One late evening in May 2020, my family huddled together in front of the TV as the first wave of protests, catalyzed by the brutal killing of George Floyd, swept across the United States.

The phrase that ricocheted off the streets and across social media — “Black Lives Matter” — was simple. Yet, implicit in the three words was a pressing call to action: acknowledge the racist underpinnings of the modern western state that is inherently averse to Black life, defund and abolish the institutions maintaining its violence, and enact widespread systemic reform to end racial injustice.

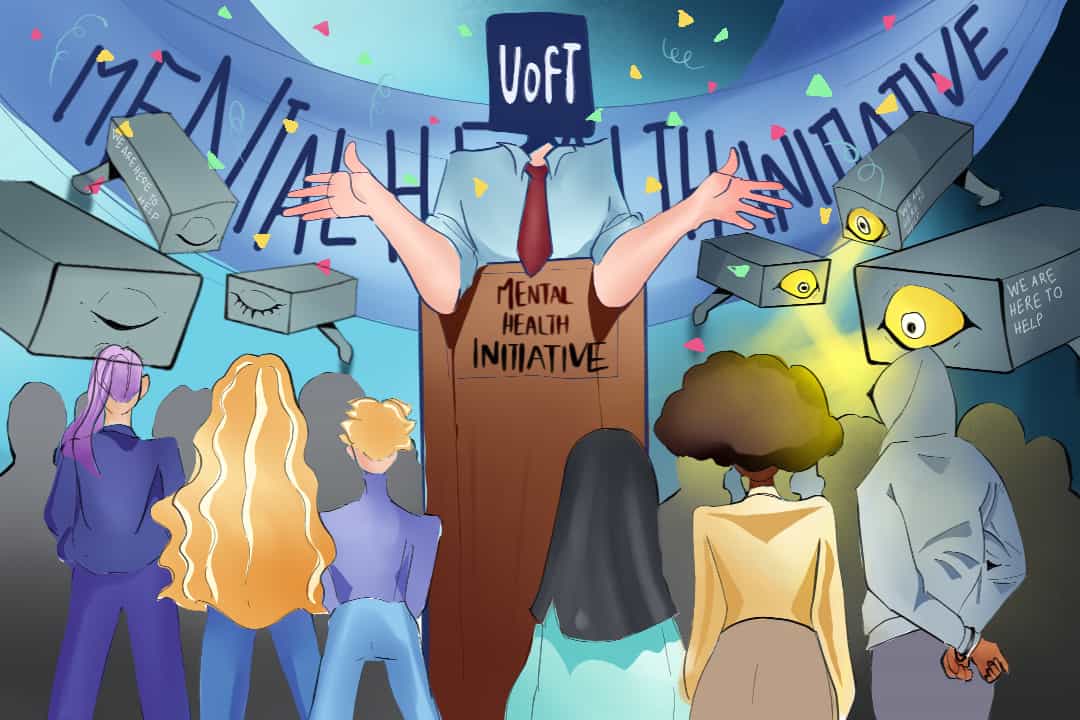

So when the University of Toronto signalled its intention to reevaluate institutional responses to mental health concerns in early 2021, there was cause to be hopeful.

This October, the U of T administration concluded that it will be amending how campus safety personnel respond to students experiencing mental health crises across all U of T campuses. Among other changes is a commitment to “[deepening] integration of equity, diversity, inclusion and anti-racism competencies and mental health knowledges” in training for Campus Safety Special Constable Service staff — who, up until August of 2021, self-identified as University of Toronto Campus Police.

Despite the name change, U of T special constables on campus continue to enjoy the same privileges bestowed upon police officers. Managed by Toronto Police Services, U of T special constables handle criminal offences at their discretion, remaining well within their rights to arrest, search, and release students.

And so, here I rekindle the argument that spawned the 2020 uprising and countless movements before it: any model based on policing — no matter how prettily packaged under promises of equity and sensitivity — is bound to disproportionately harm people of colour, particularly those from Black and Indigenous communities who bear the brunt of police violence.

In 2019, a third-year UTM student sought help from the Health and Counselling Centre for her suicidal ideations, only to be arrested by campus police. More recently, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health has found evidence of students at multiple Ontario universities being restrained by police during mental health crises.

These incidents of hyper policing — while themselves not racially significant — are inseparable from the institution’s history of serving the interests of the white settler-colonial state we call Canada. Given stories of campus police instigating or abetting discrimination against Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) individuals, it’s clear that when the criminalization of mental health converges with racialized status, it will be students of colour experiencing mental disability who pay the price.

The point I hope to make is that we cannot chant ‘abolish the police’ at Christie Pits Park for 29-year-old Regis Korchinski-Paquet — who died in 2021 after police arrived at her home — then sit idly as racialized students struggling with mental health, criminalized by virtue of existing, are subjected to initiatives that cement police presence on campus.

With Black Torontonians being 230 per cent more likely than whites to have an officer’s gun pointed at them — and other racialized groups being similarly overrepresented in instances of police force — the privilege of publicly experiencing mental crises without the threat of losing one’s life is not equally granted to all. BIPOC students cannot afford to abandon long internalized fears of police simply because special constables briefly underwent diversity training, the results of which are arguably immeasurable.

There is no deeper cut than watching a police system be refashioned for public friendliness when BIPOC students are already overwhelmingly underresourced in terms of social support. To place special constables at the crux of mental health-care emergencies as first responders suggests an unwillingness to invest in student needs and reinforces stigmatization of racialized people with mental disabilities by further associating them with crime and risk. In some circles, we’d call this institutional neglect. In others, we call it systemic violence.

To be truly antiracist, let us begin by divesting from campus policing. Let’s address the intersecting factors that underlie students’ mental health crises. Let’s open up scholarships and aid programs to ease financial burdens, normalize flexible and asynchronous learning options to accommodate different needs, and expand cultural resources to fortify students’ sense of belonging.

Let’s strengthen community partnerships so survivors of violence find resources and shelter. Let’s design courses based on compassion, entrench unlimited CR/NCR — without a deadline — and facilitate access to career counselling to fuel student success. Let’s increase funding for extracurricular clubs and programs, and establish peer-facilitated social and psychological support networks to promote socialization and collective well-being. Let’s simultaneously centre the underprivileged communities which have historically needed it most.

We cannot expect to apply band-aid solutions that ignore the wider structural inequities underlying our institutions and hope that they will naturally translate into favourable outcomes for all. It is impossible to simply “diversity train” the deeply flawed police system into perfection when its existence and unchecked power themselves sit at the root of many BIPOC communities’ intergenerational traumas. Rather than a depoliticized solution that seeks to blindly amalgamate racialized communities with more privileged groups, BIPOC students deserve approaches to mental health care that are specifically tailored to their concerns, histories, and social realities.

We have consistently ranked among the world’s best universities in terms of research, innovation, and influence. If anyone can spearhead institutional change away from carceral care toward community-based reconciliation, it’s us. The best time to do so has passed, long before the first protest erupted in 2020. The second best time will always be now.

Noshin Talukdar is a fourth-year student at Victoria College. She is the equity columnist for The Varsity’s Comment section.