Content warning: this article contains a brief mention of suicide.

More and more Canadians need doctors, and this is a profession that more and more Canadians are blocked from becoming.

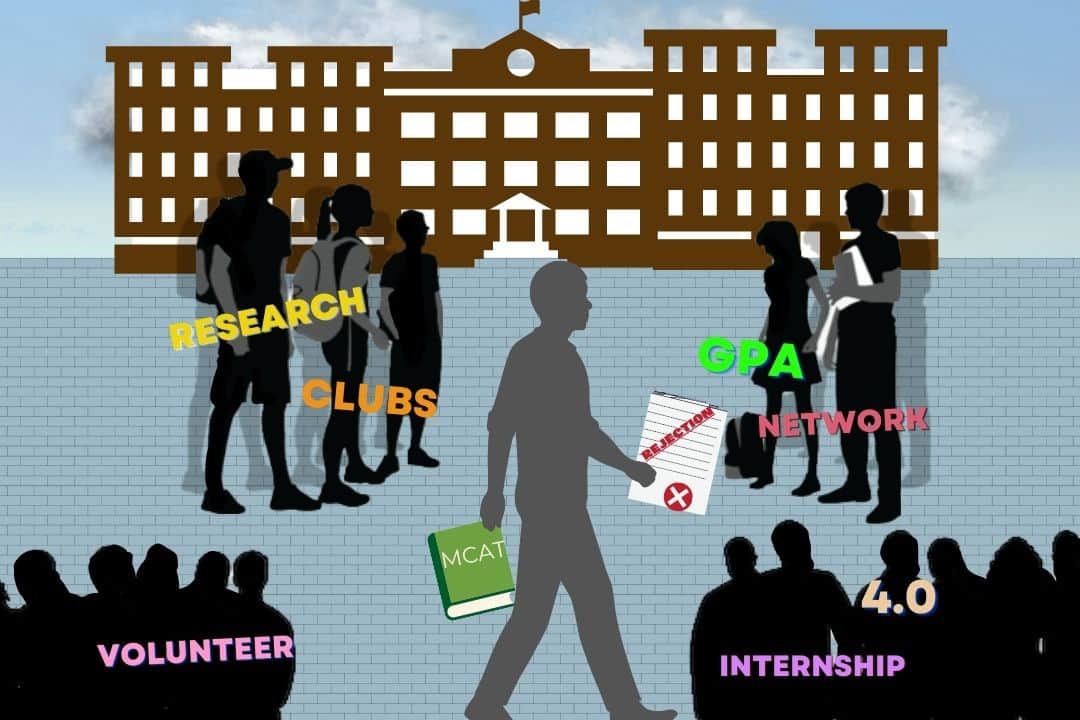

Medical schools turn away 80 per cent of annual applicants, while a Royal Bank of Canada study warns of a shortage of 44,000 physicians by 2028. Besides the ramifications for patients themselves, the challenges for physician hopefuls include stress-filled years spent at university, a lack of other options, and even suicide.

Who is keeping students out of medical schools?

Provinces control both the number of spots in medical schools and the number of positions for residency — a multi-year mandatory training program in hospitals that is required after medical school to become a fully licensed physician. Provinces are hesitant to increase the number of medical school spots when there is not a similar increase in residency spots to take them in afterward.

This can lead to undergraduates struggling for years while trying to position themselves best for acceptance. A go-to place to vent about these issues, the subreddit r/premedcanada, has seen its subscriber count grow from virtually none to 22,600 over the past five years. Its top keyword and most mentioned university is “U of T,” which is possibly the undergraduate university most notorious for physician hopefuls.

Anita Acai, an assistant professor and education scientist at McMaster University who almost exclusively teaches undergraduate students aiming for medical school, told The Varsity about how “people start to equate their identities with their career” and those who don’t get into medical school feel like personal failures.

A shortage of spots in Canadian medical schools leads some students to look abroad. Charles Pinto, a third-year life sciences student at U of T said in an interview with The Varsity, “You’ve got relatively better chances trying to go to the States, even as a Canadian, then as a Canadian trying to apply to Canadian schools.”

What limits residency spots?

Even after the hurdle of being accepted into medical schools, students face the second challenge of scoring an increasingly competitive residency spot.

A 2017 study from the Canadian Medical Association Journal found that the average number of residency positions students had to apply to was 18 to 19, with candidates having to travel or do an excessive amount of extracurricular activities to be competitive.

Medical school graduates are matched to residency positions by an external organization called the Canadian Residency Matching Service (CaRMS). In 2022, it matched 93.7 per cent of those graduating from Canadian medical schools and 81.2 per cent of those educated abroad, in the first round, on top of a small number of remainders in the second.

However, besides the numbers that are admitted, some people do not get residency positions, even after having completed roughly eight years of schooling at this point. Last year, 35 Canadian medical school graduates and seven foreign-educated graduates did not get positions after the second round. Forty eight Canadian medical graduates who were not matched in the first round did not reapply in the second.

Positions that don’t usually get filled

Many residency positions go unfilled, including family medicine posts, posts that require French speaking skills, and positions in rural areas.

After the second round of residency offers of 2022, there were still 115 unfilled positions, of which 99 were in family medicine. Seventy three of these unfilled family medicine positions were in Québec, 15 in Ontario, and 11 in Western Canada.

Some medical students take this as a motivator to go for these unwanted positions.

Benjamin, a student who asked to only be identified by his first name out of fear of repercussion from medical school review boards, said in an interview with The Varsity, “With the current crisis in family medicine, many minority patients cannot even access walk-in clinics, as English is often the primary language at those places.”

Specialty

Michael Carter, a professor of industrial engineering at U of T, told The Varsity that provincial governments determine how much doctors are paid — which, in turn, determines which specialties people vie for. “15 years ago, they changed the rate that they were paying family docs and started paying them more. Still, in my opinion, not enough to try to convince people to move from specialties,” he told The Varsity.

For students who want to go into the more competitive specialties, competition is fierce.

Danika Snelgrove, a first-year student at Memorial University’s Medical School, told The Varsity that her colleagues “who want to be in competitive specialties typically eat, breathe, sleep, those competitive specialties.”

“There’s this idea of, if I’m going to put myself through eight years of school, and then an additional five, at the very least, years of residency [and] of sleepless nights, [I would] want to come out being like the coolest possible thing,” said Pinto.

“No one really wants to go into family medicine unless it’s something like ‘my parents are family doctors,’ ” he said, adding that he himself is interested in that field.

Unfairness

This system, which has so many checkpoints for meritocracy, can lead to unequal results.

According to CaRMs 2022 data, out of the 529 graduates from Canadian medical schools, 141 came from households that earned more than $150,000 per year. Thirty nine graduates had declined to take part in this survey.

Out of those who graduated from foreign medical schools, 26 came from households that earned more than $150,000, and 286 came from households that earned less, including 125 from households that earned less than $25,000.

Benjamin also told The Varsity, “I worked three concurrent jobs while as an undergraduate student, and this had a major effect on my mental health. I was constantly burnt out and was extremely isolated.” The resulting GPA of 3.8 and lack of extracurriculars put him at a disadvantage, though, in the end, he still got two positive responses.

Carter expanded on a lack of central planning that has led to the current system. “One of the problems we have with Canadian healthcare is that the federal government gives money to the province, but they can’t tell the province what to do with it. The province gives money to the hospitals, but they can’t tell them what to do with it. The province gives money to the doctors, but they can’t tell them what to do with it,” he explained.

“It’s difficult if there’s nobody in charge.”