Making an adaptation is hard.

As a creator, you have to justify the existence of a new version of a beloved media franchise while appeasing the ravenous hordes of fans ready to tear apart your creation because you didn’t fit the community’s preconceived idea of the piece.

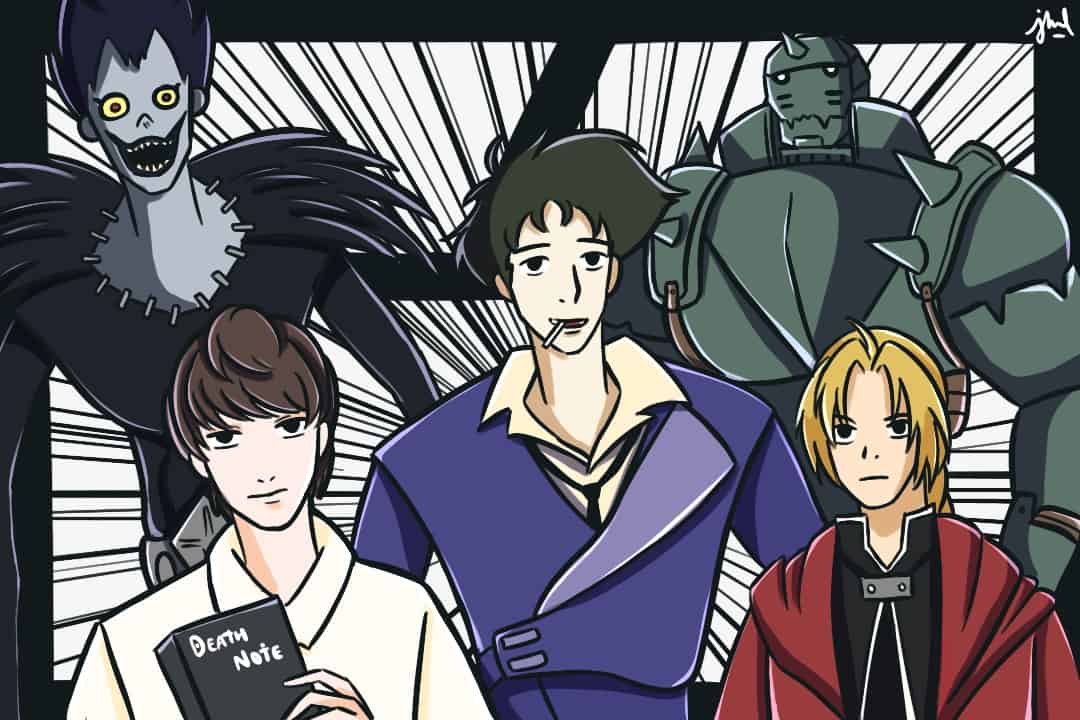

That being said, some adaptations just fall completely flat on their face. In my opinion, no genre of media is more guilty of this than anime. For this article, I put myself through the hellish experience of watching some pretty bad live-action anime adaptations to investigate why they seem to consistently fail.

Someone, please put my name in that notebook

When I first thought of anime, I thought of Death Note. It seemed like a really good entry point if someone wanted to start watching anime; it has compelling characters and an interesting concept, wherein if you write someone’s name in a supernatural notebook, they die. Naturally, I decided to start with its live-action adaptation, which is a movie instead of a TV series.

Oh my god.

It was awful.

The acting was drier than a box of crackers left in the Sahara. The plot, upon closer inspection, was thinly stringed together at best. The worst part of the whole thing, however, was the perversion of the core characters and the removal of the terrifying element of the Death Note.

The character of Light Turner — known in the anime as Light Yagami — is the clearest example of this perversion. In the anime, Light Yagami is a cold, calculating sociopath who routinely uses and discards people. In the live-action adaptation, Light Turner is an overly hormonal, easily manipulated teenager. Worse, they eliminate Yagami’s zealousness and his steadfast belief that he needs to rid the world of criminals and those he deems to be evil.

That change in character removes a lot of the fun present in the anime. Watching each episode you’re constantly asking yourself, “How far will Yagami go?” And the answer is “far, very far.” But in the live action, that just isn’t there.

What is even more disgraceful is how the live action sheds what makes the Death Note so damn terrifying: its supernatural power to kill anyone at any time. The first time viewers see Yagami use the Death Note in the anime, he uses it on a criminal on the news who’s taken a daycare centre hostage. Though Yagami initially dismisses the notebook as a prank, he soon changes his mind when the criminal drops dead from a heart attack.

In contrast, Turner’s first victim dies of decapitation, and the scene depicting the death is comical. The bully is killed in a mix of Rube Goldberg machine and butterfly effect style events that cause his decapitation. Instead of emphasizing the Death Note’s power, the scene discredits it.

If the Netflix live action were more true to the main characters and stuck to the terrifying supernatural element of the Death Note, it could have been a better live-action piece. Cramming the story into an hour and forty minute movie also didn’t help its quality.

Time to wrestle up some cattle

Netflix’s live-action Cowboy Bebop TV series suffers from the same issues as the Death Note movie: changes in characters that affect the overall feel of the story. This is most seen in the anime’s antagonists, Vicious and Julia.

For one, the Netflix series attempts to portray Vicious in a more sympathetic light by showing how he was abused by his father, which then twisted him into the psychopath we see on screen.

But that doesn’t work. The reason why Vicious’s character works so well in the anime is that he’s completely dispassionate and power hungry. While in the anime, Vicious does attempt to get revenge on Spike — the protagonist of Cowboy Bebop — for taking Julia away from him as well as for leaving the Red Dragon Crime Syndicate, the crime organization for which they both worked, Vicious’s feelings for Julia are about control: if I can’t have her, he seems to believe, no one can.

In the live-action, Julia stays with Vicious out of fear that he would otherwise kill her. That alters the dynamic between Vicious and Spike, as Vicious is no longer a dispassionate force but instead motivated by emotion: his “love” for Julia. He becomes more of an overly emotional man-child rather than the cold killer he should be.

This brings us to Julia. Though it’s good that the live-action makes her an active character — if someone is being chased, they should probably have a more active response to it — it messes with the original source material and, therefore, demands that a whole new story be written.

The story Netflix came up with isn’t good, which is even more painfully clear when it’s compared to the anime’s story.

I should’ve majored in alchemy

Our final entry in this saga of pain comes in the form of Netflix’s live-action adaptation of Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood. All things considered, it wasn’t too bad. It didn’t have the charm of the 2009 anime but the special effects helped hold it together.

Where I take issue is the fact that they didn’t do anything interesting at all with the characters. While Netflix’s live-action Death Note and Cowboy Bebop try to do something different with their characters and story, Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood doesn’t. The main characters Edward and Alphonse Elric are unchanged, as is the majority of the supporting cast, barring Shou Tucker.

I welcomed the change in the character of Tucker, but it also had some key issues. In the 2009 anime, he was designed as a character to only be present for one episode to help the Elric brothers in their quest to reclaim their original bodies. In the live-action, he stays alive until close to the end of the movie.

While Tucker’s continued existence did allow the characters to jump from one plot point to the next in ways that differed from the 2009 anime, it felt like a strange aberration in the story, and he grew more shallow as the plot went on.

Interestingly enough, the failures of all three of these adaptations centre on characters. Either the writers failed to account for how their changes to characters would affect the story, or they failed to do anything with them at all, leaving the adaptation feeling hollow and flat.

But maybe this can be a cautionary tale for future adaptations. Maybe it will push writers to investigate an anime’s established personas and use them to create original works out of beloved franchises. And if that doesn’t happen, then I would at least recommend you hate-watch these movies for the laughs and entertainment value.