“New year, new me.”

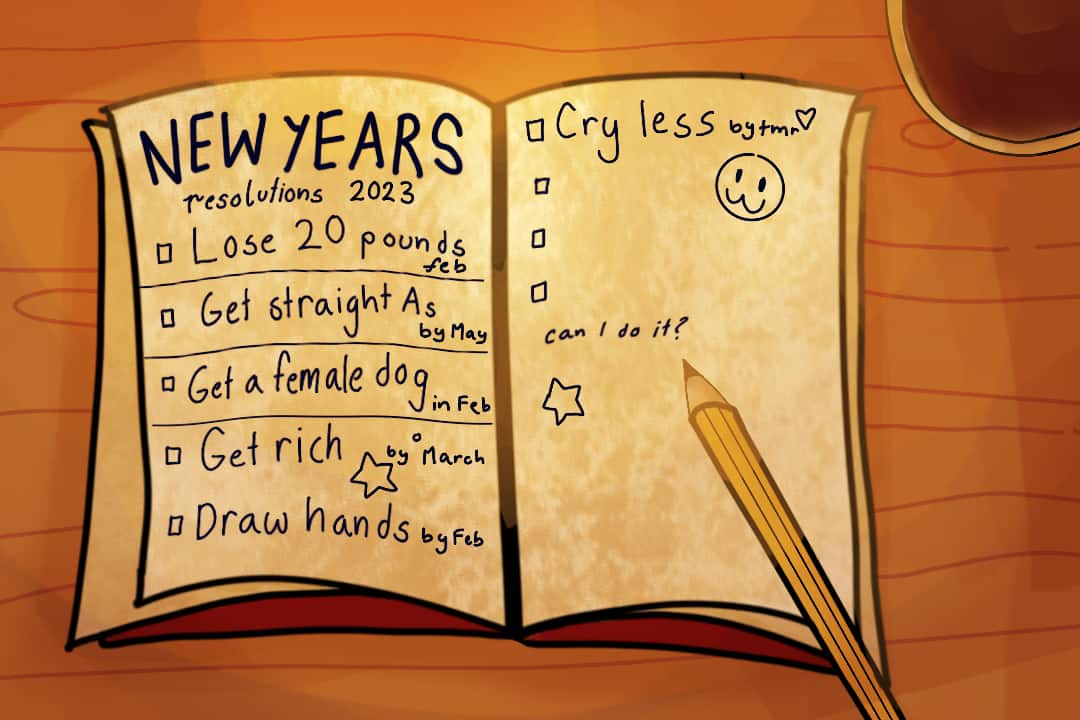

Despite the phrase’s ludicrousness, all of us get a little hopeful at that stroke of midnight, conjuring up images of what could be, and start to stake out our next course of action.

You may write your New Year’s resolutions down in hopes of manifestation, or keep a mental note; yet, about 80 per cent of us will fail to stick to these goals past a month or two. Only eight per cent of people will have stuck it through as the year finishes.

I’ve been a part of the 80 per cent. Despite the numerous planners and calendars — and I’ve even tried gamification — my New Year’s goals would always inevitably fall through. You’d think as a third-year psychology student I should already have it all figured out. But this year, you might be able to figure it out before you become part of the 80 per cent.

Why do we set goals?

Before learning how to achieve our goals, let’s think about why we even set goals. What motivates motivation?

Our goals are a reflection of our needs. In his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation,” American psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed that humans are motivated to fulfill their basic needs before those for one’s higher self. Despite a lack of conclusive evidence for its validity, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs highlights the diverse needs humans have: physiological, safety, belonging and love, esteem, and self-actualization. Our goals — working out, making time for loved ones, travelling, and more — are ideas of how to fulfill our needs.

Consequently, our brains regard setting goals as similar to achieving our needs. A 2019 study published in Nature found that the neurotransmitter dopamine — often regarded as the “feel-good” hormone — spikes not only when we’re close to achieving a goal but also when we set a goal, motivating us to take action.

When we set a goal, we tend to imagine ourselves achieving it, and visualizing this scenario can activate the same regions in your brain as physically experiencing it. Visualization can promote neuroplasticity — the formation and strengthening of pathways in your brain — which in turn can lead to reduced stress, improved performance, and thereby more motivation.

New Year’s resolutions in particular are made as we look back at what choices we’ve made and speculate what we’d like to be for the next revolution around the sun. In a 2014 study published in the journal Management Science, the “fresh starter effect” was proposed as an explanation for why events like New Year’s or birthdays are associated with increased motivation. As a “temporal landmark,” New Year’s allows people to believe their past self to be responsible for previous failures and to start anew.

What can we do to succeed?

While setting goals can increase our motivation, that alone cannot work; sooner or later, our motivation declines and we revert to our old selves. Every time I’d stop working on my goals, I’d come to see myself as characteristically undisciplined. Consistency, I’d believe, just wasn’t my strong suit.

So, do we, the 80 per cent, fail to achieve our goals simply because we’re undisciplined? James Clear, the author of Atomic Habits, says otherwise. In his book, he explains that disciplined people don’t necessarily have more willpower, they just surround themselves with fewer temptations.

While setting goals — even SMART goals — is a good first step to enact actual changes, we need strategic plans. Taking from the operant conditioning model, a psychological paradigm for learning using rewards or punishments to modify behaviour. Clear outlines a four-step model to improve our habits. By making good habits obvious, attractive, easy, and satisfying — and conversely, by making bad habits the opposite — Clear posits that we’d be well on our way to achieving our goals.

While his habit cheat sheet describes plenty of practical strategies, there are two main things to keep in mind: situation change and slow-but-long-lasting progress.

To keep temptations at bay, we can design our environment to be free of distractions. Keep what you want in plain sight and what you need to avoid somewhere inconvenient. Furthermore, by joining groups with similar goals or having people who can keep you accountable, you increase your likelihood of success. A 2022 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that between two groups of students — one whose professor instructed them to create personal plans to not use technology in class and the other whose professor established a social norm — the latter reduced their technology by far more. Our primal desire to fit in and belong means we’ll often adopt the habits praised and approved by others, so choose your circles wisely.

Lastly, habit formation takes a long time.

For my fellow perfectionists, Clear writes, “Instead of trying to engineer a perfect habit from the start, do the easy thing on a more consistent basis. You have to standardize before you can optimize.” The easier an activity, the more you’ll repeat it. And the more you repeat it, the stronger the connections between neurons for the particular activity become — neuroscientists call this long-term potentiation. These small changes in the brain will compound, making the activity more automatic, and eventually, you’ll find yourself consistently enduring the more difficult activity.

New year, new habits, new me

Everything comes down to identity. When we set goals, we’re testing our self-efficacy — a psychological concept coined by psychologist Albert Bandura, referring to an “individual’s belief in his or her capacity to execute behaviours necessary to produce specific performance attainments.” Our goals are integrated into our self-image and must be met to keep our self-image intact.

At some point, we no longer think of ourselves as ‘writing’ or ‘procrastinating,’ but as a ‘writer’ or a ‘procrastinator.’ A 2019 study found that our habits serve to define us and that when habits are in line with our feeling of identity, this comes with stronger cognitive self-integration, higher self-esteem, and a striving toward an ideal self. After setting goals and making incentives, identity is what sustains a habit.

So next time you or a friend says “new year, new me” ironically, add in “new habits” there and see if it makes a difference.