On September 8, a pair of brilliant rainbows took shape above the grounds of London’s Buckingham Palace. Their timing was what some people might deem worthy of a storybook; the rainbows came shortly before Britain’s Royal Family announced the death of its monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. Mere hours after, rainbows were spotted above both Windsor and Balmoral castles — the former a royal residence in southern England and the latter the Scottish estate where the Queen passed away.

Kirsty MacLellan, a fourth-year U of T student, might have caught a glimpse of the last rainbow if she had still been living in Scotland. Instead, MacLellan — who received Canadian citizenship in 2021 — sat in a UTM classroom, awaiting her professor’s arrival for the first class of the academic year. By the time her professor arrived, most of her peers had already filled the room; they watched half-heartedly as the professor unpacked their belongings.

“By the way, the Queen died, everybody,” said MacLellan’s professor, looking up from their rummaging. It wasn’t a grand announcement; mere seconds afterward, the professor’s head was down again as they gathered loose papers from their work bag. The words’ effect, though, was clear: one of MacLellan’s peers gasped, their breath replaced by a pause that flooded the room.

Finally, another student broke the silence: “Can we have a party now?”

Though MacLellan’s professor didn’t acknowledge the student’s words, the joke made an impression; half the class chuckled, while the other half stayed silent as if in disapproval.

MacLellan’s class was a seminar; she was one of no more than 15 students stationed around her classroom’s boardroom table. Though the group was tiny, the students’ mixed reaction perfectly summarized the feelings of the world — and the U of T community — following the death of Britain’s longest-serving monarch.

Over the past week, we’ve witnessed international leaders, such as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, praising the Queen for her service and leadership. We’ve seen military parades march past Parliament Hill and have heard 14 minutes of gunfire tributes. At U of T, we’ve seen all three campuses lower their flags to half mast, and we’ve watched the carillon bells at Soldiers’ Tower toll 96 times, each for a year of the Queen’s life.

Similarly, we have observed the sentiments of those who are not mourning. We’ve read pieces in TIME, The Harvard Crimson, and CNN calling out the British monarchy for racism, and we have watched Australian senator Lidia Thorpe, an Indigenous woman of DjabWurrung, Gunnai, and Gunditjmara descent, call Queen Elizabeth II a “colonizing” queen during a swearing-in oath.

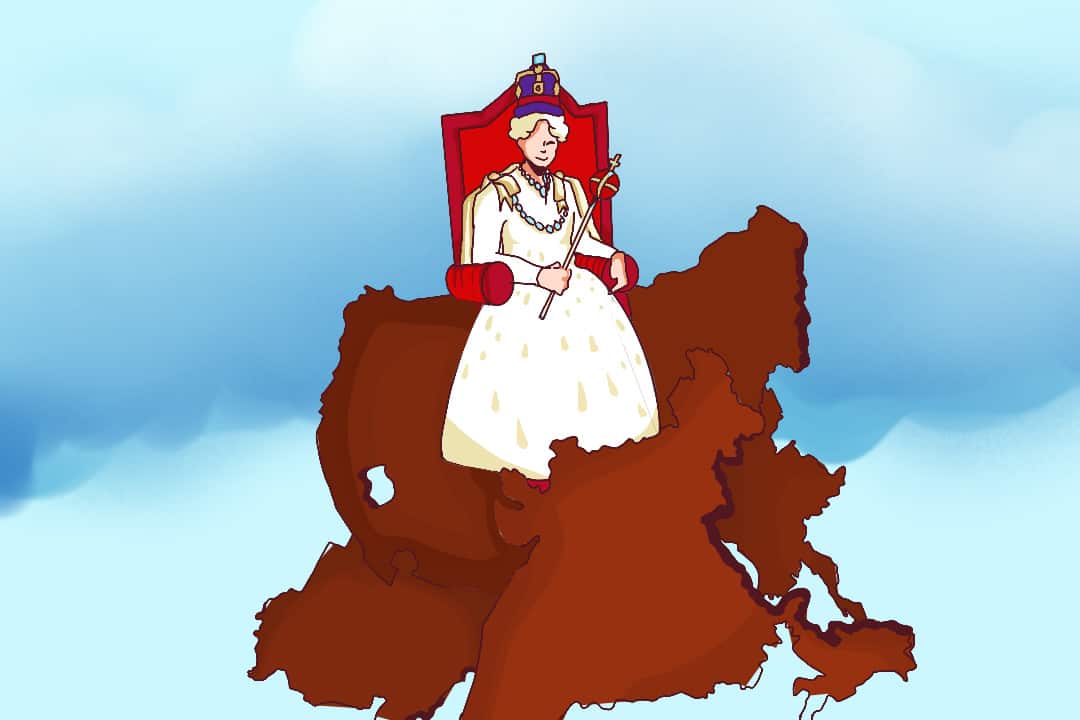

For all of us, the Queen’s death is an historical event — the Queen had an unprecedented 70-year reign and was the “the last major historical figure of the 20th century,” according to the Toronto Star. However, the Queen — a figure who, to some, represented a calming constant in a chaotic world — was also innately tied to a colonial past, one whose lasting effects shape many U of T students’ lives today.

U of T’s reflection

Hours after the announcement of the Queen’s passing, U of T President Meric Gertler released a statement: “The University of Toronto community joins all Canadians in mourning the loss of our Sovereign, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II,” he wrote.

Gertler continued: “Before she acceded to the Throne… She promised that her whole life would be devoted to the service of her people. She fulfilled that promise with unparalleled grace and dignity.”

In a statement to The Varsity, a U of T spokesperson wrote that the university “occasionally issues institutional statements about major events that directly affect our community.” The spokesperson further explained that, because Queen Elizabeth II was Canada’s head of state — a role that the spokesperson described as “key… in our system of constitutional government — the university felt that her death “merited such a response.”

The U of T spokesperson also described the university’s statement as being “consistent” with public statements issued by all levels of government, including by Mary Simon, Governor General of Canada, and by Elizabeth Dowdeswell, the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario.

However, some students were upset that Gertler’s statement, which was made on behalf of the U of T community, did not acknowledge Britain’s history of colonization. After all, out of the world’s 195 countries, Britain has invaded 171.

Scotland, the country that McLellan immigrated from, united with England in 1707 to gain economic security and access to England’s colonial trade network, despite a long history of distrust and conflict between the two nations. In this union, Scotland retained its legal, religious, and educational systems but joined the main British Parliament with a disproportionately low number of representatives.

The union was unpopular among the Scottish and sparked rebellions in 1715 and 1745. The British government also implemented policies that evicted inhabitants of the Scottish Highlands and western islands of Scotland for sheep pastoralism, as well as eliminated supporters of Catholicism in Scotland.

“How can [Gertler] say that on behalf of people whose entire lives or entire histories have either been erased or changed by the Queen’s colonies?” McLellan asked. “How can [he] be part of one of the top universities in the world and say that?”

Sara Sullivan, a fourth year English student from Australia, added in an email correspondence with The Varsity: “U of T has a duty to recognize the painful past and present experiences with the crown of many people from around the globe.”

Separating the Queen from history

As the reigning British Monarch, Queen Elizabeth was Canada’s Head of State — meaning that, in Canada’s system of government, the monarchy gave the Canadian government the power to rule on the Queen’s behalf. Great Britain began acquiring territory in what is now Canada in the 1600s, and the Queen remained our head of state when the Dominion of Canada was formed in 1867.

Eventually, the British Empire became too large to manage efficiently. In the nineteenth century, the empire began developing a system under which, for domestic matters, ministers elected by their colonies could exercise executive powers instead of limiting those powers to officials chosen by the British government. In 1931, the Statute of Westminster recognized members of the Commonwealth as independent countries within the British Empire that are “equal in status” to the United Kingdom. Some of these member states make up the modern Commonwealth, which any country can join.

The monarchy regularly uses the British Empire’s symbols and familial language. For example, the Union Jack, the flag used for the United Kingdom since 1606, has been an enduring motif in various flags flown in former British Colonies. Given connections like this, some students view the Queen — the monarchy’s head — as a symbol of racial and economic power.

Zyad Osman is a political science and human geography major with a background in Egypt. Britain ruled Egypt from 1882 to 1914, beginning during the Anglo-Egyptian War and ending when the Ottoman Empire joined World War I. Egypt declared independence in 1922, but Britain did not withdraw its troops until after the 1956 Suez Crisis. In an email to The Varsity, Osman connected his sentiments of the Queen to a quote by James Connolley, an Irish Marxist Leader, that suggested that members of the monarchy shoulder the responsibility for their ancestors’ crimes.

“Queen Elizabeth [II] bore the responsibility for the atrocious actions committed by the British Empire in Egypt and the rest of the colonies unless she confronted this past or relinquished this right,” wrote Osman.

However, other students stressed the importance of separating impressions of the Queen from Britain’s complicated history of colonialism.

“People have a myriad of opinions [about] the monarchy, and that’s fine,” expressed Sullivan. Sullivan was born in Australia, which the British colonized in 1788 before the colony became a founding member of the Commonwealth in 1949. During British settlement in the country, settlers killed more than 20,000 Indigenous peoples over access to their occupied land.

“What isn’t fine, in my opinion, is to disrespect a woman who served her country and her family in an unimaginable way for the majority of her life,” Sullivan wrote.

“The Queen herself, Elizabeth Windsor, was extraordinary for her time,” added Sullivan. Sullivan highlighted that as the daughter of a second-born son, Queen Elizabeth II never thought she would become a ruler at the age of 25. “She wasn’t all that much older than the majority of us, [and] she gave up her own ambitions and dreams in order to serve her people.”

Serving her people

In tributes, many international leaders have drawn attention to Queen Elizabeth II’s life of dedication; however, many of the people in question were unwillingly subjugated to the institution she represented. Though British colonization began prior to Queen Elizabeth II’s reign, Britain had an empire of more than 70 overseas territories at the time of her coronation in 1952. As a result of the brutal conditions and repression that colonial subjects endured, many colonies eventually sought independence, sometimes in the form of violent protests.

In these countries, the Queen was the head of state and not the government; hence, she had limited decision-making power. Nonetheless, as an influential political figure, the Queen had the opportunity to be vocal against colonization. On many occasions, she was silent on the subject.

“She did serve her people — and by her people, [I mean] white people. She served them, but she didn’t really serve people of colour,” said Nandini Shrotriya, a cinema and art history student.

Shrotriya is from India, which the monarchy ruled as the British Raj from 1708 until 1947.

In the British Raj, the British used a ‘divide-and-rule’ policy to create religious divides between Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, and Christians. This infighting made it easier for the British to arbitrarily divide the Indian subcontinent into two independent countries, Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India. This division became known as the Partition of India.

At the time of the partition, Pakistan was geographically divided into East and West Pakistan, with India in the middle. East Pakistan later gained independence from West Pakistan after a nine-month-long war in 1971 and became Bangladesh; West Pakistan became present-day Pakistan.

As a result of the partition, people were forced to leave their homes and migrate across the newly created border to avoid religion-based persecution and violence in their hometowns. By the time this colossal migration drew to a close, fifteen million people had moved and between one and two million people had died in the process. A long-awaited apology from Queen Elizabeth II never came during her numerous trips to the region.

As a contrasting example, Shrotriya highlighted the hands-on humanitarian work that Diana Spencer, Princess of Wales, took part in while abroad in Commonwealth countries, such as advocating against landmine use in Angola and visiting leprosy hospitals in Nepal, Zimbabwe, and India.

Though Queen Elizabeth II served as patron for more than 600 charity organizations during her lifetime, she did not participate in humanitarian work during any of her more than 100 visits abroad.

Ironically, Sutherland pointed out, the monarch’s death has dominated international media coverage; over half of the world’s population was expected to watch her funeral on September 19. Consequently, fatal natural disasters in Commonwealth member countries have gone comparatively unnoticed by the media, such as the flooding in Pakistan — which has killed more than 1,600 people so far and displaced more than 33 million people from their homes. Outside of the Commonwealth realm, Hurricane Fiona’s destruction of Puerto Rico left the entire US territory without power and killed at least 25 people.

“It’s perpetuating an inequality between these formerly colonized countries that aren’t getting that same attention,” Sutherland said about the Queen’s funeral’s large viewership.

A new conversation

Though to many, the Queen’s death may seem like the end of an era, it can also represent the beginning of a new conversation.

“The Queen’s death might be significant in that it opens up a space for former colonies to reconsider their relationship to Britain, particularly those places where the Queen is still the head of state,” explained Cecilia Morgan, a professor focusing on Canadian studies at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Closer to campus, U of T provides spaces and resources for students to think about topics such as the monarchy and colonization. In an email to The Varsity, a U of T spokesperson wrote that the university “encourage[s] students to explore the range of clubs… at the University that assess world events from a range of perspectives.” These clubs include various student associations for specific ethnicities, and groups centred on exploring the cultures of those ethnicities.

The U of T spokesperson also highlighted the university’s seven Equity Offices as a resource. For students at all campuses, U of T has an Anti-Racism & Cultural Diversity Office, which offers education, training, and complaints resolution support “on matters of race, faith and intersecting identities as guided by the Ontario Human Rights Commission.”

Moreover, there is the Office of Indigenous Initiatives that directs its efforts “towards listening, coordinating, advising and collaborating” with academic and non-academic campus communities in addressing U of T’s Calls to Action. The Calls to Action were suggested by U of T’s Truth and Reconciliation Steering Committee in 2016 as a response to the challenges outlined by Canada’s 2015 Truth and Reconciliation final report.

Additionally, UTSC and UTM have access to an Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Office on their respective campuses, which “promotes an equitable and inclusive campus community, free from discrimination or harassment based on the grounds covered by the Ontario Human Rights Code.”

If students lack the free time to access these supports, Morgan suggested that they explore U of T classes whose curriculums focus on colonization, as doing so “provides [them] with faculty who work on these questions professionally.” Morgan gave the example of U of T’s Department of History, where some professors study the histories of colonialism: “I would encourage students to consider taking courses that provide them with the opportunity to explore these questions in depth.”

Though, through colonization, the British empire left the world fragmented into colonial pieces, the aftermath of the Queen’s death offers us an opportunity to listen to criticisms of the empire that were once overpowered.

“I would like… [for this not to] become a polarizing moment,” Sutherland said. She added that she doesn’t want the Queen’s legacy to be one of a bad, or perfect, person, but for “people to come together and have deep conversations about different histories and different realities.”