Content warning: This article discusses death, casualties, and other impacts of catastrophic floods in Pakistan.

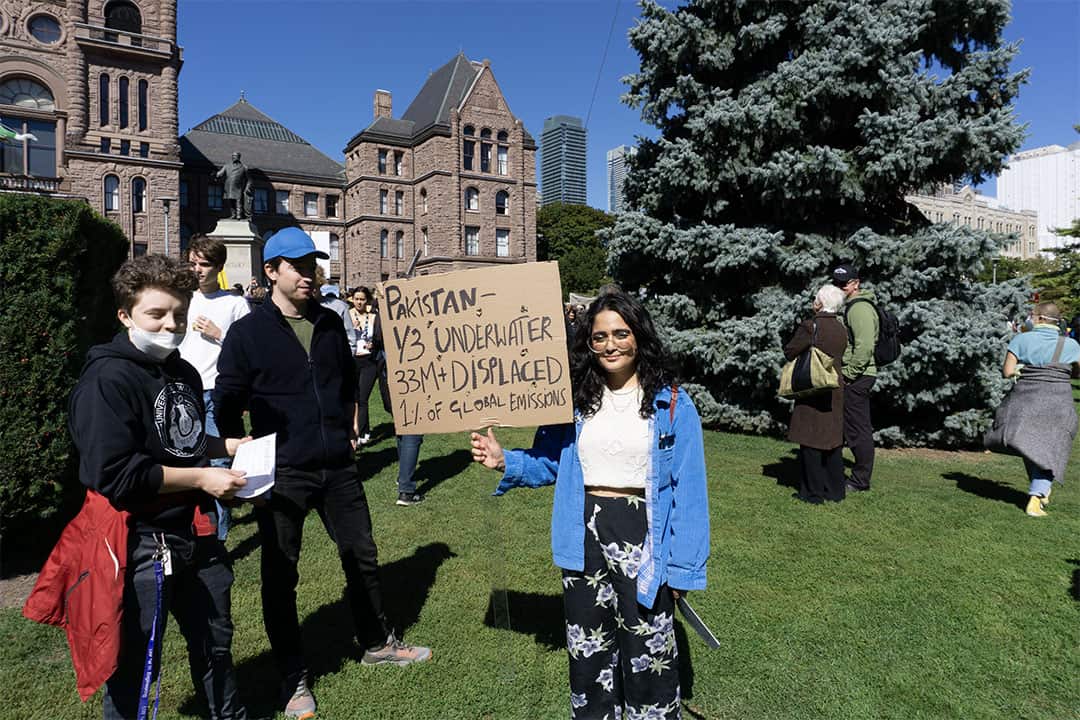

As of October 14, over 1,700 people have died from the catastrophic floods in Pakistan. In August, Pakistan’s Climate Minister Sherry Rehman reported that one-third of the country was underwater. Earlier this month, Bloomberg reported that around 21 million Pakistanis are in “desperate need” of help.

As these catastrophic floods continue to impact millions in Pakistan, The Varsity talked to U of T students whose families have been impacted by these floods. They stressed that U of T professors and administration need to acknowledge the floods and recognize their impact on Pakistani students’ mental health and well-being.

Background

The areas most badly affected by the floods are in the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan. HIstorically, these areas were underfunded by the federal and provincial governments.

Pakistan received three times the normal amount of rainfall in August for monsoon season. According to World Weather Attribution researchers, “climate change likely increased extreme monsoon rainfall” in Pakistan. The massive increase in rainfall came after an uncharacteristically hot summer for Pakistan. Jacobabad, a city in Sindh, was declared the hottest city on Earth this summer, with temperatures exceeding the survivable range.

Factors like inadequate infrastructure and river management systems, high poverty rates, gender disparities, and ongoing political and economic instability further exacerbated the impacts of the flooding. For instance, a summer heatwave that melted Shisper Glacier contributed to the collapse of a bridge in Swat, a popular tourist destination in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. For many, the floods destroyed their only source of income, increasing the disaster’s impact.

Impact of the floods

Filzah Panhwar, an undergraduate student at Woodsworth College majoring in women and gender studies, is from the Pakistani province of Sindh. Her relatives reside in Dadu, a city in inner Sindh.

Panhwar told The Varsity that her aunt, a survivor of stage four breast cancer, hasn’t been able to access treatment. She needs to travel to Karachi since cancer treatment is not available in her city, but she can’t travel from Dadu to Karachi because roads remain underwater.

Talking about the scale of destruction in Sindh, Panhwar said, “We’ve never seen something like this.”

Panhwar also stressed the importance of evacuation alarm systems, which could have saved lives by notifying people when they needed to evacuate. She told The Varsity that in Dadu, only the rich neighbourhoods were informed about the need for evacuation; most people didn’t know that their lives were in danger until the floodwater reached their villages and homes.

Panhwar also mentioned ways in which patriarchy plays into the dynamics of humanitarian aid for affected people. She said that it is unlikely to find a woman in line at a relief camp, because if a woman asks for aid at any such camps, “the first question they will be asked is ‘where’s your husband or your father or your brother? Why are you here? Where are they?’ ”

Sarah Rana, an undergraduate student in contemporary Asian studies and vice-president, equity of the University of Toronto Students’ Union, also has family in Pakistan. Rana’s relatives live in Jhelum, a city in the province of Punjab that is situated on a riverbank. Rana said that her family was asked to evacuate because of the rising water levels.

Some of Rana’s other relatives live in Swat. She said that Swat was “basically destroyed” by the floods, and her relatives’ small business — their only source of livelihood — didn’t survive.

Economic and political context

When the floods hit Pakistan, the country was already grappling with political and economic turmoil. Former Prime Minister Imran Khan was ousted in April, and the country’s economic situation has continued to deteriorate since then. In April, the Pakistani rupee exchange rate was 182 rupees to one USD. Soon after, the value of the rupee decreased, with the exchange rate rising to 240 rupees per USD. As of October 23, one USD equals 219 rupees. In June, The Times of India reported that Pakistan was on the brink of bankruptcy, with “no immediate positive outlook.”

Since then, floods have destroyed a significant proportion of the country’s cash crops, including around 45 per cent of the country’s cotton. As an agricultural country, Pakistan relies on cotton and rice exports as its main source of income. With the economic catastrophe exacerbated, it’s unclear if Pakistan can invest the huge amounts of money needed to restore infrastructure and people’s livelihoods in the affected regions.

Why was the flood so catastrophic?

In an interview with The Varsity, Romila Verma, a sessional lecturer in the Department of Geography & Planning at U of T, explained why Pakistan has been so adversely impacted by the floods.

Verma mentioned that, at the time of the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent in 1947, the British divided the Indus river between India and Pakistan, with the riverhead starting from India. The country where the riverhead starts gets to decide the water flow, which has been the source of major contention between Pakistan and India over the decades. Despite the Indus Waters Treaty signed between India and Pakistan, which allocates three rivers to Pakistan and three to India and gives each country certain rights over the other’s rivers, the Pakistani river system needs robust management to avoid severe droughts and flooding.

Additionally, Verma said that Pakistan’s geographical location at the foothills of the Himalayas makes it prone to large flows of water. Pakistan is also home to the highest number of glaciers in the world, which have started melting as a result of global warming. She stressed that the country needs robust management systems to deal with these large volumes of water, but Pakistan has not developed such systems so far.

Pakistan has seen large-scale floods before as well. In 2010, massive flooding caused the death of over 1,700 people and displaced over 20 million. As Verma told The Varsity, the country hasn’t improved its flood management systems since then.

“If you don’t learn from history, as they say, you’re condemned to repeat it,” she said.

Need for more attention

Rana expressed her disappointment at the lack of recognition of the Pakistan floods by the U of T administration and Western media. “I felt really helpless,” she told The Varsity.

Emphasizing the need for professors and university administration to recognize the impact of floods in Pakistan, Rana said, “there are a lot of students [at] U of T who are literally watching their home get destroyed.”

In an email to The Varsity, a U of T spokesperson wrote, “We recognize that members of the University of Toronto community may be affected by these traumatic and tragic events and other global events, and offer a range of resources and supports for students, faculty, staff and librarians.” They listed a number of resources around campus for mental health and academic support.

Rana said that professors need to be mindful of students whose families may be impacted by floods and show leniency regarding deadlines. She further added that those affected in Pakistan need financial aid and that people in Canada should donate as much as they can.

Panhwar also stressed the importance of global attention toward the situation in Pakistan. She compared the floods to war, saying, “there needs to be a lot more buzz around what’s happening in Pakistan… On a humanitarian level, it’s no less than a war.”

If you or someone you know is affected by the ongoing situation in Pakistan, you can contact:

- Across Boundaries — a support service for racialized people that offers support in various languages including Urdu and Punjabi — at (416) 787-3007,

- Bean Bag Chat through their mobile application for service in Toronto,

- Distress Centres of Greater Toronto at (416) 408-4357,

- Gerstein Crisis Centre’s 24 hour-crisis line at (416) 929-5200,

- Good2Talk at (866) 925-5454 — available 24/7,

- Here 24/7 at (844) 437-3247,

- Naseeha Mental Health — confidential helpline for young Muslims — at (866) 627-3342, or

- U of T My Student Support Program — available 24/7 — at (844) 451-9700.

See mentalhealth.utoronto.ca for more resources.