At some point in our lives, we’ve all been presented with the internal conflict: do I identify more with the arts or sciences?

U of T student Sana Khan is combining her love for both. As a medical and scientific illustrator, Khan uses anatomy sketches, animation, and 3D technology to present complex diagrams to people without a scientific background. However, Khan is also leaning into her artistic side by selling her pieces as decorative works on her Etsy shop.

The Varsity interviewed Khan to discuss her artistic training, her career, and her opinion on the divide between art and science.

The Varsity: What do medical and scientific illustrators do?

Sana Khan: Our main job is to basically translate complex scientific information into a visual form so that it’s easier to understand. This is especially important in this day and age, when all this complex research is coming out but then there’s no way to convey it to the public. It’s our job to fill in the gap between science and the public.

TV: How did you get into medical and scientific illustrating?

SK: I’ve been making art for as long as I can remember. In middle school, I would participate in art clubs and art contests. During my undergrad, I stopped for a bit to focus on the science side, so I did my specialist in neuroscience at UTM, and then I found out about [U of T’s Masters program in biomedical communications] that merged the art and the science together.

TV: How did you learn to make sketches? Did you take any kind of formal or informal education, certifications, or classes?

SK: I was able to learn how to draw but I had no formal education, so I guess I would say I’m self-taught, because it just came with a lot of practice. I’m a very detail-oriented person and a perfectionist, so when I’m creating my drawings, I pay a lot of attention to detail and that takes a ton of patience — something I’m still learning how to do. I think observational drawing really helped me a lot because I would sit down and draw whatever was in front of me, and that’s how you get better at it.

TV: Is making these illustrations a hobby for you or more of a career?

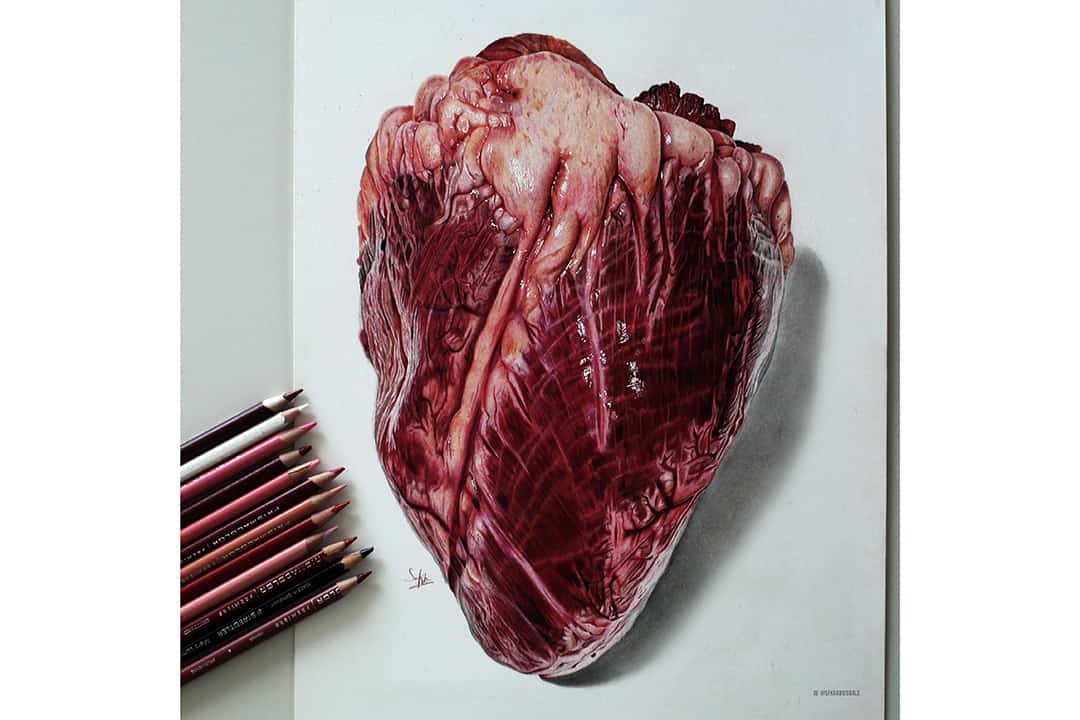

SK: I have an Etsy store where I sell anatomy prints and drawings I made as part of my coursework. Some of them I made just for fun, and that part is more of a luxury. People buy that and hang it up and it’s just nice to look at. But then there’s the whole field of medical illustration and animation where you design visuals for textbooks, companies, for hospitals, or for patient education, and that’s what I would say where my career is.

TV: What’s your creative process like when you’re starting to sketch?

SK: The first stage would be the research stage, where I would gather all my visual references, especially if I’m drawing something hyperrealistic. When you’re doing hyperrealistic art, you have to pay attention to a lot of detail, which requires a lot of references.

If I’m designing an infographic for something space-related, I’d have to do all the science-related research about space, and then I would have to do the visual research. So gathering other space infographics and seeing what the artists came up with is more science-oriented than the stuff that I produce for the actual field, rather than just my coursework.

TV: How do you think technology intersects with this art and the field of scientific illustration as a whole?

SK: I would say it’s very tech-heavy. As of maybe ten years ago, there’s a huge focus on 3D animation and replicating the real life mechanisms of our bodies and molecules. There’s a lot of digital drawing. I wouldn’t say traditional art is dying. It’s still part of the process, especially the preliminary phase when you’re starting to sketch out your ideas.

TV: How do you think that the field of scientific illustrators bridges the age-old ‘art or science’ debate?

SK: There are people who always try to identify themselves as more artistically inclined versus more analytically inclined; the field that I’m in merges both of them. If I’m drawing from a reference, I have to learn to break down that reference into pieces. Even though the final result that you produce is very different, the process in order to get to that final stage is very similar.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.