I used to compete with newspapers for my mother’s attention when I was little. I couldn’t understand the charm of writing — that is, until I learned how to read.

From the Narnia chronicles to Charles Dickens, I matured with the books I read. My perspective of the world expanded from realms of fantasy to real-world issues. But, as I broadened my scope of reading, I realized how digital media forces us to re-evaluate the social impact of published writings.

In this feature, I explore some of the issues associated with journalism and digital media, the outlets responsible for passing the weight of words to the public. I hope that what I found can create conversations about how writing shapes the world as we know it.

From the very beginning

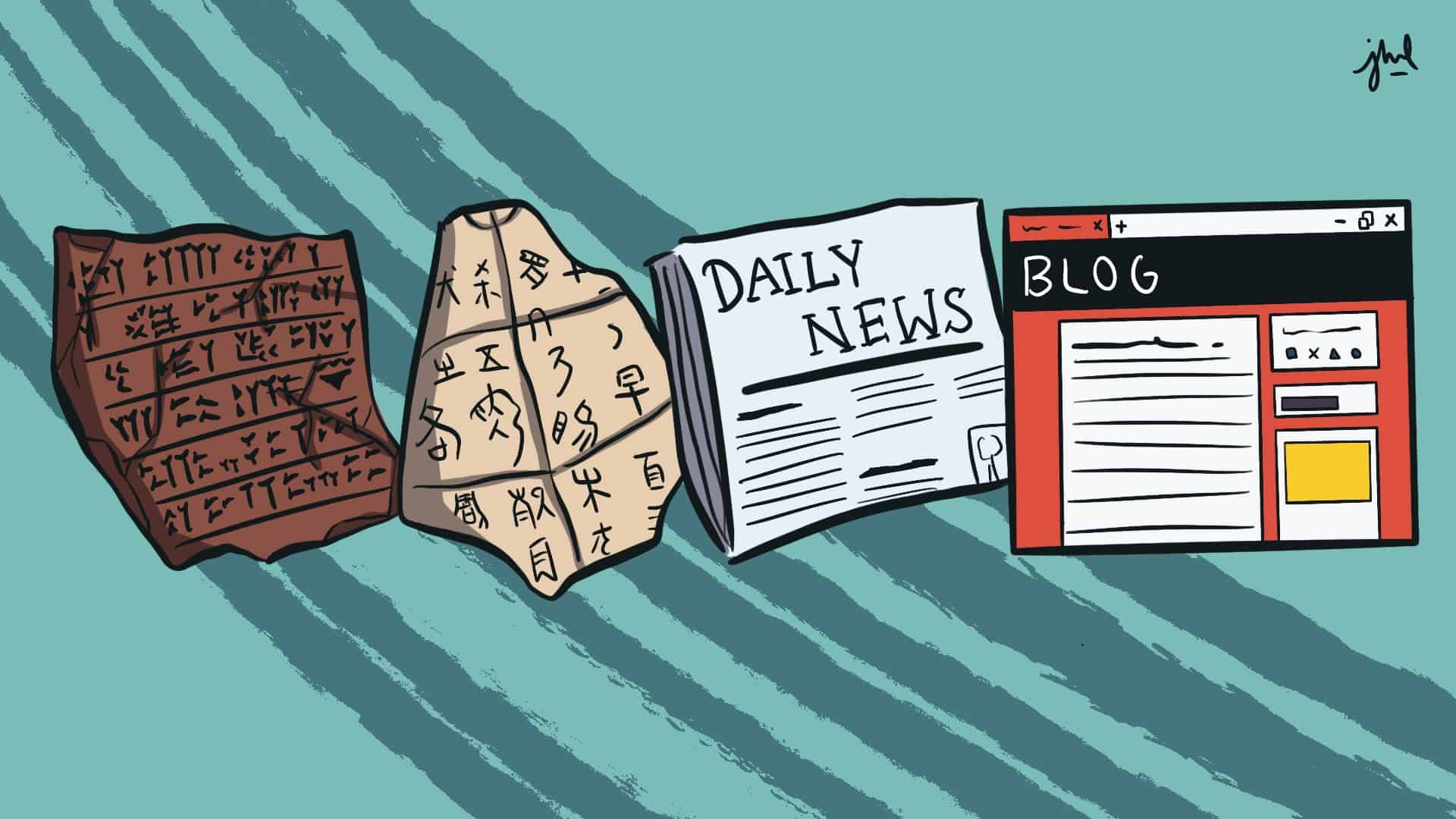

Words are a currency for preserving the collective memory of humanity. The exercise of writing — whether it be scratches on papyrus paper or typing with keyboards — has evolved alongside human civilizations globally. At U of T, the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library and the Robertson Davies Library have collections of some of the earliest known human writing: clay tablets from the Babylonians, the oldest of which date back to 1,789 BCE.

The tablets’ cuneiform script — a wedged-shaped writing style that resulted from pressing a stylus into clay — laid the groundwork for a writing system. Cuneiform was first invented to record Sumerian, but survived beyond the era when Sumerian was the main language of learning in the Middle East. Cuneiform evolved into the writing system for other spoken languages in the region, such as Akkadian, Elamite, and Hittite. Although cuneiform was eventually replaced by alphabetic writing in the first century AD, its significance as the first true writing system is undeniable.

To learn more about ancient writings, I spoke with Professor Alan Galey, director of the Collaborative Specialization in Book History & Print Culture, a graduate program at U of T. Galey encouraged me to look beyond “Western forms of writing” since history has traditionally been understood from an imperialist lens, which has distorted the public understanding of book history.

Galey also mentioned that Indigenous forms of writing were not widely recognized by academic scholars until recently. In Onondaga and Haudenosaunee cultures, the Wampum belt — woven from strings of white and purple shell beads — is used for recording details of important functions, such as large council meetings. The initial strings on woven Wampum belts are meant to record an agreement reached at a particular meeting. Through hand weaving, the Wampum belt lengthens to follow-up on the subsequent development of the first agreement. Hence, it is seen as a living record of the Onondaga and Haudenosaunee “living history.”

After the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, monasteries hid medieval books from barbarians’ assaults and chaos. Hence, the publishing and preservation of books fell into the hands of monks. Until the invention of the printing press around 800 AD, people around the world carried out bookmaking entirely by hand. Later, in the fifteenth century, Johannes Gutenberg established a distribution network for books that allowed writings to reach a wider audience and powered the spread of scientific findings and data.

Political polarization in Canada

Exploring how writing has evolved throughout human history inspires me to ponder how words change humanity — for better or worse.

Modern-day presses, whether they produce books or newspapers, continue to resist attempts to censor ideas contrary to mainstream discourse, which supports those in power.

I interviewed Eric Merkley, an assistant professor at U of T’s Department of Political Science. Merkley highlighted trends in Canadians’ news consumption, mentioning that Canadians “prefer [to read] news content that aligns with their political beliefs.”

A likely source of Canadians’ feelings is the phenomenon of political polarization, which happens when people stick to distinct ideological extremes, as opposed to having moderate views. Political polarization can lead to affective polarization, which is when these differences in views lead to people disliking and distrusting those on the other end of the political spectrum.

However, if you’re labelling those who disagree with your political takes as “un-Canadian” to win an argument, this undermines the value of democracy. The us-versus-them divide could create an atmosphere that is conducive to radicalization, therefore drawing society closer toward politically motivated violence. In contrast, having dialogues to resolve disagreements across partisans promotes mutual respect and stability.

When we migrate these political dialogues to online platforms, we turn political polarization digital. In 2014, Anatoliy Gruzd and Jeffrey Roy — professors at Toronto Metropolitan University and Dalhousie University, respectively — published a study that investigated the influence of Twitter on Canadians. Results showed that around 47 per cent of messages exchanged between left- and right-leaning supporters were either negative or hostile.

The cross-ideological discourse that the study observed acknowledges that party supporters are aware of opposing viewpoints on Twitter. But, in the case of nonpartisan citizens, the links to news articles and websites found in short tweets could facilitate additional learning. Open access to online cross-partisan exchanges may better prepare people to make informed decisions about which party to support.

Although the usage of social media or online news outlets could lessen the impact of selective exposure, we must be wary of the abundant amount of online content we’re exposed to that could be inauthentic and inaccurate. Keep in mind that contemporary journalism is accountable for transforming complex political happenings into news stories that are comprehensible to the public.

What is true journalism?

To learn more about the impact that social media has on public discourse, I reached out to Jeffery Dvorkin, a senior fellow at Massey College, who is the former Managing Editor and Chief Journalist for CBC Radio.

Dvorkin clarified the distinction between evidence-based and opinion journalism. He said that the former informs its audience of current events as transparently as possible through sources, while the aim of the latter is to persuade, which entails disclosing to the audience that these commentaries are based on facts. Opinion journalism justifies the establishment of editorial pages for the publishers to express their points of view. To address other opinions in the publication, an op-ed — opposite the editorial page — is dedicated to publishing opinions by individuals based on those individuals’ interpretation of facts.

Dvorkin said that subjective and objective opinions are equally important in newsroom productions — this caught me off guard. Dvorkin’s remark revolutionized how I personally perceive the role of journalism: “[If] journalism is only going to be neutral, then that’s not journalism [but] stenography.” I have somehow always thought of journalism as a method of delivering information. After speaking to Dvorkin, I came to appreciate how analysis and interpretation in news reporting are indispensable elements of journalism.

Be critical, not cynical

Our trust in journalism is fast dwindling. This is a consequence of the massive digitalization of information consumed by the general public.

Journalists used to be gatekeepers that intercepted and decided which threads of discussion to report on, further investigate, or reject. With newspapers and broadcasting companies increasingly relying on the internet, few to no barriers exist when it comes to sharing information. To entice audiences to keep reading, some professionals choose to report in the format of ‘infotainment,’ which is integrating more popular cultural elements into formal reports. The rise of infotainment is the root cause of the increasing elements of sensationalism in news stories that are selected for their entertainment value instead of their relevance to the wider public.

When interpreting media, another unexpected source of confusion is our social circles — which oftentime include our families. I am not making a case against dad jokes and mom memes; instead, I urge you to pay attention to the social media posts that loved ones share. When others repost content that your loved ones have shared, their body will release endorphins, which initiates a behavioural reaction that makes them prone to continue to post. As these posts reach more people in their network, this cycle repeats itself.

The most sensible way to prevent these mistakes from affecting you is to detect confirmation bias — this means noticing how your existing beliefs could make you ignorant of inconsistent information. We must identify sources of information that are most likely to comfort or enlighten our loved ones’ political affiliations. Furthermore, we must be critical of institutions or media organizations that the shared content originated from.

When we try to resolve complicated situations via simple solutions, we are prone to make errors. As Dvorkin said, we can verify the credibility of a source by finding out “who’s behind [publishing the information], how to get in touch, ways to file complaints, and [the publication’s source of] funding.” These are the basic elements of a credible source.

Strengthening public accountability

In the age of social media, news reaches a much wider audience than in times before the internet. This larger audience means that readers may point out errors or miss elements in every published news story. This pressure forces news organizations to directly respond to online criticism in a timely manner. Dvorkin calls this the “democratization of media” in his recent book Trusting the News in a Digital Age: Toward a “New” News Literacy.

Bloggers and podcasters are the main pillar in the so-called non-professional “citizen journalism.” However, the presence of online influencers makes watchdog journalism — in which journalists fact-check and interview public figures to increase accountability — thrive over mainstream media. Whether watchdog journalism is enough to reverse the trend of decreasing readership and restore public trust in mainstream news still remains unanswered.

A great challenge in journalism is making the public feel connected to news organizations. Dvorkin recounted when public editors were hired by the news media industry in the early 2000s. The main responsibilities of public editors entailed managing audience engagement. Public editors may have also defended news organizations when widespread criticism did not align with facts or context based on their previous journalistic foundations.

The Varsity hires a public editor to maintain its integrity and relevance to the U of T community. However, affordability may be why some media organizations do not hire a public editor; many organizations may encounter financial difficulties, especially during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

What to do without

The quality of newsroom production is unavoidably dependent on budget and funding. Media organizations are troubled by insufficient funding, yet excessive influence from shareholders may jeopardize the integrity of their news reporting.

Financial stress in the limited budget for foreign news could lead to a “what are we willing to do without” approach to writing and broadcasting stories. Only large amalgamations of business entities or government funding have pockets deep enough to cover the cost of investing in information gathering. For example, there is little direct on-the-ground reporting on conflicts in Afghanistan due to expensive war insurance for reporters.

To fill this gap in reported content, journalists turn to either opinionated journalism or local news — this means weather, traffic, and crime. This practice blurs the distinction of opinion stories from firsthand news reporting. As defined by the New York Times, primary news should not involve any levels of analysis. When newsrooms over-rely on the “low-hanging fruit of local news,” as Dvorkin put it, to sustain cheap operations, they sacrifice in-depth coverage of world events.

Many news organizations are trying to get rid of high-paid senior staff in exchange for young journalists. The attempt to cut down labour costs triggers a growing preference for newsrooms to deliver news in digital format. There are large media companies acquiring smaller online news outlets, which means analysis of currents may be homogenized in essence but packaged differently.

As this trend unfolds, the development of public media literacy is more important than ever. Merkley said that media literacy “means educating people on the norms… in mainstream journalism and how to spot low-credibility or hyper partisan news.” Besides verifying the background of sources which supply the information, the trustworthiness of news organizations hinges on contextualizing that information.

The non-duality of writing

I realize that the act of writing is neither inherently good nor bad. Most people associate self-censorship with infringement of the freedom of speech. I, too, initially posed interview questions with the assumed toxic nature of censorship.

Galey noted that the practice of editing and revising in publishing bridges the gap of understanding between readers and writers. The aim of editing in journalism is to ensure accuracy instead of suppressing the writer’s voice. Freedom of speech is in no way compromised by fact-checking or verification; rather, revisions enhance the accountability of shared information.

Just like how artists interpret a piece of art, humans give political and economic significance to reading and writing. Writing can cause seismic divides in society, but it can also unite countless people through their shared feelings. From the ink of ballpoint pens to fingers dancing on keyboard floors, the spread of literacy and public education gave us the power of writing. When wielding it, we must keep reminding ourselves to express our ideas with accountability and originality. I truly believe that we can change the world for the better — one word at a time.