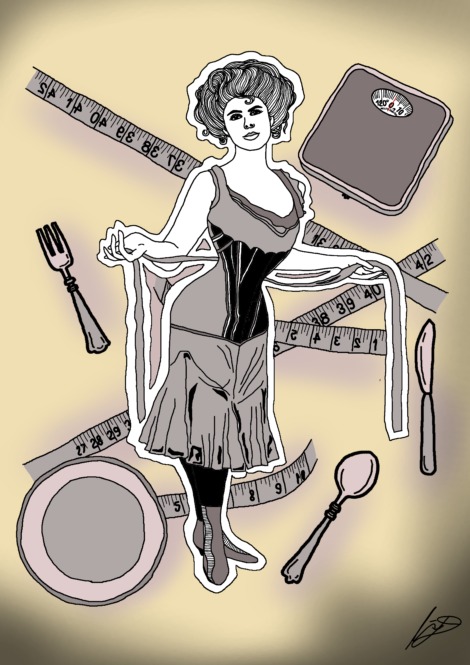

Those afflicted suffered from fevers, coughing, diarrhea, and emaciation. Yet, at the same time as it reached epidemic levels, tuberculosis became somewhat of a fashionable disease. There was a strong glamourization of patients who were observed to have pale skin, flushed cheeks, and extremely thin physiques, all attributes of the ideal female form. Regardless of the havoc that it wreaked, the appearance of tuberculosis patients was almost immediately popularized for its association with femininity.

Victorian fashion was taken over by pointed corsets with voluminous skirts, and red lips and pink cheeks against porcelain skin. Nineteenth century ‘consumptive chic’ was, in other words, an obsessive emulation of tuberculosis patients.

Thinness had become both a necessity and an aesthetic. By the end of the nineteenth century, anorexia nervosa was officially recognized as a mental disorder. Evidently, this dangerous cultural fascination with extreme restriction and thinness did not end there.

Anorexia nervosa has been in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) since its first edition. However, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder were not officially recognized until over 30 years later. Despite being relative newcomers to the DSM, both have higher prevalence rates than anorexia nervosa. Conversely, bulimia and binge-eating appear far less frequently in pop culture.

Our value-laden notion of appropriate feminine appearance and behaviour has generated a hierarchy that is reflected in media content. There are a slew of movies and books about anorexia, but seldom any about other eating disorders.

This narrow portrayal is not new. Romantic poets of the nineteenth century wrote of the pallor and near-emaciated thinness of tuberculosis patients, assisting in its fetishization. In today’s world, this is perpetuated by filmmakers and social media. This results in disproportionate representations of the three eating disorders, and creates a toxic ranking based on how nicely they fit into our definition of acceptable female demeanour.

TROY LAWRENCE/ THE VARSITY

Normative femininity

Writers such as Anne Sexton, Emily Dickinson, and Sylvia Plath are just a handful of the many brilliant women in literature who have suffered from disordered eating. As a response to patriarchal constrictions, their confessional writings turned their pain into stories and their psyches into vivid characters.

This brought about curiosity among readers, and created an entirely new genre. Their refusal of food was seen by many as a commitment to femininity, and the documentation of their accounts as products of creative genius. Anorexia reproduces itself in literature as an idolized character of discipline and ideal femininity.

Hollywood today displays vestiges of Victorian standards and Victorian expressions of eating disorders. With films monopolizing eating disorder narratives, we are only hearing a fraction of the story. Where does that leave bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder? Where does it leave those afflicted by eating disorders who don’t fit into the narrow model of an archetypal patient?

Dr. Allan S. Kaplan, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, explains the discrepancy with a general conception of the three eating disorders: “You can characterize the three eating disorders on a continuum of weight. Anorexics by definition are underweight; they have to be. Bulimics almost always are normal weight and it’s hard to know that someone has bulimia; it’s kind of a closeted illness. Binge-eating, because they’re binging and they’re not getting rid of the calories, they’re almost always obese.”

He says, “In our society, and especially the society that young people are drawn to — that can be fashion, modelling, show business — thinness is valued,” but when it comes to other eating disorders, “it’s private, and there’s a lot of shame associated with binge-eating and purging.”

The roots of hierarchy

Among patients, anorexia is often heavily defended as a life choice because it’s predicated on self-control. The ability to restrict is practically sacred, and many will go to great lengths to protect it, whereas bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder are viewed as embarrassing secrets.

“Psychotherapy is important as a cornerstone of treatment but establishing a trusting relationship with somebody with anorexia is not easy… They deny that they have an illness. That’s the first problem. How do you get somebody to engage in the treatment of a condition which they actually deny they have?” says Kaplan of the treatment process.

On the other hand, when it comes to bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder, “a person will come to you and say ‘I can’t stand the binging, it’s driving me crazy. I’ll do anything you want, just help me stop binging.’ It’s a very different mindset and much easier to connect with somebody.”

These illnesses are conceptualized on a spectrum of control replicated in pop culture. Women with bulimia are described as lacking in discipline, a sense of responsibility, and bodily integrity. Bingeing places them in a derogatory light, presenting them as helpless and at the mercy of their compulsions. On the other hand, anorexics have the ‘incredible’ ability to fight impulses. It’s like a superpower. We understand and demonize self-indulgence, but extreme self-control and self-denial? That fascinates us.

What often goes unmentioned is the inevitable psychological and physiological response to the stress of constantly under-eating. After fighting with a deficiency for so long, over half of anorexics find themselves experiencing bulimia and binge-eating disorder somewhere along the way. But this part of the journey is often missing in media. These one-sided narratives skew the reality of the illness, taking out chaos to maintain its ‘clean’ image.

Representations in pop culture

With decades of sweeping the severity of disordered eating under the rug and using it for character idiosyncrasies, this brings about the greater question: is pop culture even the right place for these stories?

“I think what you want to do is portray the illness accurately,” says Kaplan. “Most sufferers are women, but men do get anorexia nervosa. And they tend to be more difficult to treat and they tend to have a poorer outcome.”

Films such as Netflix’s recent To The Bone often place a white, pretty, popular young girl front and centre. Over time, anorexia begins to be mistaken for an exclusive illness. Although young females in Western countries occupy a greater percentage of the diagnostic pool, prevalence rates in non-Western countries have been on the rise, and up to a quarter of eating-disorder sufferers are male.

Men may account for only 10 per cent of eating disorder patients, but the stigma surrounding this condition is far greater for them, which results in many being underdiagnosed and undertreated. They face the challenge of limited resources for recovery, as most are geared toward women.

Men of the LGBTQ+ community were also found to be 10 times more likely to exhibit signs of disordered eating. Transgender individuals in particular are at a greater lifetime risk of developing eating disorders, especially those with low visual gender conformity. Yet these findings remain largely unknown, despite rising prevalence rates in these communities.

A heteronormative and rather misogynistic template exists in this tale. Somehow it became possible to be not white enough, or feminine enough, or straight enough to be taken seriously while having the same illness.

IRIS DENG/ THE VARSITY

Within the transgender community

Only in the last few decades has it become better understood that individuals who experience gender dysphoria are much more vulnerable to mental health issues, and only in recent years have eating disorders in the transgender community been studied critically.

Studies have shown that transgender people are far more dissatisfied with their bodies than cisgender individuals, regarding reproductive body parts or otherwise. A survey of just under 300,000 college students revealed staggering statistics: those who are transgender are four times more likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder, and twice as likely to show symptoms than their cisgender female counterparts. Transgender women tend to share the same reasoning for engaging in restrictive behaviors as cisgender females. Impacted by the same thinness imperative, their habits are used as a means of suppressing masculinity to conform to female beauty ideals.

Much of the existing academic literature on this particular topic has been on transgender women, and the social and cultural parallels drawn to cisgender females. However, a specific case study from 2013 detailed the experiences of an adolescent transgender male who suffered from anorexia nervosa. After his diagnosis, he admitted that he had engaged in restrictive habits to get rid of the feminine features that he disliked on his own body.

Immense body dissatisfaction does not have to be associated with a desire for thinness to manifest in disordered eating patterns. When individuals feel that their own body is foreign to them, they may resort to the most accessible way of modifying their body shape. Those who have yet to undergo hormone therapy or gender reassignment surgery find that their bodies are the primary source of their suffering, and that the misalignment of their sex and gender identity causes them significant distress.

Whose story?

We need to reject false narratives, and we need to tell the whole story. Recognize that maladaptive behaviours don’t discriminate, that anyone can fall victim to them, and that there is nothing poetic or brilliant about eating disorders. Depicting them as such is unethical.

Pervasive shame can result in a fear of stigmatization, preventing bulimia nervosa and binge-eating sufferers from seeking help at all. Anorexia nervosa must be removed from romantic, sexualized contexts to begin deconstructing the hierarchy, and for all eating disorders to be seen as devastating as they are. Currently, these illnesses are organized in a way that is destructive to patient recovery.

Kaplan explains that it’s important to ask about the agenda of media productions for eating disorders. “Is it to portray information accurately or is it to be sensationalistic or to attract attention? That’s two different agendas there,” he says. “It’s more often the latter than the former and it’s a problem because misinformation is portrayed and talked about, then there is often a glamorization and it’s often described as having an achievement.”

Eating disorders are complicated amalgamations of cultural, environmental, and biological factors. “If it was just an issue of being affected by the culture, you’d have way more people than just one per cent of the adult female population evidencing the disorder,” explains Kaplan.

While it may not cause dramatic increases in prevalence rates, communicating the right information is still vital. Poor representation only robs marginalized groups of the attention and resources they need, and glamorization is offensive to the truth of mental health struggles.

We’ve had a long history of getting it all wrong. But that doesn’t mean disordered eating is impossible to talk about. Narratives need be to rid of conditions marking who can or can’t be afflicted by eating disorders. People of colour suffer from eating disorders, and so do men, members of the LGBTQ+ community, and people of all socioeconomic classes and ages.

Hollywood can’t, and shouldn’t be the only setting where conversations about disordered eating take place. As for where discussions on the U of T campus are occurring, Kaplan comments, “I think if it comes from anywhere, it’s often the student body who initiates it. Should the faculty be more aware of it? Absolutely.” Kaplan believes material on disordered eating “should be part of a course in health regardless of what faculty that happens to be in, whether it’s kinesiology, whether it’s medicine, whether it’s psychology… I think there needs to be an increased awareness of these conditions.”

Students and storytellers have the responsibility to search for the right language to discuss this illness, without contributing to the culture that perpetuates it.