Content warning: This article discusses police violence against Black people and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is not the first conflict that has occurred since social media established itself as a platform of change. However, this war is one of the first international conflicts to receive as much attention as it has gotten over the past few weeks.

In light of current issues on social media — including the coverage and activism surrounding Black Lives Matter and Israeli aggression toward Palestinians this past summer — three contributors reflect on what it means to be an activist on social media, and discuss common pitfalls that people fall into when raising awareness for a particular cause.

Performative activism is no substitution for action

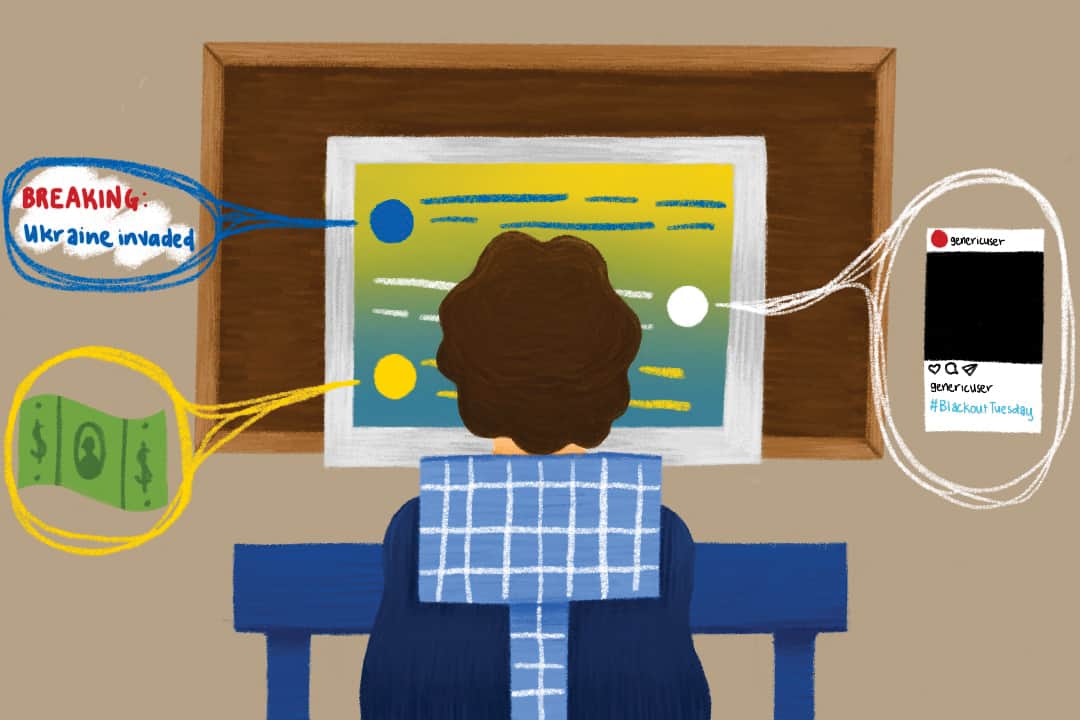

When mainstream media reports on police brutality within and across our borders, the casualties of violence in the Middle East, and the recent invasion of Ukraine, we may feel hopeless. Social media offers us a platform to share our opinions — to feel as if we are a part of the effort against global injustice. Yet performative activism has corrupted this effort.

Performative activism involves projecting a positive self-image online in order to prove that one stands with a given cause. Performative activism arises when people post about an issue not to inform others, or because they care, but because they fear that others will think they are on the ‘wrong side.’

Online posts about current events have transformed from demonstrations of solidarity into moral performances that inspire the condemnation of people who have not yet shared that they care and that they stand with social media activists. You see a post of a flag and think, “Good. They’re with us.” But how does that post improve the lives of all the people that flag represents? A social media post is no substitution for action.

Online activism is not inherently corrupt, but the culture of denouncing someone who doesn’t publicly share their stance does diminish the meaning behind a post. A consequence of this culture is that it commodifies victims of violence and renders them into moral chips. While a picture of a Ukrainian child fleeing their home is indeed meaningful, it is immoral to use this child to prove to an Instagram following of 900 people that one is against the ongoing war — there are more meaningful ways to do that.

If someone does not post about the Israel-Palestine issue, does that mean they do not know it is happening? If someone does not tell you that bombing Ukrainian cities is deplorable, do they side with Putin?

Ask yourself whether you posted a black square and captioned it #blackouttuesday after George Floyd was killed in May 2020. That square didn’t help anyone. What that square achieved was the interruption of news outlets trying to spread word of a man being murdered because he was Black.

Sarah Stern is a second-year English student at Victoria College.

Reductionism discourages us from nuanced thought

Social media advocacy often treads into waters that are dangerous, and many people don’t seem to notice. The biggest problem, at least in my opinion, is the normalization of reductionism and oversimplification.

To me, there’s a clear pipeline for people on social media recently. Social media users consume reductionist and ‘digestible’ content, often associated with groups with clear ideological biases, and do not look any deeper into the nuances of the topic.

This happens now with many, if not most, controversies on social media. Social media advocacy, without fail, seems to devolve into delusions that warp the actual situation to make it less complex. For example, a Canada Day post by the very harmful Instagram account Impact insinuated that everyone who celebrates Canada Day “celebrates colonization, cultural genocide, and abuse against Indigenous people,” which is neither helpful nor accurate.

This statement effectively shames Canadians not just for celebrating Canada Day but, in reality, shames them simply for being Canadian. What does this post contribute other than the ever-so-popular ideological self-flagellation that holds no purpose whatsoever? It doesn’t provide any real change for Indigenous communities, nor does it in any way help reconciliation.

The current war in Ukraine has also prompted fast, reductionist ‘takes’ on social media that can spiral into full-on propaganda. Comparisons between Ukraine and other wars or struggles, for example, are very popular but widely unhelpful.

One post I found compares the Palestinian struggle against the Israeli state and the sudden, unprovoked Russian invasion of Ukraine, which are completely different. The comparison post — perhaps unintentionally — helps Russia by deflecting from the atrocities happening in Ukraine. The post also implies that the world wasn’t paying attention to Palestine — but there was wide outrage over the Sheikh Jarrah evictions through late 2021 and into early 2022, so this post’s premise is also not based in fact.

These are two tamer posts, purposefully chosen to limit the spread of disinformation. Now, I’m left here asking this: how are posts like these helpful? Sure, these topics are important, relevant, and should be talked about — but how do social media posts about them contribute to achieving justice? The answer is that they don’t: they oversimplify, and often, they harm the cause they’re advocating for.

Social media advocacy is not only one of the most ineffective ways to effect change but it is also one of the most dangerous ones. What I’ve just described can lead — and has already led — to a growing mob mentality and rampant spread of hatred and misinformation. We have to stop this cycle of consuming social media without investigating the issues further. It’s only resulting in oversimplified, reductionist, harmful content that translates into reductionist, harmful rhetoric in the real world.

Logan Liut is a first-year social sciences student at University College.

Put your money where your mouth is

Performative activism is only effective when it is backed by material resources. Unfortunately, ‘thoughts and prayers’ do not count as material.

I do personally sympathize with those who are engaging in performative activism. In May 2020, when the Black Lives Matter movement experienced a resurgence after George Floyd’s murder, I remember posting a series of photos on my story, listing names of young Black men who had been murdered. Reflecting on it, I believe that my intentions were pure — as I am sure most other performative activists believe about themselves.

However, my quest to educate my peers about the atrocities against Black people throughout US history had already been achieved by the many accounts doing the exact same thing. Moreover, my followers consisted of my friend group, and the vast majority of them seem to share the same liberal political stance. I lectured into my social echo chamber, verifying that all my friends supported Black Lives Matter when we could have been donating to the cause or contacting public officials.

I applaud all those who echo educational messages and news about whatever new horror seems to be unfolding in our world today. But to be a true agent of change, you should use these messages as a supplement to donating your money and time.

Whatever assets you have can contribute to a crisis relief effort. Your money could help Ukrainian refugees as they flee their country, support the opposition press in Russia, and aid organizations that can provide medical assistance to the Ukrainian army.

You do not even need to be super wealthy to make a difference. Even incremental amounts of $5, $10, or $15 can help. You may have to forgo a few morning cold brews, but the potential benefit of preventing mass casualties should be enough to incentivize you to put your money where your mouth is.

Shiv Bailur is a first-year social sciences student at University College.