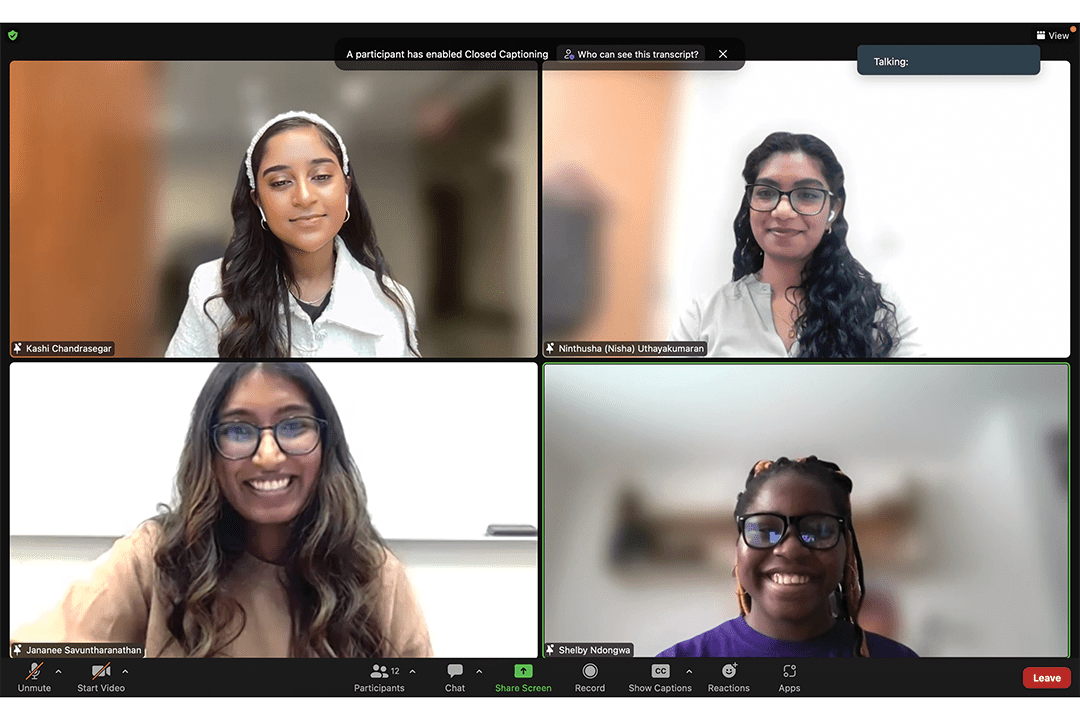

January marks Tamil Heritage Month, and, on January 25, the UTSC International Student Centre, St. George Centre for International Experience, and UTM International Education Centre collaboratively hosted a panel discussion featuring three Tamil members of the U of T community.

The panellists discussed connecting to their Tamil heritage, navigating misinformation about their identity, and cultivating a sense of community at U of T.

Stories

The Tamil people are an ethnic group primarily made up of Tamil-language speakers in southern India, Sri Lanka, and throughout South Asia. Many Tamil people practice Hinduism, although the community also includes Jains, Christians, and Muslims.

Panellists Ninthusha Uthayakumaran, Jananee Savuntharanathan, and Pirakasini Chandrasegar were all born and raised in Canada. Their parents left Sri Lanka as a consequence of the Tamil genocide during the Sri Lankan Civil War, which lasted from 1983–2009.

Although some Tamils arrived in Sri Lanka before 500 BC, the British forcibly brought other Tamils to Sri Lanka to work tea plantations in indentured servitude, starting roughly 200 years ago. Following independence, the new Sri Lankan state denied many Tamils’ political rights, excluding them from the Sri Lankan Parliament, and they continued to experience generational poverty.

Conflict escalated to regular attacks and battles between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a militant independence movement aiming to create a separate Tamil state, and the Buddhist Sinhalese people, who are the major ethnic group in the country. In 2009, the Buddhist Sinhalese people defeated the LTTE. Throughout the 26 years of conflict, a total of approximately 80,000 deaths occurred, 350,000 people were displaced, and one million people became refugees.

All three panellists expressed that being Tamil is deeply intertwined with their lineage. Savuntharanathan, a UTM graduate student, explained that their shared history of trauma enables them to build a community together.

Chandrasegar, a fourth-year UTSC student, added, “What it means to be Tamil is holding that whole lineage, holding all of that ancestral pain, and hopefully educating the rest of the world about what it means [to be Tamil].”

Uthayakumaran, a recruitment and admissions officer at Rotman’s School of Management, recounted her difficulty in resonating with her Tamil identity at many points in her life. “Did it mean that I spoke the language, I can cook the food, I take part in the fine arts?” she asked. “Is that what being Tamil means?”

It wasn’t until she entered her graduate program that she began to further explore her identity and history. Now, she describes being Tamil not only as “very internal” and “very personal,” but also as “being resilient.”

Challenges

Being a Tamil student at the U of T also comes with its challenges. All of the speakers emphasized “miscommunication and misinformation” from others as one of the biggest barriers they’ve faced.

“Especially when I’m talking in different spaces,” Chandrasegar said. “People don’t necessarily understand, especially those who aren’t educated about the subject [of Tamil culture].” She encouraged students to further educate themselves on Tamil history by taking the time to find new resources or even asking more questions to avoid making comments that may downgrade a person’s lived experiences.

Savuntharanathan added that people tend to assume she’s from a specific place of origin. She explained that Tamil is a language and Tamil people come from around the world, not just one place.

As a child, Savuntharanathan would often struggle with the stereotype of Tamil people having “ties to terrorism,” as well. She shared, “To this day, sometimes I feel like I’m a threat to society and I don’t know why.”

For Savuntharanathan, a lot of the miscommunication she faced came from the news and political discourses. She added, “It’s so important to understand the history that we come from, to truly understand us as a person.”

Uthayakumaran noted that when she was a student in her undergraduate and graduate programs, she “didn’t know where to go to find other students” that were like her or that would understand her.

For all the panellists, being able to share their culture and personal life experiences with others enhanced their time at U of T. Chandrasegar recounted that there was a lack of Tamil representation during her first few years at UTSC. This resulted in her founding the Tamil Student Union, which provided her with a new community and safe space.

Concluding sentiments

Before concluding the event, the panellists offered advice for U of T students and the university administration as a whole.

Uthayakumaran encouraged more diversity on campus. She emphasized the importance of bringing in diverse course materials that are not “fully Eurocentric” to provide different perspectives in the classroom.

“One thing I would even tell my younger self is to not think that you’re not Tamil enough,” Savuntharanathan said. Regardless of birthplace, she explained, “We all just bring such a uniqueness, just from our own lived experiences.”

All three speakers expressed that finding a community to interact with can make university a much more positive experience. “There is definitely one community you belong in. Look for that community — and if you can’t find it, make that community,” said Uthayakumaran. “Community starts with you.”

This event was part of the university’s Our Stories series, wherein students and staff from different communities are invited to share their personal stories in commemoration of various awareness months celebrated across each campus.