Content warning: This article discusses disordered eating and diet behaviour.

In season four episode two of Sex and the City, the main character Carrie Bradshaw reflects on her more financially constrained past self by loftily stating that, “Sometimes, I would buy Vogue instead of dinner. I just felt it fed me more.”

Albeit fictitious, when an influential character like Bradshaw says this while exhibiting a perfectly toned body and living a glittering New York City lifestyle, the show’s target audience of young women cannot help but sense the undertone of her line: a woman’s key to a successful love life and physique is skipping meals and forcing a sense of nourishment from high fashion magazines with thin models.

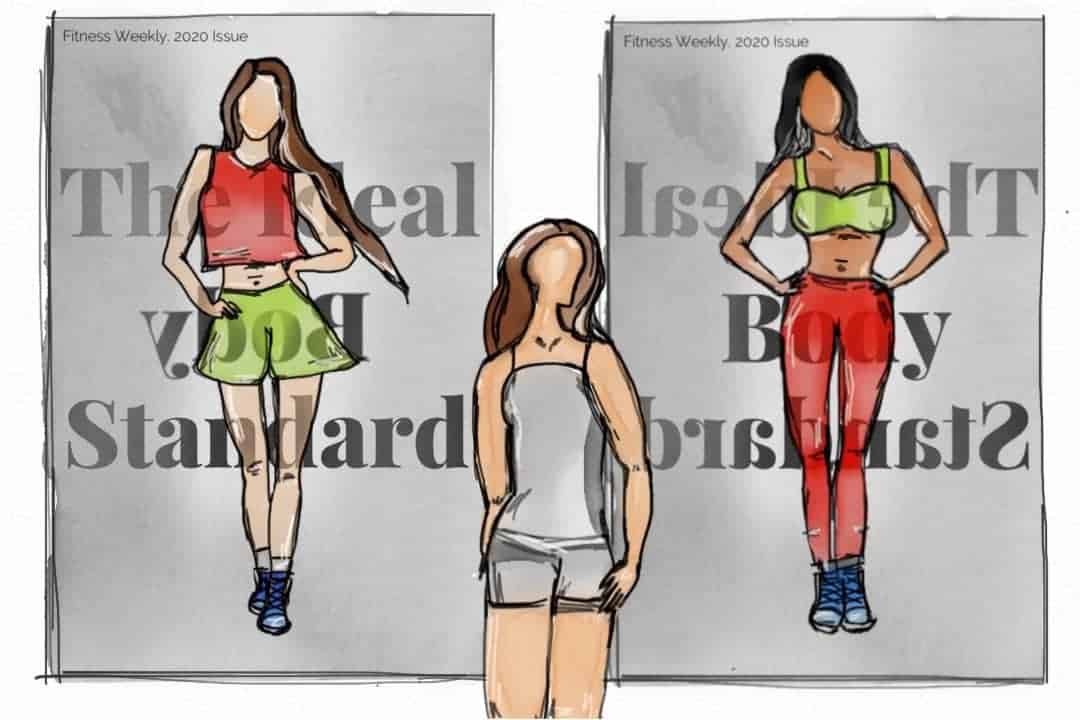

Given that this Sex and the City episode aired in 2001, Bradshaw’s source of fulfillment — or desire to keep up with beauty standards — could only have have come from physical copies of magazines or runways or television. In 2023, however, we are overflooded with beauty-standards-turned-guidelines that dominate Instagram feeds and TikTok “For You” pages (FYP). It is untrue that these standards did not exist before, but it is also undeniable that they have more deeply infiltrated our everyday lives than 22 years ago in the pre-social media age. This is a big problem.

Exactly what is happening on social media?

One of the main sources of entertainment from social media comes from the ability to follow celebrities’ accounts and feel as though we have our foot in the door that seemingly leads to their private lives. What this “following” also does, however, is distort our conception of just how detached from ‘normal’ lives these celebrities are and how unattainable it is to have the figure that Bella Hadid or Emily Ratajkowksi — both on the rank of most followed models on Instagram — work to have.

In the Sex and the City episode I mentioned above, Bradshaw’s fascination with models stems not only from the glitz and glamour of the world of fashion, but from the understanding that the models live in a different world from her. She makes the distinction clear when she hesitates to be part of a fashion show because she does not want people to think that she cannot tell the difference between a model and herself.

In this generation, however, users of social media platforms are prone to casually scrolling through their feeds to find a beautiful, but meticulously planned and edited, photo of one of the highest paid models in the world right before seeing a photo of your school friend. While we may not be determined to compare a post from our friend — who is not paid to pose — to that by a runway model, social media seemingly breaks down the barriers and contributes to our conflation of our social media identities to that of celebrities. A side of us may reassure ourselves that celebrities’ beauty standards are unreasonable, but celebrities are simply so deeply entrenched in the platforms of our main source of communication that it is difficult to ignore and easier to compare and idealize.

Kaisa Kasekamp, a second-year student at Trinity College who is most active on Instagram, has seen the platform’s domineering power. It strips away the factors that build one’s ordinary life to simply compare picture to picture and post to post; we see Bella Hadid’s sculpted figure in a bikini right after scrolling past a colleague’s picture from the beach — just as if the model is one of our friends to reasonably compare ourselves to. This subtle function of social media is potent enough to set internalized beauty standards but, as Kasekamp puts it, “We just don’t know how to deal with these expectations.”

The models are further and dangers are closer than you think

Kasekamp and I, both in our early twenties, can attest to the twinge of frustration we feel upon seeing a celebrity’s “perfect” body and face on Instagram against our wills when we are wound up with midterms, late night fast-food, and no sleep. The false proximity we sense to celebrities on a daily basis intensifies standards held on ourselves. We can, thus, only imagine how overwhelming it can be to be a teenager during these times amidst social media’s beauty standards that have reached saturation point.

TikTok — where the largest user demographic is youth between ages 10 to 19 — does not officially allow for explicit promotion of eating disorders, but there are plenty of loopholes. Research has proven that a mere day of liking and sharing certain content can dramatically transform one’s FYP and engaging with content with #WhatIEatInADay can quickly lead to videos of restrictive diet content with hashtags #detox and #modeldiet gradually.

Upon downloading TikTok, I tried searching up the aforementioned popular hashtag and landed on a video, for which a recommended search that popped up was “fast metabolism.” To my horror, I found hundreds of comments below that read: “I would do anything for a fast metabolism, I’m so sick of surviving off of shakes” or “I just want to be skinny effortlessly man.” The most jarring comments are on the line of, “This actually looks kind of healthy.”

The video did have a combination of good food, but the thumbnail photo of it was the user in workout gear flaunting their body, which the users in the comments seemingly adored. Whether the user intended it or not, their video — through a supposedly harmless hashtag like #WhatIEatInADay — targeted hundreds of young users desiring to be skinnier with a fast metabolism to eat what “actually looks kind of healthy.”

There is an incredibly high number of TikTok users at a vulnerable and impressionable age and an uncontrollable amount of content that promotes a certain body and set of eating habits. To manage this, TikTok has been working with the National Eating Disorders Association in America to guide users to educational resources, but the recent Congress hearings of TikTok’s CEO Shou Zi Chew serve as a testament to where the root problem is.

When the lawmakers questioned Chew on TikTok’s promotion of disordered eating, illegal drug sales, and sexual exploitation, the CEO responded that the concern is not unique to their app and that “we don’t think it represents the majority of the users’ experience on TikTok.”

But it does! There are millionaires like Chew with enormous power who knowingly turn a blind eye toward the effect the platforms have on youth, and there are millennials and older generations who don’t understand why teenagers cannot simply get off their phones. The previous generations’ dismissive, patronizing, and uninformed conception toward social media is allowing for the ongoing proliferation of harmful content that is internalized by young users.

When we use Instagram to communicate with friends, we also see the “inspirational” bodies of celebrities mixed within our friends’ posts. The comparisons made are subconscious and we search for what they eat in a day on TikTok or YouTube, which leads us to recommended videos on restrictive diets and disordered eating. We are confused and overwhelmed too.

Content moderation is helpful for a younger audience, but I do not see repeated bans and censorship of certain posts or videos as the optimal answer. Social media is still quite a recent emergence and progress will be incremental, but I believe the first step is removing the barrier between the generations with power and youth: take our lives — and whatever comes with it — seriously.

Eleanor Park is a second-year student at Trinity College studying English and religion. She is The Varsity’s associate comment editor.