Content warning: This article discusses misogyny and contains detailed descriptions of violence and sexualized violence against women.

For decades, slasher flicks have delighted audiences with their neverending spectacular extremities. Although every slasher is the same, in that there’s always a sophisticated killer and someone eventually dies, the subgenre has managed to fill out theatres with every new release.

Wes Craven’s 1994 classic Scream was the first meta movie to identify and satirize this predictability. In a hilariously self-aware scene, Randy Meek explains the infamous laws of surviving a horror film. His three simple rules — no sex, drugs, or wandering off — are ruthlessly accurate, exposing the slasher subgenre’s formulaic tendencies.

But I question whether Randy’s golden tenets hold true for both men and women. Indeed, both genders are punished for committing the same groan-inducing mistakes. But whereas the man tends to be killed in an unassuming way, the woman is always disproportionately punished for her crimes.

I am not surprised that the woman slasher victim endures this misogyny-tinged fate. Look no further than at Hollywood’s top boogeymen, a lineup of iconic figures such as Micheal Myers, John Neville, and Norman Bates. Many, if not all, are men embroiled in sinister relationships with the opposite gender. Among the ranks are lecherous sadists who can only ‘finish’ to the bloodied female death. Others are intrepid, sickly frail outcasts motivated by their torturous oedipal complexes. In all cases, one thing is certain: cinema’s murderous superstars have always wielded rusted knives and twisted feelings toward women.

Even in films like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), in which our killer’s motive is unclear and does not appear to have a basis in gender, the camera has an obscene fixation on women. Consider the back-to-back murders of Kirk and Pam. Kirk is bashed once with a sledgehammer; but before we can process, the camera pulls so far back that his silhouette is submerged by shadows. It is a swift, private, and absolutely forgettable snuffing.

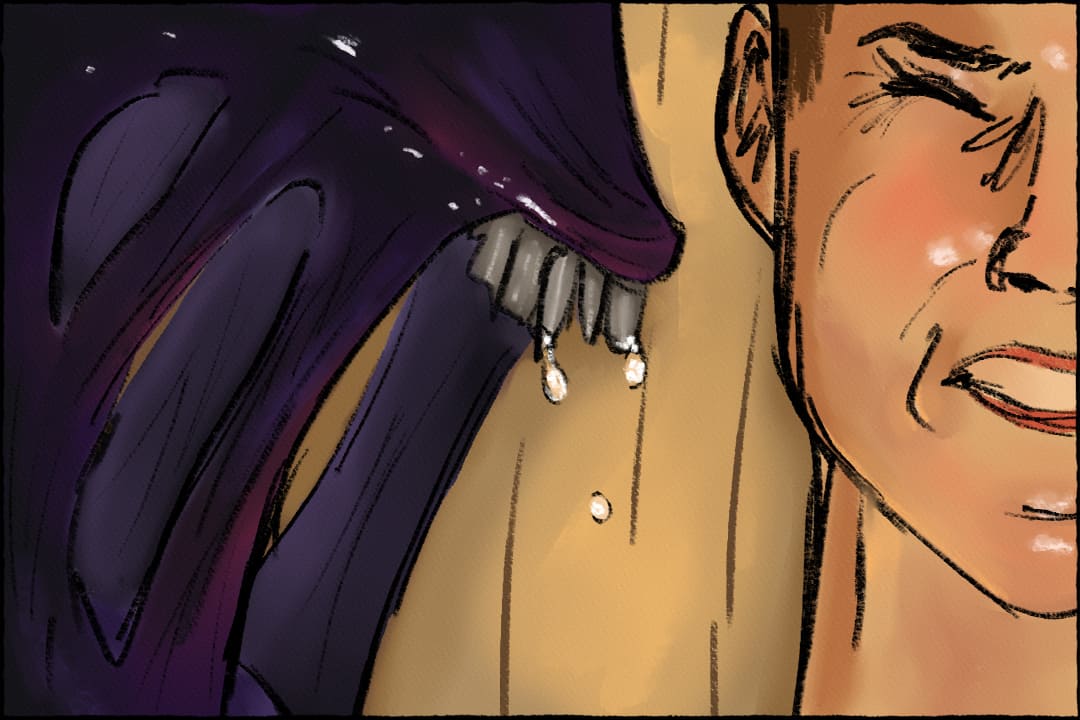

On the other hand, Pam’s death is etched into our cultural consciousness. The iconic scene begins when Leatherface abruptly yanks her into hell’s house. The camera sticks close to Pam’s resistant, flailing body, tracking her every feral attempt to wrestle out of his tenacious grip. But it’s no use; she is impaled by a meathook. We cut yet again, situating us so uncomfortably close to Pam’s face. Her every muscle contorts in agony, a horrific sight paired with her equally harrowing, discordant screams. This is macabre manifest.

The difference between Kirk and Pam’s deaths is just one example of the gender discrepancy in framing. Every slasher formally unfolds the same way. The man victim’s death is always lackluster: attacked with a knife or, in Kirk’s case, a hammer to the head. It is almost as if he’s being skimmed over, an hors d’oeuvre served to placate our blood-lusting appetites until the main course.

If he is the starter, then she is the Michelin meal. The camera takes its time with the woman; narrowing on her expressions, twitching limbs and bouncing buttocks. In a cruel yet spectacular frenzy, she is attacked until every drop of terror is wrung from her ravaged body. Broken yet still beautiful, her taxidermied image lingers across the scene before we cut to our next unfortunate prey.

All this suggests that sinister logic underscores the slasher film. From killers with specifically gendered motives to the sensationalized focus on her death, there exists a gauche fetish for the slain female figure. She is the film’s corpus; her teased-out and dramatic slaying are essential. This is what anchors the slasher.

But why? Why does an entire genre revolve around the terrorized woman, and what does that say about us? What is it about the abject feminine ‘scream’ that keeps us wanting more, so much so that an entire industry has been built on our sick fascination?

Sex and slashers

In her seminal text Men, Women and Chainsaw: Gender in the Modern, Carol Clover suggests that horror and pornography are distinct from the remaining genre basket. Unlike other genres, their end goal isn’t to appeal to the cerebral sensibilities but to evoke our most primitive human senses. Watching either, we flush with anticipation, breathe in hitched dashes, and shake with each pounding heartbeat. We are invited to feel, to metabolize, and to react. Horror cinema and pornography, therefore, share the same phenomenological approach toward the sensate.

Slashers combine both fear and sex to maximize the spectator’s corporeal experience. In its tamest manifestations, narratives will include unnecessary shots of undressed women or fixate on their fleshy parts. Hot and heavy scenes are frequently interpolated with a looming dark presence. The most salacious synthesis, however, occurs when sex is entwined with the process of murder.

Consider the all too common scenario: a gorgeous Pamela Anderson type runs through the woods, her DD breasts flailing in full glory, before being viciously borne down by her masked killer. He thrusts his phallic weapon into her, going harder and faster each time. She hysterically screams, moans, twists and turns before gurgling orgasmically to death. To state the obvious, the killings are often thinly veiled allegories for sex, designed to stimulate complete viewing arousal.

We can think of this entwinement in terms of Laura Mulvey’s all-too-familiar essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In it, Mulvey argues that women are seen as threats to the patriarchal order due to their de facto sexual difference. Men cope by looking at women through a voyeuristic and fetishistic manner, thereby suppressing her perceived power to disrupt women’s equilibrium. Cinema, Mulvey argues, is a tangible materialization of this male anxiety; so when the camera frames women, it acts in accordance with the male gaze. Men, and sometimes even women, then identify with this subconscious logic.

The slasher’s emphasis on fear and eros are perfect examples of Mulvey and Clover’s theories. Its crude, carnal depictions of women are designed to excite the primordial desires, to evoke a complete bodily thrill. Yet, simultaneously, her sadistic death satisfies the neurotic needs of the male ego; because her suppression reaffirms his control over the sexual world.

This discussion sketches a contour for understanding why slashers disproportionately target women and retain, if not fuel, box office demand. Simply put: it’s pleasurable. The slasher movie is designed to gratify every hedonistic sense. Viewers are at once being teased by a highly aestheticized, feminized fear and, for the mostly male audience, empowered in their gendered superiority. No wonder we’ve been seduced by the genre.

Being reflexive

As a huge slasher fan and a feminist, I realize that I may have dug myself a bottomless hole and voluntarily jumped into it. Recognizing these problematic tendencies has left a bitter aftertaste that I just cannot rinse out. My old comfort movies, Halloween and Slumber Party Massacre, just don’t thrill me the same way when I can finally see how objectified the ‘second sex’ is.

On the bright side, there’s been a strong tide among modern filmmakers to destroy the current paradigm. Films such as Inside and Bodies, Bodies, Bodies have appropriated the genre with a unique feminist spin, in turn increasing the percentage of women spectators. As audiences affect filmmaking, this oceanic change has significant implications for how women are to be depicted on screen; and, subsequently, the future rules for surviving horror.