This is the first part in a three part investigation by The Varsity into Episkopon and the culture of discrimination at Trinity College.

Content warning: mentions of suicide.

Shantel Watson wasn’t sure what was going on when a fellow Trinity College student confronted her for using a communal residence washroom. Watson, then in first year, was stepping out of a shower one morning when the white woman student began to question Watson, as if she was interrogating her for not asking permission to use the shared washroom beforehand.

“It seemed she was trying to police the way I was using the facilities,” Watson said in an interview with The Varsity. Upset over that encounter, Watson remembers leaving the washroom and feeling that someone was watching her.

When she turned around, she noticed the same woman student had followed her out of the washroom and was staring her down as she walked down the narrow hallways of Trinity College. “We locked eyes,” Watson recalled, “and then she jumped back into the washroom.”

Watson left that interaction confused. “I was just thinking why would she think I was [there] to hurt anyone or anything,” she said.

Then the meaning behind the encounter began to sink in.

Beyond microaggressions from teachers or strangers when she was younger, Watson had never experienced anything of that magnitude. She called the experience an “eyeopener.”

Watson, now a third-year student at the University of Toronto, is one of a handful of Black students at Trinity College. According to Trinity College’s 2015 Student Experience Survey, Black students comprise approximately two percent of Trinity’s student body population.

Watson has experienced several other racist encounters at the college since that incident. This past summer, she decided to speak up by writing an op-ed for The Varsity with two fellow Black students that highlighted the impact and extent of anti-Black racism at Trinity College.

In doing this, Watson joins an increasingly large chorus of students and alumni who are coming forward with personal stories of discrimination and exclusion at the predominantly white college, which has a community that some Trinity College students characterize as elitist.

These events led The Varsity to question the larger overall climate of Trinity College and how it is perpetuated at an institutional level.

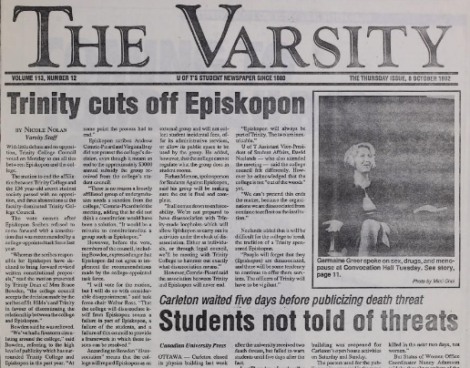

SAMANTHA YAO/THE VARSITY

An institutional reckoning amidst a global movement

Discussions surrounding these issues at Trinity College became heightened this spring following the killing of George Floyd and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. As corporations, organizations, and communities across Canada and around the world began to reckon with and examine systems of racism and discrimination embedded within their social structures, so too did the members of Trinity College.

One June 1, the Trinity College Multicultural Society (TCMS) published a statement on its Facebook page in response to the deaths caused by police brutality and anti-Black racism. The TCMS, created in 2018, aims to “be a space for minority students to seek comfort and support when navigating our educational institutions, which are plagued with systemic racism.”

In the 2023 Facebook group, Black TCMS leaders responded to the statement by coming forward with personal experiences of anti-Black treatment they have received and criticism toward Trinity student leadership’s lack of action towards combating anti-Black racism.

Much of the conversation among Trinity College members in several Facebook groups centred around personal experiences with discrimination at the college or with Episkopon, a quasi-secret society with a history of discriminatory practices with which several Trinity College students are associated — including multiple students in leadership positions.

One of the catalysts that precipitated the vigorous discussions at Trinity College were a series of Facebook posts made in early June by current Trinity College students detailing incidents of racism.

Shortly thereafter, Micah Kalisch, a second-year student, brought the issue of Episkopon to a wider audience by posting a warning in the “Trinity College (UofT) Class of 2024” Facebook group, informing incoming first-year students about Episkopon’s discriminatory nature and actions.

“The group is known for being inherently racist, sexist, classist, homophobic, [and] transphobic,” Kalisch wrote in the post. She went on to share that her message is part of an important movement of dismantling systems within the college that perpetuate anti-Black racism.

The Varsity has tried reaching out to recent members of both the recently dissolved men’s and women’s branches of Episkopon for comment about these allegations of discrimination. They have yet to respond.

“I chose to make that post in the incoming students’ page because when I was a new student, I had never heard of [Episkopon],” Kalisch said in an interview with The Varsity. “It’s important for people to know what this group represents, what this group perpetuates, and what it’s founded on.”

Kalisch’s post — along with other posts about discrimination at the college — started a chain of events that lasted well into the summer and resulted in the resignation of multiple student leaders; an open letter to the college’s administration demanding action on discrimination, which was signed by over 1000 individuals; and a pledge by several student leaders and college administrators to examine and reform multiple systems within the college.

According to a statement by a Trinity College spokesperson in August 2020, they claimed that to their understanding, both the men’s and women’s branches of Episkopon have dissolved. Only the women’s branch has publicly announced their dissolution in June 2020, but The Varsity has been unable to contact the male branch to confirm their dissolution.

These events have been the subject of a three-month long investigation by The Varsity into Episkopon and the culture at Trinity College, including interviews with over a dozen college students, alumni, and administration, along with the analyses of hundreds of pages of documents dating back to the late 19th century.

The findings paint a disturbing picture of multiple forms of institutional discrimination, including racism, elitism, and exclusion, that go beyond the bubble of Episkopon and pervade multiple facets of college and student life. The effects of this discrimination have been perpetuated by the inaction of college administrators and student leaders — a leadership team that, for decades, has had overlapping spheres of influence with members of Episkopon.

Episkopon’s history

For much of its history, Episkopon — or “Pon,” as it has been dubbed by students — was inextricably linked with Trinity College. Established in 1858, the society was described in the 1896 edition of the Trinity University Year Book as a “weapon of righteous indignation, humorous unbraiding or scornful reproval, just and meet.”

Episkopon was, and still is, most well known for its readings — evening gatherings where Episkopon members would recite gossip, often in the form of pointed insults or jokes, aimed at certain members of the community. The jokes and minutes from each reading would be recorded in decorated tomes, most of which are stored in Episkopon’s archives.

Episkopon’s activities, however, did not go unnoticed by other students and the college’s administration, who were often critical of the readings’ content. Several attempts were made to discontinue the activities of the society throughout the first century of its existence, most notably in the 1870s.

First-years in the college pushed back against Episkopon’s repeated criticism of certain students and the derision of their character, leading to the group’s temporary dissolution from 1875 to 1879. Episkopon’s readings were also halted from 1887 to 1888 and once again from 1945 to 1946.

Despite these setbacks, Episkopon continued to thrive throughout the latter half of the 20th century, maintaining its same raison d’être of ridiculing the flaws of other students in the form of jest and insults, all while continuing to receive funding from the Trinity student council as a recognized society.

Episkopon attracted individuals who went on to be recognized members of Canadian society, including luminaries such as former Chief Director of Education of Ontario John G. Althouse, former politician and current Trinity College Chancellor Bill Graham, and former Governor General of Canada Adrienne Clarkson.

It wasn’t until 1992 when Trinity College formally disassociated with Episkopon due to allegations that the group harassed students on the basis of race, gender, and sexual orientation.

This was preceded by a string of serious incidents from the mid-1980s to early-1990s, and students threatened a lawsuit against the university if Trinity College failed to disassociate from Episkopon.

A year prior to the college severing all official ties with the group, a student targeted by Episkopon threatened to take their own life, while another student who was critical of the society had a bucket of human feces and urine dumped in their room, as was reported by The Varsity in 1992.

In spite of these incidents, there was considerable pushback from members of Trinity College — including students in leadership positions — against Episkopon’s removal from the college.

Episkopon today

Today, Episkopon remains officially disassociated with the college. Yet, since 2017, there has been a steady presence of several Episkopon members serving as elected officials for Trinity College each year. In addition, the three yearly readings — which are typically held at a variety of locations throughout the city, including Trinity Bellwoods Park — are well attended by non-members such as first-year students at Trinity College and, at times, alumni.

The most distinctive structural aspect of Episkopon is its gendered nature, with the organization being split into two groups — that of men students, “Man-pon,” and that of women students, “Fem-pon.” A scribe functions as the head of each of these two branches, and each head is supported by two senior editors. Every other member who is initiated into the society is an editor.

Victoria Reedman, an alum of Trinity College and a former Episkopon member, recalls her responsibilities as a member of Episkopon with aversion.

“It’s very Mean Girls,” she said. “When I was a part of the organization, a lot of it made me really uncomfortable. I didn’t like writing the jokes, and I wasn’t very good at it. And I especially didn’t like writing jokes about other people.”

Throughout the year, editors are responsible for updating a list, known among members as the “Shit List,” on a running Google Doc. It is part of their role to keep an eye and ear out for gossip circulating through the college and any drama that might be worth broadcasting at the readings.

Joke writing is also done in a gendered manner. Women editors are responsible for writing jokes about women members of the college, while men editors are responsible for writing jokes about men members.

Students may request not to be mentioned in the readings. But rather than an opt-in process, students must approach an Episkopon member in order to opt out. And sometimes, even this request is denied.

Readings cover a wide range of topics and have even been known to target particular individuals for their sexual history, according to two former members. Scribes would denigrate women students for being virgins or would call them out for being too sexually active. In addition, the men’s branch of Episkopon would often craft sexist jokes that conveyed that women’s jokes are inferior to men’s.

Andrew Ilkay, a Black Trinity alum and a former member of Episkopon, highlights how fellow members would don a “progressive” mask in their everyday lives yet act far differently behind closed doors at Episkopon gatherings. “There was a general fake progressiveness that we kind of felt we embodied,” he shared. “But in practice, we probably didn’t embody it.”

Trinity College’s Episkopon Policy has a negligible impact

Since 2010, all incoming students are made to sign Trinity College’s Episkopon Policy. By signing it, students agree to refrain from organizing, participating, or publicizing any Episkopon-related events on college property or in connection with college events, and obtaining funding from Trinity College to support Episkopon events.

However, The Varsity’s investigation reveals that few students pay much attention to the beginning of year forms that they are supposed to sign, including the Episkopon Policy. In addition, the rules are rarely enforced and often broken.

For many first-years, their first introduction to Episkopon is through interactions with upper-year students. New students may hear about it during frosh week at the start of the school year, when orientation leaders affiliated with Episkopon would coax unsuspecting first-year students to attend the first reading by advertising it as a college-sanctioned ‘ice cream social.’

Episkopon’s open readings are also promoted over Facebook and informally spread through word of mouth throughout the college. Others may receive an innocuous card under their residence dorm door, telling them to meet at a particular location off Trinity College property.

Perhaps the most brazen form of recruitment, however, is when Episkopon members, dressed in their distinctive black robes and holding candles, promote readings at the end of college-sanctioned frosh activities — “purposefully fitted into the schedule” by the student heads, according to former Student Head David Ingalls in a Facebook post to a private group for Trinity College students. Ingalls resigned this past summer.

The Varsity has also tried reaching out to recent members of both the men’s and women’s branches of Episkopon for comment on the allegations that they continued to promote their group against Trinity policy, but they have not responded.

For the 2020 orientation event, there were several students affiliated with Episkopon who were sitting on the orientation planning committee or going to be student leaders for the weeklong event.

In a letter obtained by The Varsity addressed by the Dean of Students Kristen Moore to the orientation week leaders, the college requested students with prior involvement with Episkopon to step down from their orientation week position in early July.

“It would be inconsistent with College policy for us to permit students who have had involvement with Episkopon to hold such a crucial role in welcoming and introducing our new students to life at the College,” the letter read. “As such, we are requesting that you reflect inward, and make an assessment as to whether or not you have a current or former affiliation with Episkopon.”

Since the resignations were based on an honour system, it is unknown if there are currently any members of the orientation week team that hold current or former affiliations with Episkopon.

When Watson was in her first year, she and her friends were approached by a man frosh leader, who openly declared his Episkopon membership before trying to dispel the negative commentary surrounding the society. “To speak about Episkopon in that manner was definitely inappropriate,” she reflected. “His response should have been that Trinity does not promote or associate itself with Episkopon.”

No matter the method of recruitment, for many first-year students, the Episkopon described to them during the first weeks of school is far different from the real Episkopon. The Varsity investigated the past and present allegations against this group that is both shrouded in misinformation and secrecy, and occupies a major space of the social scene for Trinity College students.