The early careers of analysts in fields such as finance, consulting, and investment banking are notorious for long hours, with analysts sometimes clocking a whopping 60 to 100 hours a week. These positions are also known for paying high salaries and providing promising career growth opportunities, but is the trade-off of a poor work-life balance and handsome compensation really worth it?

Happy analysts

Professor Ole-Kristian Hope, the Deloitte Professor of Accounting at the Rotman School, is one of the authors of the study Happy Analysts, which analyzes the optimal work-life balance for entry-level financial analysts. The novel study is among one of the first papers to analyze the impact of work-life balance on employee performance.

In an email to The Varsity, Hope explained that several factors led him to pursue this study, such as his prior research on analysts and a desire to study work-life balance more broadly. “No prior research had access to such detailed data as we have in our study (from Glassdoor). Most prior research has focused on a particular company (a ‘case study’) while we provide large-scale empirical evidence,” he wrote. The authors of this study have used 6,192 samples from Glassdoor to perform their analysis.

The study was co-authored with Congcong Li of Duquesne University, An-Ping Lin of Singapore Management University, and MaryJane Rabier of Washington University in St. Louis. It was published in a recent issue of Accounting, Organizations and Society.

A non-linear relationship

After examining a large sample of employee reviews on Glassdoor — a website where employees anonymously review the companies that they work for, or have worked for in the past — Hope and his colleagues found a non-linear relationship between work-life balance and analyst performance and career advancement.

When the perceived level of work-life balance is low, meaning analysts perceive that they spend the majority of their time working, increases in work-life balance yield positive results in terms of better analyst performance and career advancement. On the other hand, when analysts’ perceived level of work-life balance is high, meaning an analyst perceives that they have enough time outside of work, reducing work hours yields negative results, and is usually associated with worse analyst performance and career advancement. This is because employees need a certain level of psychological stimulation to function efficiently.

The study sought to determine the optimal level of work-life balance that made analysts the most productive and efficient by taking forecasts that an analyst had done on a company’s future earnings while also rating their work-life balance level on a scale from one to five. The study found that on average, analysts’ forecast accuracy — how correct their forecasts are about a company’s future earnings — reaches the highest level when their perceived work-life balance has been rated at 3.47 out of five.

Striking that balance

Hope found that the practice of supporting employees in terms of work-life balance varies greatly between each sector and country.

He noted that North America is not as good in providing work life balance for employees in comparison to other nations, such as Europe. North American companies offer less vacation and limited leaves while the focus on work-life balance is more prominent in Europe.

“I believe improving [work-life balance] can be a competitive advantage for firms in attracting and retaining high-quality employees,” wrote Hope.

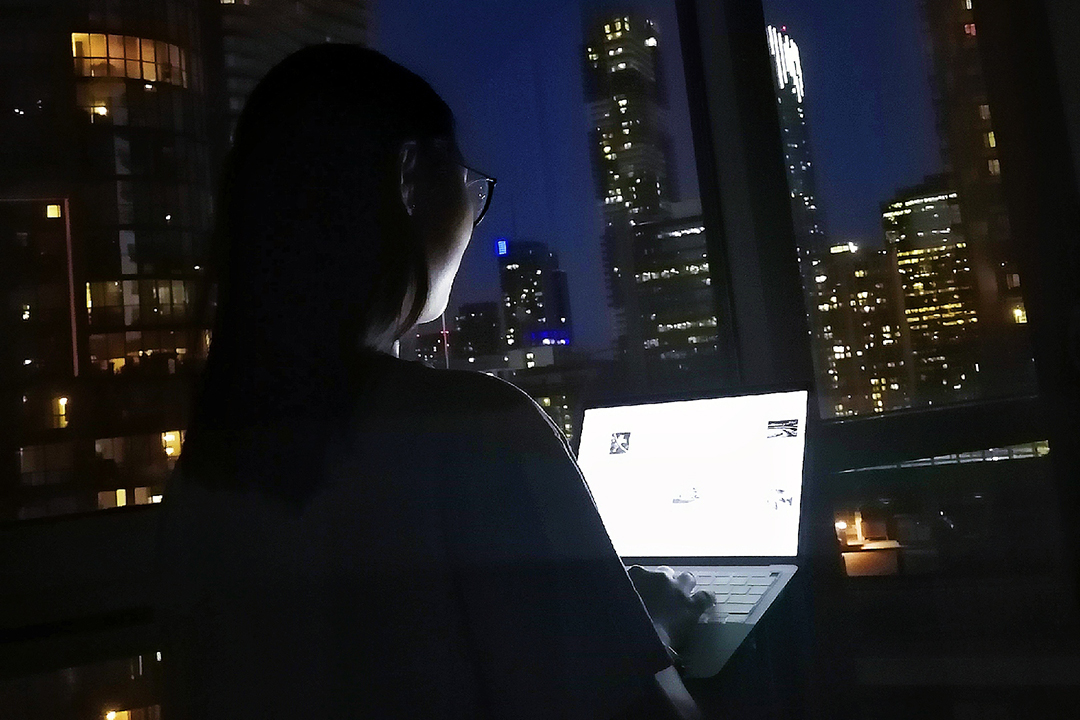

Katherine Ye, a fourth-year economics student, is currently a finance intern at Thomson Reuters. The company offers mental health days, autonomy on projects, and networking opportunities. Ye has been enjoying her experience and feels lucky to have a healthy work-life balance. However, working from home can blur the lines between when she is working and when she’s not working.

“I’ve noticed that many of my colleagues don’t log off for lunch and remain at their desks to eat. Seeing the yellow ‘away’ symbol next to my icon on Microsoft Teams makes me nervous because, as an intern, I want to show that I’m as present as possible,” she wrote in an email to The Varsity.

Hope believes that some work-life balance is good for all employees and can take many forms in their lives such as staying active, pursuing hobbies, and spending time with friends and family.

Hope offered similar advice to undergraduate students. “You should study hard but also strive to be well-rounded individuals — this will improve overall health and well-being and likely also lead to greater academic and career success.”