality

Another often-criticized aspect of Kaur’s work is her attempt to be both personal and universal by generalizing her own personal confessions. Her work involves issues of rape, abuse, misogyny, violence, femininity, and body shaming, much of it related to her background as a Punjabi and Sikh woman.

In her writing, Kaur claims to represent generations of trauma, generalizing her personal opinions on these issues on behalf of the greater Punjabi and Sikh communities. This is particularly problematic because she doesn’t differentiate between herself, an educated, Indian-Canadian, Western woman, and her ancestors, or even the modern women who currently live in her ancestral hometown.

Kaur’s work suggests that all South Asian women have the same experience, and doesn’t acknowledge her own privileges or the simple fact that historical differences do exist. It’s disingenuous for her to claim that her experience is the same as that of a colonized woman, and for her to derive material benefit from claiming generations of trauma that she may or may not have personally experienced.

Discussing the accusations of plagiarism that have been levelled against Kaur raise interesting questions of originality and ownership in this digital age, where both information and art can be disseminated widely and rapidly. The criticism of her work as claiming a false universality also brings up issues of postcolonial writing and positionality. We must wonder how Western postcolonial writers can position themselves in a modern context while their writing is historically influenced, and how they can write about historical experience while ensuring they do not claim it as their own.

— Farida Abdelmeguied