King Lear is having a bit of a moment. At the beginning of the pandemic, the claim that Shakespeare wrote the play in quarantine gained traction online; this March, campus theatre group Trinity College Dramatic Society aired a digital production of King Lear; and this summer, popular British playwright Tim Crouch premiered a fantastic new virtual reality infused riff on it, Truth’s A Dog Must to Kennel, at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Now, one of Toronto’s largest theatre companies, Soulpepper, is getting in on the action.

Until the first weekend of October, the company is presenting two King Lear-related productions in repertory: King Lear and a new prequel about Lear’s eldest daughter, Queen Goneril, by Erin Shields. In King Lear, Goneril is essentially a villain; Queen Goneril is her origin story. King Lear runs three hours and 45 minutes with two intermissions, and Goneril runs two hours and 40 minutes with one intermission. Together, it’s a nearly six-and-a-half hour theatrical experience. And there are free tickets for people 25 and under.

Since Soulpepper often works with the same designers, a lot of their shows share an aesthetic. I’d describe it as “realism with fancy transitions”: all the scenes are performed realistically, on fairly detailed sets; then, when it’s time to transition between scenes, the actors slowly change the set while creative sound, lighting, and projection design keep the audience entertained. This aesthetic is not inherently problematic, but if the scenes are not executed perfectly, the transitions can end up being the most engaging part of the show.

If nothing else exciting were happening, this is the aesthetic to which Queen Goneril, directed by Weyni Mengesha, and King Lear, directed by Kim Collier with assistant direction by U of T alum Will Dao, would default. But lots of other exciting things happen.

For instance, monologues. Like most Shakespeare plays, King Lear is littered with monologues addressed to the audience. Even if a scene is being treated realistically, when an actor begins one, they must acknowledge the audience’s presence and break all pretences of realism. They are moments of pure theatricality. In King Lear, the characters with the most monologues are probably Lear and Edmund, played by Tom McCamus and Jonathon Young, respectively. McCamus and Young navigate their characters expertly, developing a connection with the audience so intimate that we begin to feel like all their lines are addressed to us, monologue or not.

For Queen Goneril, Shields gives the monologues to the women. As you’d expect, Goneril — played by Virgilia Griffith — and her sisters have plenty, but so do the female side characters. In a highlight moment, even Lear’s maid, played by Nancy Palk, gets the chance to tell us about her secret habit of digging through “kingly excrement” for swallowed treasures. It’s fairly rare to see monologues like this in a contemporary play, so this is a welcome move from Shields.

Another exciting element is the storm that takes up most of King Lear’s second half. To render it, set designer Ken Mackenzie switches out the more realistic sets of the play’s first half for a mostly empty stage; in the distance, sound designer Thomas Ryder Payne conjures booming thunder, and lighting designer Kimberly Purtell, who is a U of T alum, invokes flashing lightning.

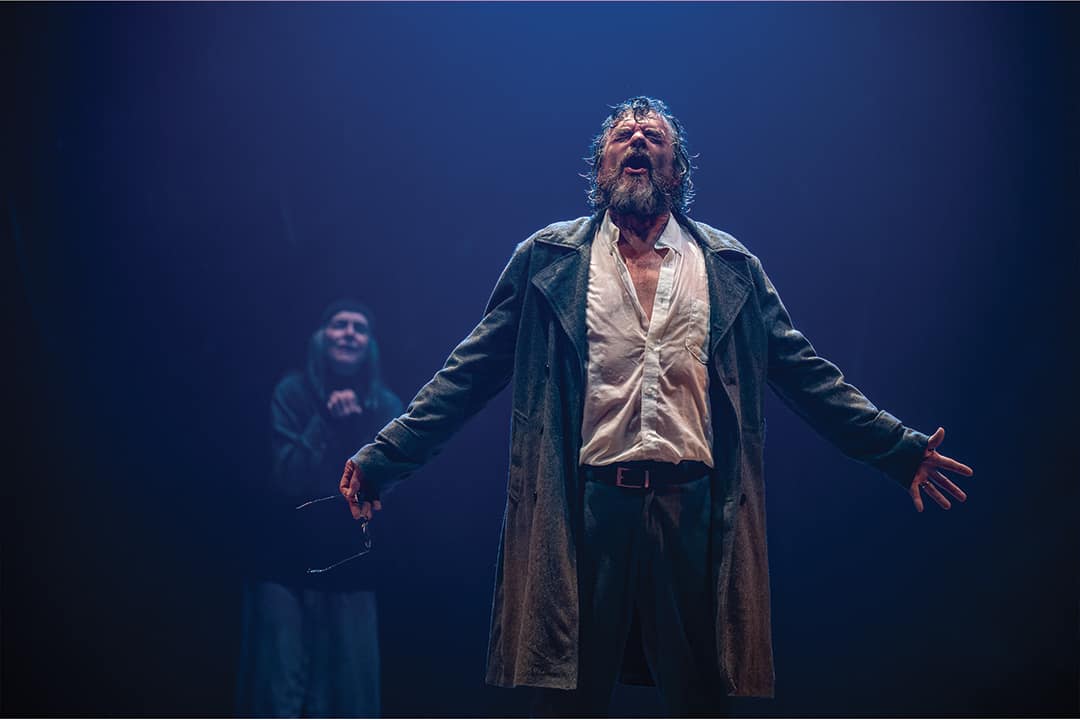

The second act feels especially void: much of the action takes place on a black tarp at the front of the stage; Lear sits shirtless in this abstract space, playing with his shoe, staring at us, smiling and giggling; he’s a baby again, we’re all babies again, we are nowhere and everywhere and nothing else matters but this irreducibly theatrical moment. It’s thrilling.

As King Lear races towards its tragic end, it stops mattering where we are. Lear’s mind deteriorates and the world around him blurs into an abstract haze.

Not so in Queen Goneril. While, like Lear, Goneril and her sisters venture into a storm to scream at the gods, the sisters’ story does not ultimately devolve into abstraction. After their emotional night in the storm, the women return home, and the subsequent final scene is twenty minutes of cold, brutal realism. It has none of the theatrical excitement of the storm. At the preview performance of Queen Goneril that I saw, this frustrated me. The storm was formally interesting, and I wanted more of that theatrical fun. When I went back to see the show again, though, I realized I’d missed the point entirely. Goneril doesn’t get the fun ending. She doesn’t get catharsis. Hers is a tragedy of mundanity, not of dynamism.

And as Goneril boredly waits, the men play. Goneril warns her sister Regan, played by Vanessa Sears, that “men are unpredictable when they’re drunk.” In that case, then, men are always unpredictable, because, in Queen Goneril and King Lear, the men drink constantly. Lear’s right-hand man, Gloucester, played by Oliver Dennis, brings Lear fancy wine to taste before noon; hunting trips are a chance to drink and gossip; and the men’s raucous parties leave Lear blackout drunk, clamouring for motherly love. This continues deep into the third act of King Lear: as Gloucester roams around the storm, blinded, he has nothing left. Nothing, anyway, but a bottle of liquor. It’s a rich visual motif.

But perhaps the greatest boon of the double bill: it’s a fascinating actorly showcase. McCamus is brilliant in King Lear, but, in Queen Goneril, his subtle explorations of the early cracks in Lear’s foundation are just as good. Similarly, while Griffith is unstoppable in Queen Goneril, King Lear is where all that backstory pays off: hers must be one of the most layered ‘Gonerils’ ever seen. And all the actors have thought through their characters just as deeply. You could watch any of the group scenes ten times over and still find new dynamics at play.

My nitpicks mostly regard temporal settings. While the mix of contemporary and period sets work for King Lear because it’s an old play from a distant culture and we can relish in that friction, it makes less sense for Queen Goneril. When the show asks us to judge the morality of social customs like arranged marriage, it becomes confusing: by what values should we judge these characters? In the culture of Queen Goneril, how are these customs usually navigated? There’s not enough social context to be sure.

But this is vital theatre. Queen Goneril seems destined to become a theatre school staple, and King Lear marks a triumphant return to Soulpepper’s classical roots. The reason the company gets over a million dollars in annual public funding is to do work like this.