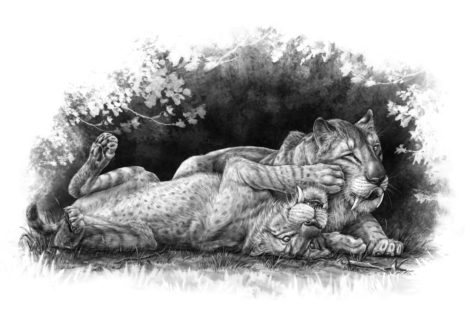

Recently, U of T researchers working at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) were working on cataloguing fossils of a prehistoric big cat when they discovered that their fossils were of a mother cat and two adolescent cats. These fossils of Smilodon fatalis — also known as the sabre-toothed cat — were proof that prehistoric big cats cared for their young for as long as some modern-day cats do.

The key finding was that, like lions, these cubs often stayed with their mothers for at least two years, but unlike lions, they were nearly fully grown by then.

The sabre-toothed cat

Smilodon fatalis was an apex predator, weighing in at over 600 pounds with seven-inch-long canines. They ranged over what is now North America until around 10,000 years ago and are sometimes incorrectly referred to as sabre-toothed tigers, despite being only distantly related to the modern tiger species.

In 1961, a set of Smilodon fatalis fossils were brought to the ROM from Ecuador. The fact that the fossils were all found together indicates that the animals died suddenly, possibly from a flood.

Ashley Reynolds, a PhD candidate in the Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, was cataloguing these fossil specimens when she noticed that three of them shared a set of rare dental features. This was a clue that they might be related.

A long adolescence

In fact, analysis showed that two of the cats were siblings, young juveniles no more than two years old, and that the third fossil was likely their mother.

Among modern cats, lions are known to stay with their mothers for up to two years. Tigers, meanwhile, are independent by then, partly due to their rapid growth. These fossils were both approaching maturity and found near their mother.

This implies that sabre-toothed cats had a life cycle combining elements from both lions and tigers. “It grew quickly, like a tiger, but they probably stayed reliant on their mother for a long time, similar to a lion,” Reynolds wrote on Twitter.

This finding is part of a growing body of research shedding new light on an already well-understood animal. Once imagined as a free-roaming hunter like the modern lion, more recent dental analysis of Smilodon fatalis fossils suggests that the cats were forest dwellers, specialized in hunting smaller animals.

In 2019, Reynolds led a team that discovered the first Smilodon fatalis fossil in Canada in southern Alberta, pushing the boundaries of where the big cats roamed about 965 kilometres north of the previous estimate.

“For me, I always thought fossils were interesting, but I didn’t think that I would end up studying them until I was toward the end of my undergraduate degree,” Reynolds wrote in an email to The Varsity.

“What I love most about being a palaeontologist is the unique way we have to think about the animals we study. Because we can’t observe extinct species in the wild, we need to get creative with how we approach questions that would be relatively easy to answer for a living animal.”

When asked why her research focused on big cats specifically, Reynolds said their unique dental structure was part of what makes them so interesting. Cats are obligate carnivores, meaning that they solely consume meat for their diet.

“While most carnivorous species still have teeth capable of processing other types of food, all the teeth a cat has are optimized for hunting and slicing meat,” Reynolds wrote.

But she also responded in a way that cat owners can relate to even if they are not palaeontologists themselves: “Well, cats are simply the best!”