In the aftermath of the Second World War, artists responded to grief, confusion, and mass destruction with something that seems equally arbitrary: absurdism. Featuring many tragicomedies trying to explore the human experience in what seemed like an irreparably chaotic world, the absurdist movement has always spoken to that part of me that wishes to just exist, both in a state of ecstasy and complete and utter desolation.

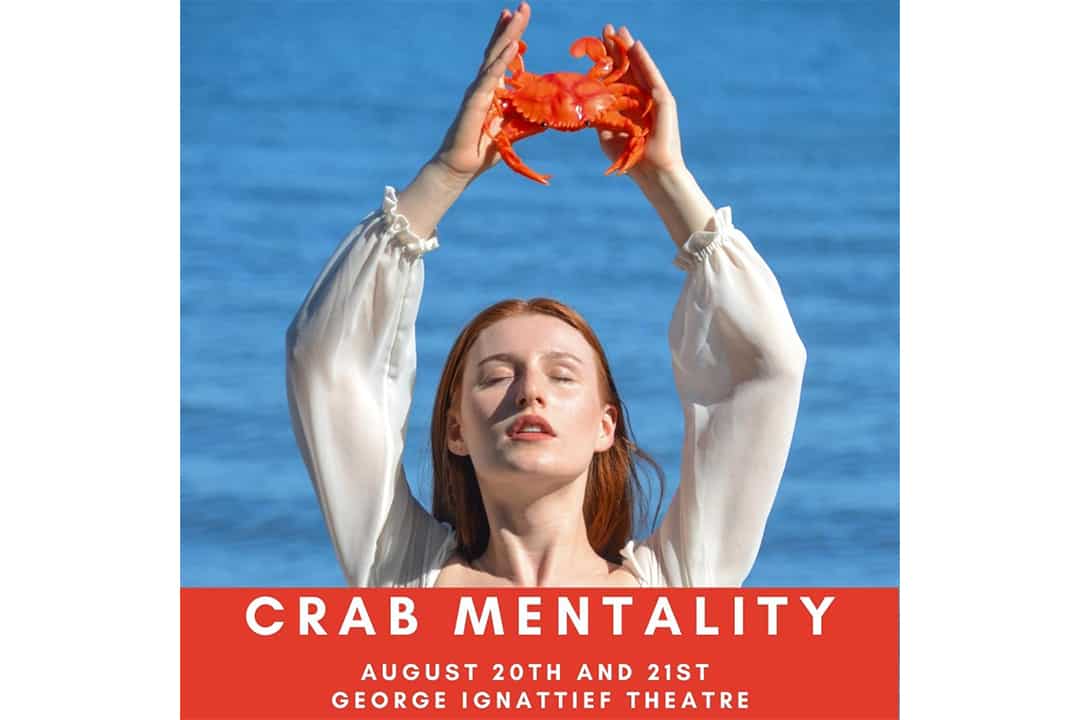

Now, in the wake of another global trauma in the form of the pandemic, artists seem to be rediscovering the pleasure in chaotic revelation. There is no better example of that than Crab Mentality, an absurdist play set to premiere for free at the George Ignatieff Theatre on August 20 and 21 at 7:00 pm and 1:00 pm, respectively.

The play was written by U of T students Chloë Rose Flowers, Molly Dunn, and Raquel Ravivo, and was funded by the Victoria College Student Project Fund. With production support from fellow U of T students Emma Kacur and Cass Iacovelli, Flowers, Dunn, and Ravivo feature alongside Nick Cikoja and Jordan Chan in a cast of five characters who wake up on a deserted island with no memories. Over the course of the piece, their adamant worship of a crab leads them to descend into emotional and physical chaos.

The Varsity got the opportunity to speak with Flowers and Ravivo at their rehearsal space in the Sir Daniel Wilson Residence building about the play’s themes and production process, as well as its impact on their university experience. What emerged was their passion for both literal and figurative play, absurdity, the craft of theatre, and the strength of the U of T theatre community.

The playfully absurd

Hindsight is truly 20/20. Though Flowers, Dunn, and Ravivo didn’t set out to write an absurdist play, their devised theatre methodology certainly lends itself to such a chaotic genre. In devised theatre, a piece is written while it’s being created in a wholly collaborative process.

Flowers told The Varsity that they thought of the concept after discussing a real American crab cult while on a writing break. What started as an unbelievable news story quickly unravelled into a play that thinks deeply about how belief systems develop.

“[It’s] this sort of broader exploration of how… power systems and belief systems form around the individuals who create them,” Flowers said. “On the other hand, we were literally creating a religion based around this crab. And we have ‘crabmandments,’ we have crab sacrifice, we have immaculate crab-ception — we have the bunch.”

Flowers admitted that they took a risk by following their instincts and writing such an abnormal play. In fact, when Flowers, Dunn, and Ravivo approached the Victoria Student Project Fund, the play hadn’t even been written yet, which they had to explain was a cornerstone of the play. Though the play mostly came to fruition due to the self-initiative of the students creating it, Flowers emphasized their gratitude for the Victoria Student Project Fund, which also took a risk by funding the production.

Their production process also reflected the students’ playful, instinct-based mentality. The actors were instructed not to read the script before the first table read and to refrain from skipping ahead while the table read was happening so Flowers, Dunn, and Ravivo could see their immediate reactions. Afterwards, they decided to improvise the whole show on the spot.

“It was so fun and joyous and cathartic,” Flowers said. “I think the most enjoyable theatre for me personally is theatre that takes risks. And we were playing. That’s what we were doing — following the urge to just play. That, I think, is something that was suppressed a lot by the pandemic.”

The result is a fast-paced play that sucks the audience into its tumultuous world. It explores the extremes of human emotion, creating an experience of emotional whiplash that finds itself at a halfway point between thought-provoking and entertaining.

Staging violence

There are other ways in which the play is a response to the pandemic. For one, it contains a lot of movement, specifically in the form of violence. According to Flowers, this aspect of the play came out organically through the creative process, and it is often a manifestation of the characters’ anger and their attempts to maintain control.

“It’s almost like you have five burners in a row and five pots of water on top of those burners,” Flowers explained. “Throughout the play, somebody is raising and lowering the heat on each of those burners. You sometimes see the characters bubble and simmer and sometimes they explode and overflow and then they go back down to being contained.”

Due to all the violence in the play, the actors were similarly challenged to think about containment and control. Flowers explained that the process was a great learning experience in stage combat and stunt work.

Flowers brought Fight Instructor Nicole Moller on to help with the stage combat choreography, which has to be very precise and tight to ensure that no one gets hurt. The actors finished many rehearsals in exhaustion because of the physical toll that practicing stage combat takes on the body.

It can also be mentally stressful — stage combat is always victim controlled. For example, if you watch one character pushing another on stage, the instigator’s blow shouldn’t have any real force. Instead, it’s up to the victim to act out the strength of the hit. As a result, the whole exercise demands a lot of trust.

In turn, that mental strain further contributes to the physical strain. Ravivo noted that since you can’t propel your force outwards, it manifests in your body instead. Oftentimes, the actors would be physically shaking while enacting violent scenes. “You’re showing that anger in your body … you’re literally tensing every muscle in your arm,” Ravivo said.

After our interview, I stayed back to watch the cast practice some of the more violent scenes in the play. Despite the sunlight streaming through the windows and the stripped-down set up of the rehearsal space, I was still shocked and captivated by the events unravelling before me.

The violence felt real, but what felt even more real was how that violence pushed and prodded at the emotions of all the characters, how it pushed them toward their limits. Though not a play for the light of heart, it will certainly be an experience that audiences will not soon forget.