From the moment I was born, doctors apologized profusely to my parents about who I was not and who they could not hope for me to be.

After already welcoming three boys, my parents were ready for a daughter to join their family. I could have come out sporting a lizard tail and 12 heads — there was never much that could have dimmed my family’s excitement over finally welcoming a baby girl. Thankfully, in the absence of any reptilian vestiges, and in spite of those doctors’ patronizing worries about the quality of my future, I was healthy. To celebrate, my dad gifted me the name that he dreamt of 15 years prior — the Arabic name “نور الهدى” that proclaimed me “the light of guidance” and is the origin of my current nickname, Huda.

This celebration ended within the week of my birth, when I was poked, prodded, scanned, weighed, and measured in the hospital. All the while, my anxious parents wished to take me home. Eventually, I was diagnosed with hemifacial microsomia (HFM), a condition in which the tissues on one side of my face are underdeveloped and do not grow normally. HFM is a manifestation of oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum disorder (OAV), a rare congenital birth defect that, in varying degrees, affects the craniofacial — head and face — bones, the eyes, the ears, and the spine.

Yes, I was born healthy. But I also happened to be born with improperly grown craniofacial structures on the left side of my face and head. This was all because of grade III microtia — a deformity of my outer ear, leaving a small remnant ear lobe — which is why doctors warned my parents when they greeted me into the world. Maybe these doctors were displeased because I had an improperly formed middle ear, no ear canal, and no outer ear. They could have been put off by the small, irregularly shaped bones that made up my left jaw, creating facial asymmetry. Perhaps they were outraged because I have congenital scoliosis, a curving of the spine, and renal dysplasia, a failing kidney, on one side. They estimated the quality of my life from what they saw outwardly: a human Toyota Prius hybrid.

My family seemed to be on an undeterred quest to prove the doctors wrong. The doctors warned that it would be likely that I would be held back in school, so I started reading by age two and took on math equations at age three. The doctors predicted that I would never excel in an artistic outlet that relied on hearing, so I played the piano and the violin, was in a handbell choir throughout elementary and junior high school, and have been a highland dancer since I was three years old.

I may not have been a child prodigy, but I was not what those doctors had reduced my future to. They had thrown me into a box that had labelled me as having a physical defect. Having a defect meant that I was defective. Being defective meant that I was wrong. Being wrong meant that I was a failure. Being a failure meant that I would never have a successful future.

I refused to be limited by the restraints of an ill-defined box. So I took away the dichotomy that seemed to dictate my life and focused on building my own sense of identity. My life was neither right nor wrong, neither good nor bad — I simply decided that it would be mine.

Not for fixing

There was no way to get to the root cause of why my body took shape the way that it did. There are no definitive causes, no defined genetic contributors or environmental exposures that are directly linked to HFM.

It’s suspected that my abnormalities manifested around the first month of my mother’s pregnancy through an unknown process that disrupted the development of my first and second pharyngeal arches. Pharyngeal arches are early embryonic structures that dictate fetal development of cartilage, bone, muscles, glands, certain organs, and the major structures of the head and the neck. Though a child can be diagnosed with OAV syndromes at birth, there are some details that doctors will not know until those children grow older. At this point, doctors can better see structural abnormalities.

In my case, many of the varying manifestations of my HFM were undetectable without close observation — with the exception of The Ear. It was a glaringly obvious issue, but, truth be told, I really liked it. It was a small ball of remnant cartilage and a flap of skin that vaguely resembled a peanut. Moreover, it became a big part of my identity. I was “the girl with one ear” and that ear became a source of inside jokes and made-up stories. It was my self identifier — as in, “Look out for The Ear,” or “We’ve always got to accommodate The Ear!”

My parents were hellbent on making sure I never felt out of place because of my differences. My appearance was never a taboo topic in my home, nor was I taught to shut down questions from curious preschool friends or their parents. I was put into dance classes early on; my hair would often be slicked back into a tight bun or ponytail and kept there at the mercy of a generous amount of hair gel. Still, I didn’t ever feel self-conscious about the exposed missing artefact from my head. I went to school boasting elaborate, pinned-up hairstyles, oblivious as to whether or not The Ear showed.

Obviously, without a properly formed ear, there was no hearing. I am Deaf, and was also mute for much of my early childhood. Instead of speaking, I relied on sign language to communicate to my parents and my best friend.

Doctors regularly offered my family and me aids to assist my hearing. When I was five, we discussed the possibility of the Bone Anchored Hearing Aid (BAHA), a device externally fixated to the skull that would allow conduction for some hearing on my left side. The doctor gave me a temporary BAHA affixed to a tight metal headband. In an effort to make it appear less bleak to a kindergartener, my mum bought ribbon and small fake flowers to decorate it.

I hated it. I don’t remember how much it did or didn’t work, but I hated it. It felt weird, and more importantly, I felt weird. While wearing it, I was self-conscious about my appearance and knew that, in some way, I was no longer myself.

Although I was young, my parents allowed me a great deal of decision-making power when it came to my body. I vetoed the BAHA, and it was never brought up again. It is a decision I have upheld until this very day.

Later, in elementary school, I tried a frequency modulation (FM) device — a tool used in conjunction with a normal hearing aid — which helped amplify sound in my good ear. Although it aided with my hearing, I felt embarrassed and scared every time I had to ask a substitute teacher, guest presenter, or other adults to use it, scared they would mock me in some way.

The truth is, I was happy being Deaf. Similar to The Ear, it was an integral part of my identity. Yes, being deaf in a hearing world that is unfit to cater to my needs means that I have a disability. Being deaf in itself, though, is a privilege.

To many, if not most, hearing people, being deaf is construed as something to be fixed. For me, however, being able to turn off one of my key senses and tune in to other sensory stimuli is a unique experience. When I could see people speak, but could not hear what they said, my imagination could run wild coming up with what they were talking about. Watching body language, facial expressions, and lip movement, I could construct the wildest of conversations in my head, and found it truly peculiar to be able to eavesdrop without hearing a thing. I think this is why I took so well to dance and music — music is about listening with your emotions, and dance is about feeling the sound.

Cochlear implants in babies, BAHAs, and FM devices — rather than being seen as the aids they are — are touted as solutions to a problem, the problem being the deafness itself. Although I don’t use sign language in my day-to-day life anymore, Deaf culture and identity are still core components of who I am. A person’s identity isn’t something that can be fixed.

A semblance of normal

Although I was resistant to procedures to restore my hearing, I had always entertained the idea of ear reconstruction. I’d maintained an obsession with human anatomy from as early as I can remember. The earliest age that I would be eligible for surgery was age 12, so I was happy to spend each year leading up to that considering such a fascinating concept. I was hooked on the idea that a piece of my body could be built from seemingly nothing.

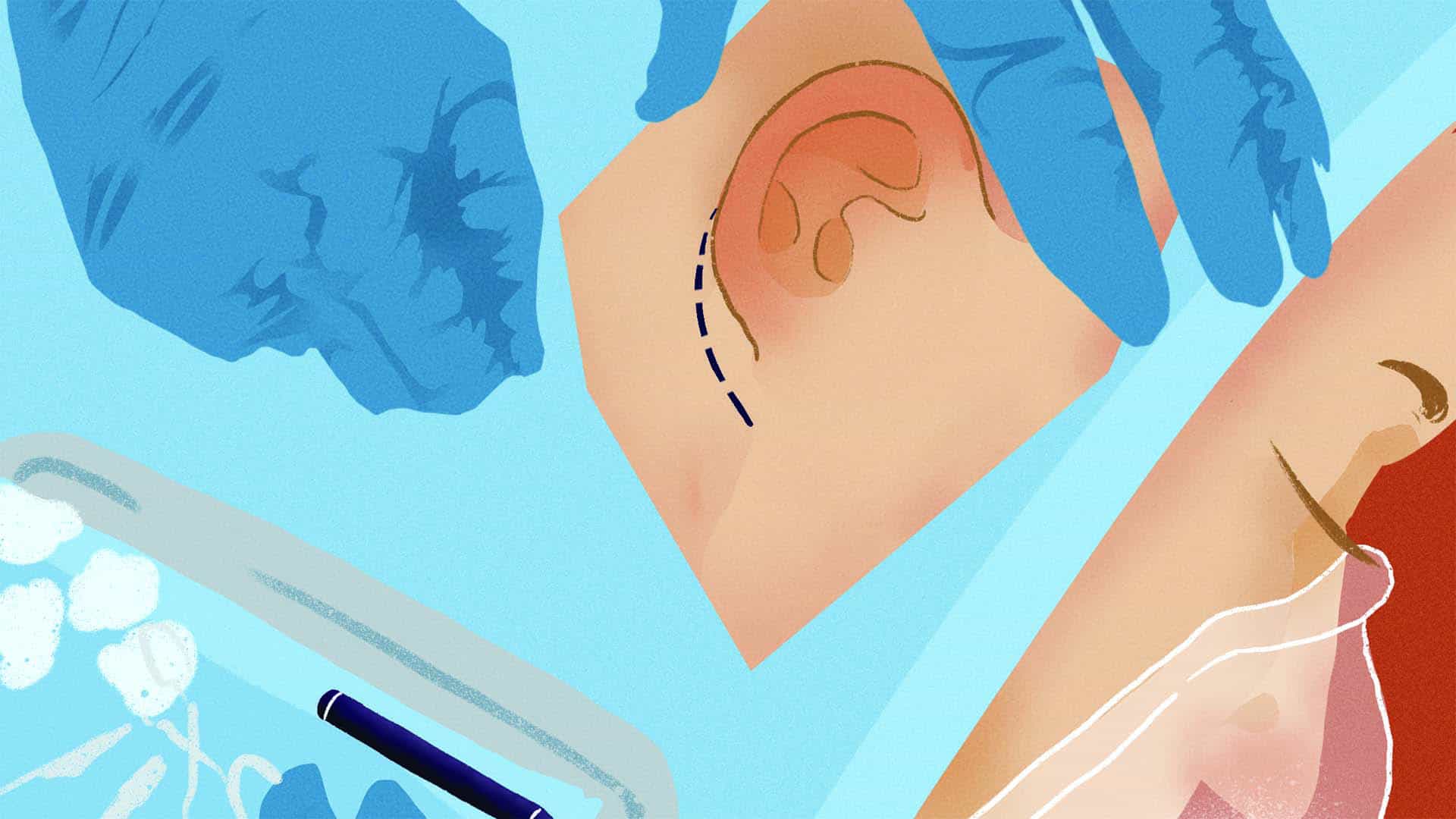

The year I was born, I became a patient at the Institute for Reconstructive Sciences in Medicine, a world-renowned clinic and research institute based out of my native Edmonton’s Misericordia Hospital. There, I continually visited my plastic surgeon, who would evaluate me for surgery and discuss hearing options with my parents. Eventually, I was prepped for the Nagata Method of Auricular Reconstruction (NMAR), which was considered to be a gold standard in reconstructive procedures in the HFM community.

NMAR uses the patient’s tissues for reconstruction rather than prosthetic materials. This is ideal because there is no chance of rejection or of the ear needing to be replaced. The procedure consists of two separate surgeries, which is fewer than other methods of reconstructive surgery.

In the first procedure, cartilage is harvested from the floating rib of the patient and carved into the shape of an ear. A pocket in the scalp is then made to host the real, fake ear. Stitches are placed to adhere the skin and cartilage, and wires are inserted to adhere the ear flush against the skull. In the second procedure, the leftover cartilage lifts the ear away from the head, giving the skin a more realistic look. It’s an artistic feat that can make even the most seasoned surgeon break a sweat.

When I entered junior high, I was finally at the age where my surgeon was comfortable proceeding with this surgery. Similar to my openness about The Ear, I was open about my decision to have reconstructive surgery. When I finally received an appointment date — April 18, 2012 — I eagerly talked about my surgery with my friends, as it seemed surreal that the moment I had spent my life preparing for had finally arrived. One conversation that I had was with my best friend, Karen, during our school’s lunch hour:

“So after the surgery, are you going to be able to hear?” Karen asked.

“No,” I replied.

“Then what does it do?”

“It gives me an ear,” I answered, hesitant as to what she was implying.

She accused me: “You’re having plastic surgery.”

I scrunched up my nose, similar to how a child would if someone offered them a matter-of-fact statement that they were reluctant to accept.

I offered an “I guess” under my breath and diverted my eyes downward.

Those words — “plastic surgery” — sounded bad. They sounded ugly, conceited. To Karen, “plastic surgery” is all it boiled down to. And so I, a newly minted teenager, came to the realization for the first time that what I had spent 13 years preparing for was just “plastic surgery.” I felt discombobulated. The Ear was a big part of my identity, and now it would be changing. This surgery would split who I was in two: me before the surgery and me after the surgery.

That night, I felt vain and disappointed in myself. I stood in front of my bedroom mirror and traced my fingers over the space where my ear would soon be. I studied my body from head to toe and asked, what’s next? Where does it end? Did I want a nose job? Boob job? Butt lift? What outcome was I truly after?

I certainly wasn’t insecure about The Ear, so the only plausible answer that I could conjure up was “a semblance of normal.” But could I be secure about who I was and still pursue surgery towards something else, something that I perceived as normal?

A guiding light

This past April, I celebrated the 10th anniversary of receiving a new ear. While I can’t travel back in time to assure myself that I made the right decision, I can bring all my knowledge into my upcoming jaw surgery and enter it with a little more confidence than I once had.

For a while, I was hesitant to go forward with further surgeries. Plastic surgery represents an often inaccessible realm in health care that is associated with privileged socio-economic status, or someone who is vain. But plastic surgery is also for reconstructive procedures for patients with birth defects such as myself; it’s nose jobs to assist with breathing; it’s reconstructing body parts after bodily trauma or cancer; it’s burn care; it’s cleft lip and cleft palate repairs; and it’s gender-affirming care. Most importantly, it’s an integral part of health care and plays a role in moving towards the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals — one of which aims to promote healthy lives and wellbeing for people of all ages.

This revelation reinstated the confidence that I had lost and reassured me that there was nothing wrong with going through with the procedure. The decision-making powers that my parents granted me growing up were not something commonly seen, particularly for children. So, when the opportunity came along to create change from sharing my story, I knew I wanted to take it.

I approached the team for the Craniofacial Microsomia Accelerating Research and Education (CARE) study at Seattle Children’s Hospital in the spring. The study seeks to learn about the lived experiences of the CFM and HFM communities, their families, their health-care teams, researchers, patient advocacy groups, education systems, policy makers, and members of the public. The hope is that, by learning more about CFM from varying perspectives, the overall wellbeing, access to care, and educational resources available to patients and their community will be greatly improved to best reflect their unique needs.

Perhaps, by assisting with this study, I can live up to my namesake. Perhaps, to someone somewhere, I can be a “light of guidance.”