U of T’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library houses a collection of rare historical books and artifacts. The collection consists of 740,000 rare books and manuscripts that span nearly 4,000 years of written history.

Opened in 1973, the library first housed the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections and was later named after Thomas Fisher, a merchant miller and community figure in the township of Etobicoke in the mid-nineteenth century.

Fisher’s great-grandchildren donated a generous amount of their collection, including several works by William Shakespeare.

Since then, donations and acquisitions have helped the Fisher Library obtain and maintain important historical documents in varied fields.

Its significant Science and Medicine collection consists of works from the medieval period to the modern age, with ideas that date to ancient Greek and Roman times.

An example of this is an undated Latin manuscript, thought to be from the fourteenth century, of the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid’s Elements. Elements is the earliest written work in the library’s Science collection, and covers theories fundamental to mathematics, particularly geometry.

Alexandra K. Carter, the resident Science and Medicine Librarian, remarked how the introduction of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-fifteenth century might have catalyzed the explosion of scientific ideas.

“Once you could make multiple copies of something, you could have people all over the place reading the same text, and then making similar discoveries,” said Carter.

Within the walls of the Fisher Library are copies of works reflecting the genesis of ideas that are cornerstones of a myriad of scientific and medical fields from anatomy to zoology.

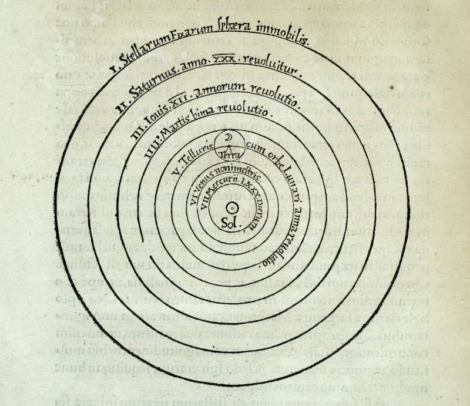

The library’s 1566 edition of Nicolaus Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) presents a heliocentric model of the universe. The library also features titles in the physical sciences, such as Isaac Newton’s 1687 publication of Principia on the Newtonian laws of motion and gravitation, and Antoine Lavoisier’s defining of chemical elements in Traité élémentaire de chimie (Elementary Treatise of Chemistry) from 1789.

Lessons on practical applications for agriculture and horticulture are also available in books such as Jethro Tull’s The Horse-hoeing Husbandry (1829) and Batty Langley’s A sure method of improving estates (1728).

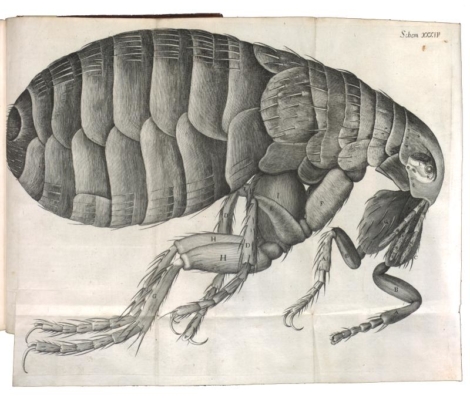

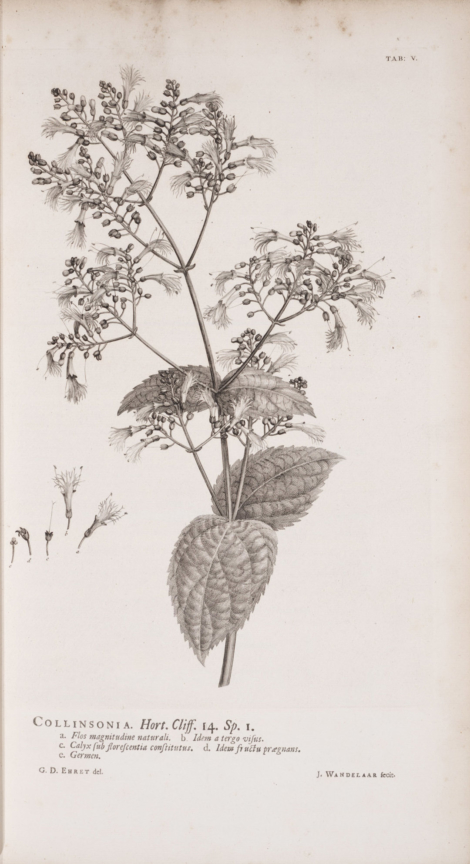

Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665) — noted for the first use of the word ‘cell’ in a biological context — was the first book in English dedicated to presenting organisms and materials as they were seen under a microscope. And in Hortus Cliffortianus (1737), Carl Linnaeus depicted the details of plant species in the botanical gardens of the Hartekamp estate in Holland.

According to Carter, one of the factors that make a title a collectible is scarcity. Older books are prized, especially first editions of historically significant works.

Provenance is also a hallmark of many of the works featured in the Fisher Library. For instance, annotated books by Marshall McLuhan are available at the library. McLuhan was a U of T professor and public intellectual known for his foundational work on media theory in the 1960s, and for predicting elements of the internet well before its genesis.

Unlike other similar libraries or museums that enforce a do-not-touch rule, visitors to the Fisher Library can run their fingers along original writings on major scientific breakthroughs, published on paper that is hundreds of years old.

“We do the best that we can to protect the books, but we really want people to feel that they can come in and use the books,” said Carter, inviting the public to visit the library and experience what it’s like to step back in time and meet the giants of science and medicine.