Belfast is the most recently premiered film from Sir Kenneth Branagh, a British writer, director, and actor whose career spans for decades. In a hit-or-miss filmography, the semi-autobiographical film stands out by marrying Branagh’s signature sentimentality and charm to an uncharacteristically personal story.

Branagh is a classically trained actor, best known for his English-class staple Shakespeare adaptations, spins on classics such as Frankenstein, and oddly dispassionate studio tentpoles. His films usually carry a sense of grandiose theatricality and melodrama, where human emotion is magnified and visualized into an electric and abrasive style via crashing lightning, eccentric angles, or exaggerated acting.

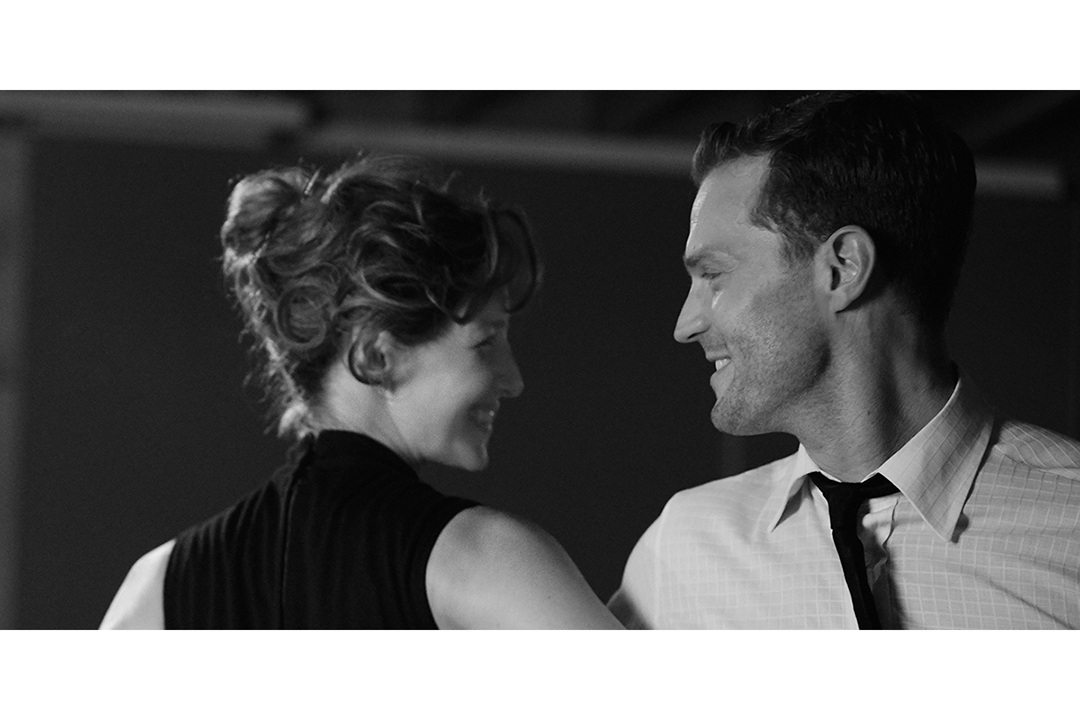

Leaning away from these impulses, Belfast is surprisingly subtle and tender. The film reflects on Branagh’s childhood growing up in Belfast, Northern Ireland, during the late 1960s. We see it through the eyes of nine-year-old Buddy — portrayed by Jude Hill — who’s the centre of an impressive ensemble cast. Buddy traverses the tumult of religion, romance, and family drama as anti-Catholic riots escalate in his beloved, tight-knit community. With the situation becoming increasingly perilous, his parents — moving performances from Caitríona Balfe and Jamie Dornan — are forced to decide whether or not to leave what has been their generational home.

The film is clearly an exercise in nostalgia and acts as a sort of dramatized memoir. Its reality remains somewhat heightened and fantastical, though mostly through tone and atmosphere. Everything is defined by Buddy’s perspective, and further what Branagh’s consciously rose-tinted memories refine the child’s view to.

Belfast is shot in deep black and white and largely confined to a single block. Belfast is his world. Most of his life takes place on one street, where everyone is friendly and knows each other — trouble and disharmony only ever come from the outside. His family consists of simply “Ma” and “Pa” and “Granny” and “Pop.” Belfast, both the film and the city, is emblematic of a time in Branagh’s life that felt happy and simple, despite the chaos and violence embedded throughout.

Any main plot feels secondary to bearing witness to life, like a bittersweet reminiscence. The lack of direct narrative thrust does sometimes leave the movie in awkward places. The script is excellent on a moment-to-moment scale, which is how most of Belfast operates. Its charm and heart are strong, but it doesn’t feel like a single piece. The transitions between what feels like disconnected vignettes interrupt the film’s sensitive pace and flow. After a great visual tour of Belfast, its connective tissue feels like objects of necessity rather than of specific purpose.

The most traditional arcs — mainly concerning Buddy’s semi-absent father’s struggle with the Protestant radicals fracturing the neighbourhood — don’t feel innovative. Buddy’s family conversations are heartwarming and melancholic, due to terrific performances across the board, but there’s not a whole lot more to the story outside what you might take from its face value.

However, given the backdrop of Buddy’s passion for film and theatre, words and deeds assume more meaning. The movie is entirely cast in his dramatizing instincts; equating his father with a heroic Western sheriff, for example. We see and feel the world of the film through Buddy: his fear through the booming voice of a pastor, and his joy as he watches films with his family, whose vibrant colours invoke wonder and inspiration against the generally monochromatic scenes. It’s an unexpected and smart touch.

Visually, Belfast feels scaled back from Branagh’s other works that are more stylistically intense — like in Thor, where basically every other shot is on a 45 degree angle. Instead, it relies on simple camera movements and steady, stark compositions. The characters take centre stage rather than occupying the space within a slick maneuver of the camera.

The black and white cinematography by one of Branagh’s regular collaborators, Haris Zambarloukos, creates a mixed effect. On a thematic and atmospheric level, the look contains tactful touches of colour, solidifying its intentions. Many modern implementations of black and white, especially amateur ones, fall into a muddy digital look that bury important details in dull shades of grey. Belfast occasionally stuns with harsh contrast and striking framing, but it just as often ends up looking disappointingly flat.

Still, Branagh’s film is a delight to watch. Even his most serious and action-packed projects have a soft, sentimental edge to them, and Belfast uses it in a new way. The joy, love, and goodness that binds Buddy’s life together brings out a longing for times past, regardless of one’s specific origins. By placing us so tenderly in his own shoes, Branagh makes his individual story universal.