Given the unprecedented success of the People’s Party of Canada (PPC) — Canada’s most right-wing party — in the recent federal election, it’s understandable why many Canadians are speculating whether our politics are shifting rightward.

Although the PPC has yet to win a seat, the party — whose platform focused on opposing masks and proof of vaccination mandates — saw its numbers increase by 1.6 per cent since the 2019 election. In fact, this year, the PPC received 4.9 per cent of the popular vote — 2.6 per cent more than the Green Party. The growing success of the PPC is fueling fears of rising right-wing extremism in Canada. However, this growing fear may not be substantiated, and can instead be attributed to COVID-19.

Vote splitting at its finest

Canada’s political landscape consists of six main federal parties: the Liberal party, the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC), the New Democratic Party (NDP), the Bloc Québécois, the PPC, and the Green Party of Canada. All of these parties, except for the CPC and PPC, can be categorized as left-leaning, representing various levels of liberalism.

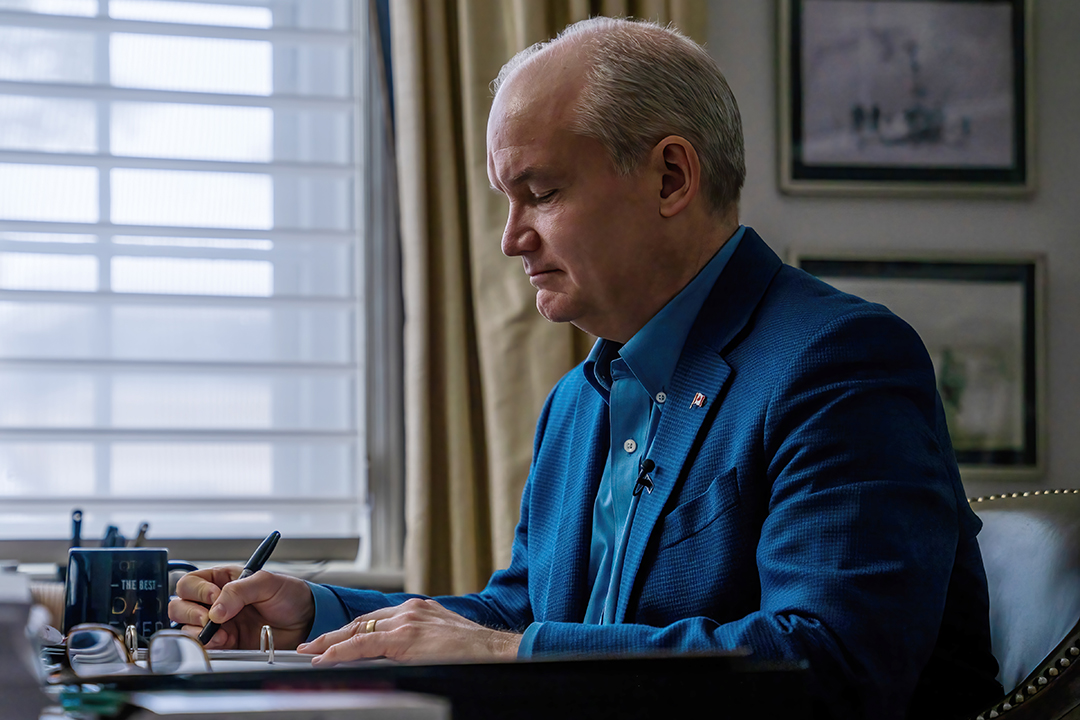

Interestingly, under the leadership of Erin O’Toole, the CPC has made a shift back to its centrist roots instead of leaning into Harper-era conservatism. This decision was made with the idea of attracting more voters from the left, providing the CPC with a better chance of winning future elections — a strategy that has been ineffective, given its latest loss to the Liberals.

In recent pre-PPC elections, right-wing voters only had one option: the CPC. Therefore, we see that it’s not that PPC voters didnʼt exist before; it’s just that there wasn’t a party catering toward their specific level of conservatism, so they settled on the next best option.

Since the CPC has decreased its level of political polarization, and there is another option available to voters, it’s only logical that we see a rise in the PPC’s numbers. This means the assumption that Canada is becoming more right-wing isn’t likely to be true.

The dangers of populism

Robert Bothwell, a professor of international relations at U of T, wrote a warning about dismissing groups like the PPC too quickly in an email to The Varsity. “We tend to think that [PPC] supporters — actual or potential — are rubes based in the backwoods. Some are, just by the law of averages but I have to bear in mind our local experience with Mayor Rob Ford in Toronto. He was, in my opinion, publicly and obviously unfit for office and made Toronto an international laughingstock.”

Bothwell expressed shock at how educated and wealthy people, including those with U of T degrees, could support Ford. He attributed this wide reach of support to Ford’s populist platform. “Under some circumstances, as yet unknown, populists can expand beyond what we think of as their usual base,” Bothwell wrote.

Therefore, although we can attribute the PPC rise to the centrist push by the Conservatives, there is a great deal to be said about the implications of the PPC’s platform. In light of its fight against a government backing COVID-19 health and safety measures, the PPC emerges as a rather populist party that provides the illusion of “the people fighting back against a broken system.”

As a result, many have chosen to not take the PPC seriously. However, as we’ve seen with Ford, this kind of emotional call to action has proven dangerously effective, which we must be mindful of.

The future of the CPC

Consequently, the Conservatives are now faced with a dilemma: either they can continue trying to modernize the partyʼs views in hopes of winning over more voters from the left, or they can revert to their past ideology and risk losing younger generation voters — including U of T students.

Bothwell highlighted this dichotomy, writing, “The trick is that in our divided party structure and first past the post elections it only takes 35 per cent of the votes to win a majority, if you’re lucky… So if your base is, say, 30 per cent you only need to add a few points. Look at the recent election. An appeal to the base only is thus not totally irrational. [O’Toole] was trying to take the federal party back some distance in time, but it was a time in the memory of many— pre-1993 — when the Tory party was less ideological and frankly more successful.”

Therefore, for the CPC, which already holds a large base percentage, a platform that focuses on centrism could be the secret to winning an election. By being less ideological, it can appeal to a greater number of people — voters who would otherwise be voting for the left. Although this centrist strategy failed to succeed in this year’s election, the extenuating circumstances of COVID-19 make it difficult to accurately assess the strength of the strategy based on these results alone.

Bothwell suggested taking a look at the past to see how this would look. Former Progressive Conservative (PC) Prime Minister Brian Mulroney perfectly embodied this centrist approach — a strategy that won him back-to-back elections, making Canadian history with the most seats ever won.

Ramifications for students

A more right-wing conservative government would have a vast number of ramifications that would be felt by U of T students. Even at its current level of polarization, the PPC ran a platform eliminating all government subsidies to businesses. This anti-government-involvement, cost-cutting rhetoric could be intensified if the party shifts further to the right.

In the recent election, the Liberals ran a platform that would increase the minimum income required to start paying back loans, create new jobs for students, and plan for eliminating federal interest on Canada Student Loans. On the other hand, the CPC proposed some tax breaks for graduate students but failed to include any of them in their running platform. With a move to the right, one can imagine how much worse these student benefits would get.

Overall, it’s safe to say that Canada isn’t experiencing a rightward shift; rather, we’re observing a group of individuals that finally have a party to vote for that embodies their ideologies. Nevertheless, seeing how the CPC and other voters will react to this increase in support will define Canadian politics to come.

Nina Uzunović is a first-year social sciences student at Trinity College.