A Reggae bassline is a rapturous experience. The sound waves are thorough. For many Jamaicans, there is no other way to start the day other than listening to Reggae. As the sound of our mornings, Reggae transports our minds and bodies from restful inertia to an active state. Unapologetic lyrics and melodies interlock to drive a powerful groove that strengthens the spine for the day’s work.

Reggae is an interrogative soundscape popularized by Jamaican musicians in the latter half of the twentieth century. This music, sometimes tender and often piercing, has cut a sharp profile for its resistance to many Western ideals and opposition to inequitable practices and oppressive structures.

If there ever was one, the fundamental promise of Reggae is perhaps a movement toward a common better; to remain true to the abundant and natural beauties of our world and to protest any threat to it; and to protect, console, redeem, and encourage. Thus, indignation, perseverance, peace, and love are common themes. This can be seen in Beres Hammond’s “Putting Up Resistance,” Sizzla Kolanji’s “Holding Firm,” Jah9’s “Tension,” and Damian Marley’s “The Struggle Discontinues.” Reggae’s onward march is a pulse, stirring generation after generation.

Music as relationship

Music connects us with people, places, and times. In an early morning conversation between us, we began reflecting on the best way to start the day, quickly deciding to collaborate on a morning-time Spotify playlist.

It was exciting to hope that wherever we were in the world, rhythms could connect us: the land, our people, ambitions, purpose, and histories we dare not forget.

I added Bob Marley’s mesmeric “Redemption Song,” which asks us to remember where we are coming from; the histories that brought us to this place; and, more pressingly, the ongoing struggle to forge liberating futures. We grew up listening to these songs on the radio, as cassettes in our parents’ cars, and later, as CDs in our households.

After adding the song from my Canadian Spotify account, Alphy pointed out that the music, and many others, were not playable on their Jamaican Spotify account. Marley’s songs were not available on Jamaica’s Spotify.

At that moment, we had to rethink how we could meaningfully sustain this collaboration. More broadly, we began to reflect on the importance of collectively cultivating relationships with each other — our past, present, and future — and with Marley’s music, with words, imagery, and messages centering our experiences and guiding our shared history.

– Justin Rhoden

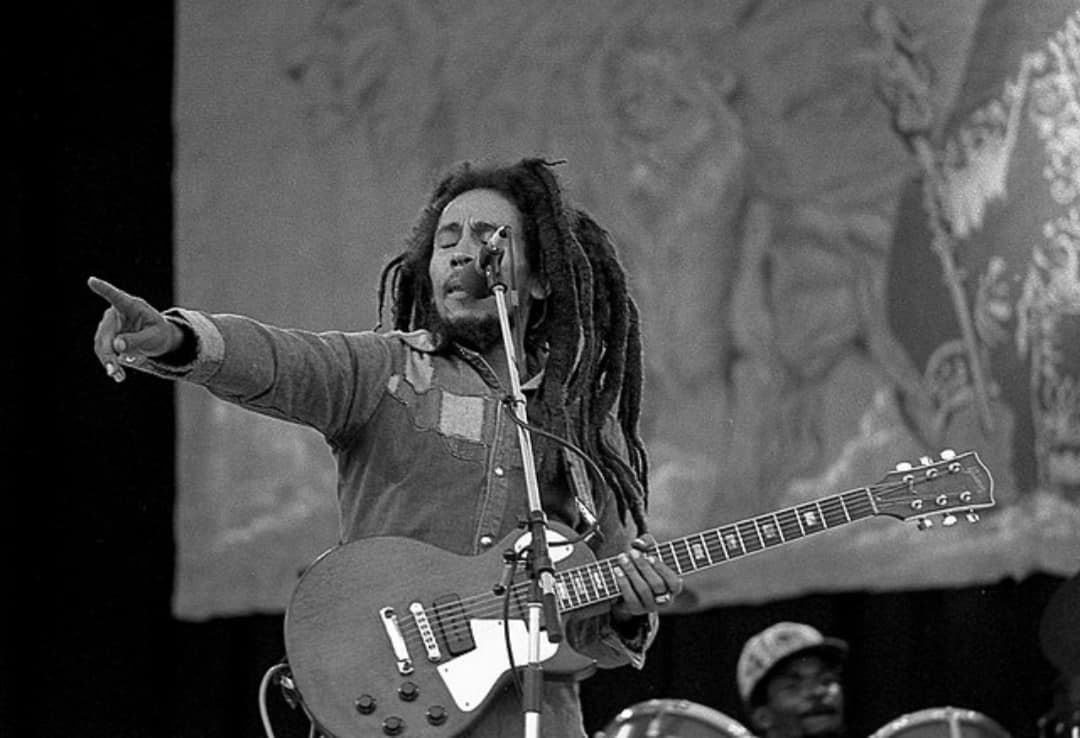

Bob Marley

Born Robert Nesta Marley in 1945, Marley is most famously known as a Jamaican singer, songwriter, musician, and early pioneer of Reggae. His name is synonymous with global hits such as “One Love,” which captures the central messages of his catalogue: peace, love, and collective work toward liberating futures.

Like many other Jamaicans who curated stories of the past and visions of the future to sustain our souls, Marley left this world, but he never died. His music is an extension of himself. In form and perception, it is a dialectic; it is a conversation between the instruments, the vibrations they produce, the melodies, the lyrics, the lands of Jamaica, its history, Marley’s soul, and our embodied beings.

Indeed, in experiencing his music, we are all present at that moment; we are all listening, talking, reflecting, thinking, singing, dreaming, and being. In engaging with his music, we all exist simultaneously at a point where time and place converge, and the perceptual labour untether us from seemingly tethered realities. With this relationship, the musical experience is complete. Without this relationship, we would let Marley die.

In the opening of “Redemption Song,” the strung chords immediately take me to my childhood home in Spanish Town, Jamaica. Engulfed in a feeling of serenity, the calmness of strong winds ruffling the leaves of tall mango trees in the yard, fruit hitting the zinc roofs, dogs barking in the distance, and the presence of mind to be in that moment.

While in that place of sincere bliss, he begins: “Old Pirates, yes, they rob I / sold I to the merchant ships / minutes after they took I / from the bottomless pit.” And in doing so, he takes me to another place. One that I do not know, but it is familiar in ways that I still cannot explain. Here I feel the violence of slave ships moving across the Atlantic and remember the peoples whose dispossession and resistance forge the freedoms I now experience and the ones I imagine for the future.

As I am taken from a place I am most at peace to a place of profound violence and struggle, I become righteously enraged. But the conversation continues: “But my hand was made strong / by the hand of the almighty / we forward in this generation / triumphantly.” Marley reminds me that despite all the violence and struggle, our connections to each other, our land, and our history persist. His music is able to locate my rage for the history of struggle and liberation and guide it to purpose.

Because of our intimate and persistent relationship, he always knows what to say to us. As one of our elders, he has the profound wisdom to say the right thing at the right time. So, it is not coincidental that “Redemption Song” was the final song on his last album with The Wailers, Uprising, released in 1980, a year before he moved on in 1981.

It is not coincidental that this song serves as the generative theme for this article. It was “Redemption Song” in its promise of the morning that reminded us once again of the oppressive structures that permeate the intimate spaces of our lives. When this structure materialized, Marley asked us again, “How long shall they kill our prophets / while we stand aside and look? Some say it’s just a part of it / we got to fulfill the book?”

How long will we normalize these assaults on our connection to self, history, people, and land?

– Justin Rhoden

Music and neoliberalism

Our relationship with Marley has shifted alongside broader patterns of neoliberal production and consumption of music over the years.

We remember growing up in Jamaica, where music announces itself loudly and beckons to all at once — from passing cars, distant parties, neighbouring homes, and handheld speakers. In our younger years, burned CDs laid on tarpaulins in town squares would quickly find their way to stereo systems and car radios, route taxis, and coaster buses dancing through the day. At school, a small gathering of friends with their ears to a phone, bopping, was a common sight. Excited leaps and screams would follow, responding to witty lyrics and flows before everyone lined up to receive the song by Bluetooth.

The recent shift to digital music streaming services is a significant recoordination of how people access and relate to music globally. Streaming is produced and policed through the contemporary legal models of ownership: private and intellectual property, music rights, and agreements with music labels like the Universal Music Group, the Dutch-American multinational music corporation with the rights to “Redemption Song.”

Notably, the dominance of digital music streaming within this broader neoliberal context is also synonymous with music production shifts. Most cited are songs created to capture listeners’ attention for at least 30 seconds to satisfy Spotify’s compensation scheme. Within all this, the discourse of what music is and what listening to it entails is redefined and promoted with no consideration for the relationships that some music sets out to build and the place, the history, and the context that grounds it.

The messages in many Reggae songs explicitly resist or are intended to disrupt the dominant neoliberal landscape in which they were produced. This tension, while productive, is too quickly resolved by neoliberal common-sense narratives of individualism that erase the range of relationships that constitute music, limit the music to the artist, and restrict their influence over the music, a problem which intensifies beyond an artist’s lifetime.

Our early morning experience forced us to confront these structural barriers constructed within the music thoughtfully. We have no choice but to earnestly contend with the ideological, material, and spiritual barriers these systems activate and the manufacturing of a pool of haves and have nots, a subversion of principles espoused by Marley himself.

An open invitation

In the neoliberal narrative of individualism, the importance of music as a relationship is subverted and erased and so is the importance of protecting and sustaining these relationships. We must understand what Reggae embodies and its significance for individual and collective selves, lands, peoples, and their histories. This understanding requires meaningfully engaging with the structural conditions that disrupt our ambitions to collaborate and build relationships. We are never beyond redemption.

In the spirit of Reggae, we invite you to collaborate on our early morning Spotify playlist and build relationships that complete the music by listening, reflecting, feeling, talking, learning, asking questions, being, and then collaborating, organizing and resisting, By joining, you are responsible for conversing with each element of the music; let it speak to and move you.

What if some songs are unavailable, or you cannot access Spotify? In that case, we hope you are equally outraged at the neoliberal logic that prevents us from connecting even with technologies that can connect us. More importantly, we hope this rage will move you to defend a future that would nurture the kinds of relationships we imagine here and do so unapologetically. After all:

“Won’t you help to sing?

These songs of freedom,

‘Cause all I ever have,

Redemption Songs”