In his inaugural speech as the chair of the Universities Canada board, U of T President Meric Gertler emphasized that universities have an important place on a global scale, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. He positioned the University of Toronto as a community leader, saying, “Many of us have pioneered vaccine mandates, the safe return to congregate living and assembling indoors in higher densities — well before other sectors have followed suit.” Gertler projected universities as forward-thinking microcosms of reality that can create local and global innovation.

From an academic perspective, it is obvious that universities have a great importance on a global scale. They are places where bright and curious minds gather to discuss, offer new insights, and, in some cases, solve problems. For instance, at U of T, scientist Frederick Banting and his student assistant Charles Best discovered insulin 100 years ago.

Universities can also have a global impact beyond academic research, through their youngest and most energetic assets: students. Through their students, universities play an important role in training the next generation of global citizens that will rise to challenges around the globe.

According to Oxfam, a global citizen is “someone who is aware of and understands the wider world — and their place in it.” Being a global citizen also means engaging in a transnational way of thinking — a way that goes beyond the walls of the university and beyond Canada’s national borders.

Universities like U of T are places where students can discuss ideas with other bright students — often from diverse backgrounds — and gain different points of view. As U of T Vice-President International Joseph Wong told U of T News, “It’s one thing to read about nationalist movements in Europe or South Asia… It’s an entirely different learning experience when you can talk to — and learn from — your peers who are from these regions.”

Thus, at U of T and other universities with many international students, diverse perspectives are readily available, and one doesn’t need to travel far or use Google to access important and valuable information. The distance needed for transnational discussion decreases at multicultural universities such as U of T, allowing for localized transnationalism to occur. Even the city of Toronto itself has a multicultural population, meaning that Toronto can be considered, to some extent, a microcosm of the ‘global village,’ a term coined by Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan in 1960.

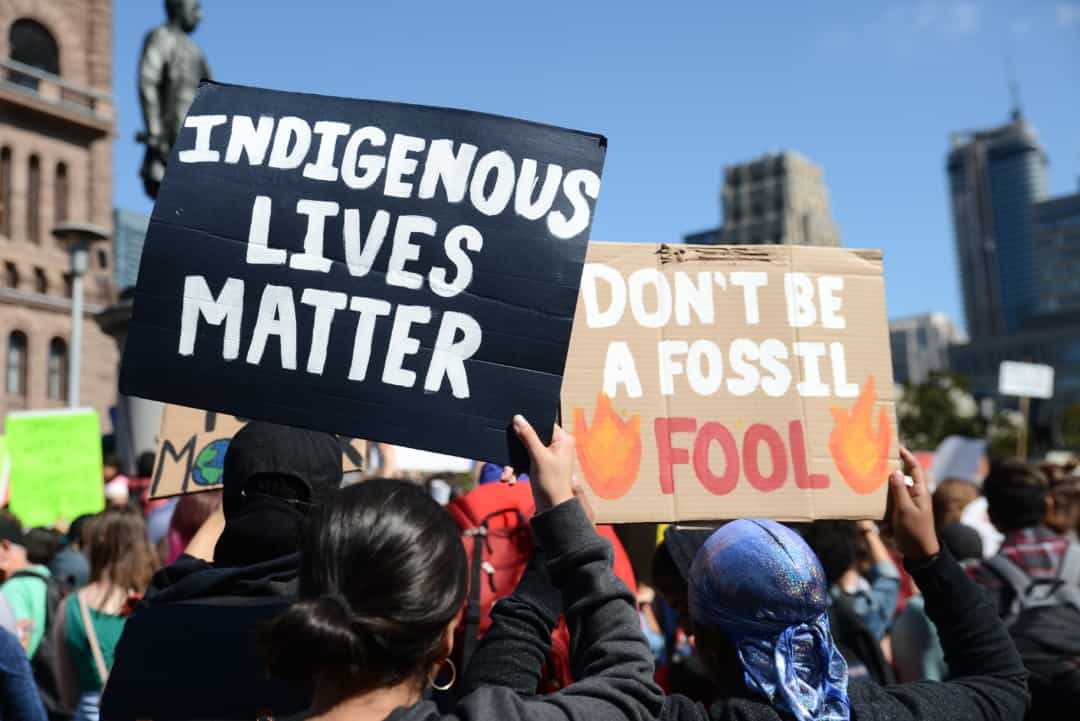

A transnational approach to learning about the world can ignite passion within students for salient and international issues such as the climate crisis. Alienor Rougeot-Maroniez, an organizer at Fridays For Future Toronto, has previously told U of T News about how her time at the University of Toronto inspired her to take action.

In her case, the transnational nature of the curriculum and conversation may have been factors in her involvement with the climate movement. And mass organizing by both students and faculty has paved the way for a greener University of Toronto: the university recently announced its plans to divest from fossil fuel companies by 2030 and to commit to net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Universities fostering places of global citizenship does have implications for marginalized students who may find it difficult to enrol and remain in university. If universities create global citizens, then are universities also unwittingly creating a case of global ‘sub-citizens’ who possess fewer benefits and opportunities? Perhaps — but that question will require more thought, attention, and research.

Nevertheless, global citizenship has become increasingly important due to the emergence of a very pressing global challenge: COVID-19. Beyond getting our own communities vaccinated, vaccines have to be urgently distributed to lower-income nations for the pandemic to end globally.

However, there have been issues in distributing enough vaccines. COVAX is an initiative seeking to quickly develop and manufacture vaccines for equitable distribution to every country. However, the People’s Vaccine report “Dose of reality” details how the four leading vaccine manufacturers — Pfizer-BioNTech, Johnson and Johnson, Moderna, and AstraZeneca — did not provide half of the vaccines they had promised to COVAX in 2021.

According to the United Nations, “inequitable vaccine distribution is not only leaving millions or billions of people vulnerable to the deadly virus, it is also allowing even more deadly variants to emerge and spread across the globe.” This process only works to exacerbate the economic polarization between the high-income and low-income nations. As the world battles this pandemic, it is imperative U of T’s scholars coalesce to urge the Canadian government to act on global vaccine inequality. The academic diversity of U of T’s student body lends itself well to the fight against vaccine inequality, and both students and faculty can gather for advocacy and awareness purposes.

In the face of the pandemic, U of T owes the world not only well-informed students, but also continuous innovation and spaces where scientific dialogue can reimagine an optimized future beyond COVID-19.

Joël Ndongmi is a third-year political science student at Victoria College.