Content warning: This article discusses suicide.

Canada, and much of the world, is in the grips of a mental health crisis, with a staggering 450 million people in the world currently struggling with mental illness; one person dies by suicide every 40 seconds. Having suffered nearly three full years of COVID-19 and its repercussions — including losses of family and friends, the distance from social circles and regular activities, and the emergence of crippling health anxiety — people all over the world are learning to handle an unprecedented crisis that has gotten out of hand.

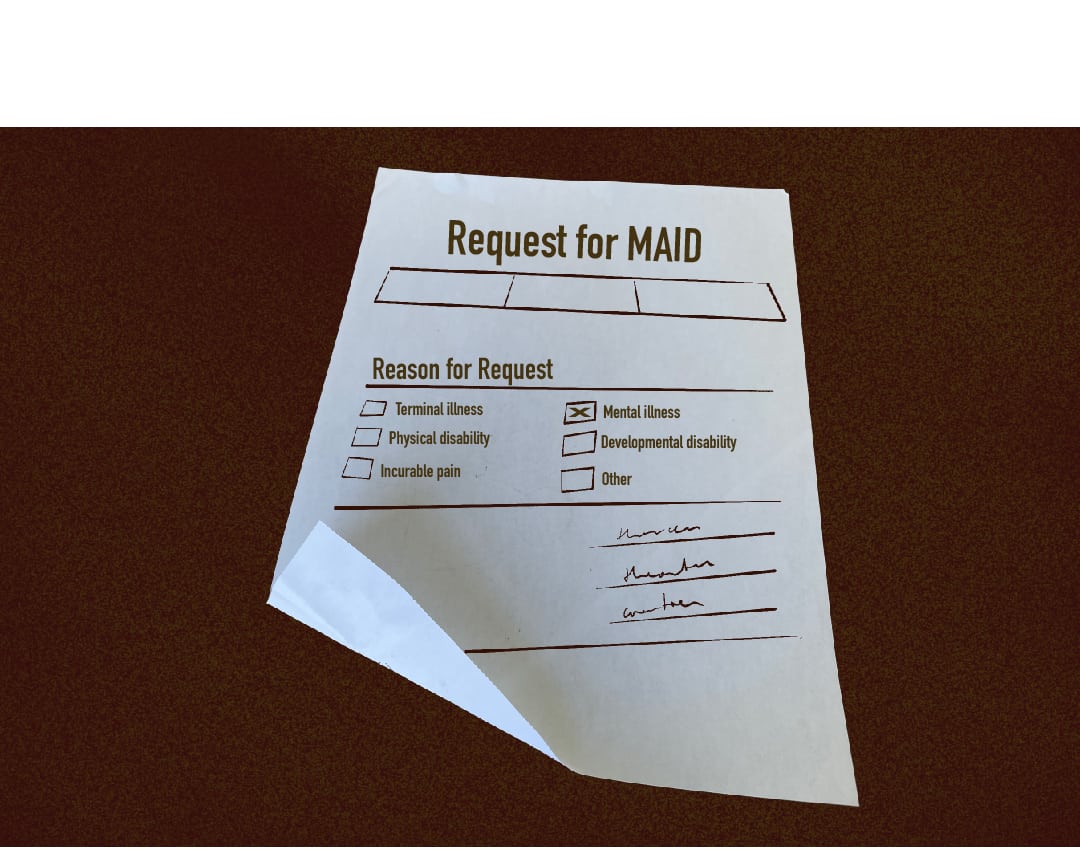

In light of this, Canada’s government has recently put forward an amendment to the assisted suicide program, known as medical assistance in dying (MAID). This program came into the public consciousness following a statement to parliament from a representative of the medical regulator committee arguing that sick children between the ages of 14 and 17 — both with terminal and non terminal illnesses — should be allowed to choose to die by suicide with medical assistance. The parliamentary committee’s response agreed that access to euthanasia should be expanded to include even more people.

To this, one may ask — how many more?

When Canada made euthanasia legal in 2016, medical professionals and media conjectured that the Canadian government would expand eligibility beyond the initial group of people with terminal illnesses, as has occurred in nearly every country where euthanasia has been made legal. The trajectory toward this, which encapsulated varied groups of patients both terminally and non terminally ill, might have been foreseen in 2015 when the Supreme Court of Canada dismissed the criminal prohibition on suicide assistance. The Court previously had legal repercussions for physicians and stated that no person is entitled to consent to their assisted death.

Quickly following this, there was a ruling from a Quebec court decreeing that restricting euthanasia to only those whose deaths were “reasonably foreseeable” was discriminating against those who weren’t terminally ill — with a statement from Phillippe Simard, delegate on political affairs in Fédération Médicale Étudiante du Québec (FMEQ), which highlighted that “those who truly wish to leave us may choose to do so at the moment that is right for them.”

Fast forward to today, and we hear conversations in medical communities around the world surrounding euthanasia legislations and its availability expansion that could result in the permitted euthanization of people with physical or mental disabilities. Perhaps even more controversial is a ruling that takes effect later this year, in which mental illnesses will become qualifying conditions for euthanasia when an individual turns 18. According to a statement released by the Government of Canada, “After March 17, 2023, people with a mental illness as their sole underlying medical condition will have access to MAID if they meet all of the eligibility requirements.” Since many mental conditions center on symptoms of suicidal thoughts out of the sufferer’s control, it seems counterintuitive that the waitlist to see a registered psychologist in many places is longer than the process to apply to die.

Perhaps with an even more shocking stance, Dying With Dignity Canada, a national human rights charity, has asked parliament to reduce the current age requirement of 18 and extend eligibility to individuals “at least 12 years of age and capable of making decisions with respect to their health.”

A child at the age of 12 cannot do most things considered ‘mature.’ They cannot vote, drink or drive, get a tattoo, or be legally married. Yet, despite these rules, a child may be able to decide if they want to die before their 13th birthday. Children nowadays have already been given more credit for their maturity and personal jurisdiction, with important decisions being given to them as solely theirs to make. Take vaccination as a current and prevalent example during this pandemic, where children over the age of 12 were told that their parents do not get to choose for them if they get the vaccine or not — it is their choice with the motivations of protecting themselves and their loved ones.

Jennifer Gibson, the director and Sun Life Financial chair in bioethics at the University of Toronto and co-chair of the Council of Canadian Academies’ expert panel of medical assistance in dying, chaired the working group on advance requests for MAID and had some light to shed on the matter. In an interview at the Justice and Human Rights Committee, Gibson contended that “with the benefit of almost five years’ experience, we have learned that MAID can be provided safely and compassionately to Canadians.”

The interview questioned her on the program, and the decisions behind the eligibility and optimal effectiveness of MAID, to which Gibson responded with questions: “Would it displace palliative care? Would it make people more vulnerable and not less?” Answering these questions is an important step in defining who should be eligible for MAID and what the ultimate goals of the program should be.

Much of the literature you can read in today’s climate is riddled with frightening statistics about mental health, the repercussions of COVID-19, and other social quandaries. One in four young individuals who spent some part of their adolescence during the COVID-19 pandemic now has some form of mental health concern, a severe increase from one in six in just one year.

Reportedly, children have suffered immensely, with UK National Health Service Digital data revealing that 19.7 per cent of boys and 10.5 per cent of girls aged seven to ten are now suffering from psychological distress. Further, the same data shows that over 25.7 per cent of youths aged 17 to 19 now have a “probable mental disorder” — up from 17.4 per cent in a year. The mental health disorders ranged from anxiety, depression, and conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder to eating disorders and psychotic experiences.

Given these statistics, one is forced to reconcile with the notion that adolescents all over the world are suffering deeply, more than we have ever known in the past, and one could argue that youths have had to grow up faster. However, is it still reasonable to give decisions, such as taking one’s life, to the youth, forcing them to see the world through mature lenses before they can even drive a car?

MAID might become the biggest existential threat from the medical community to people with mental or physical disabilities.