Content warning: This article contains descriptions of artwork that depicts violence against women.

The Artist Project is an art exhibit held annually at Toronto’s Better Living Centre, where independent artists can show their work. This year, the exhibit was held from April 13–16. I was lucky enough to attend and even luckier to have interviewed artists Danielle Cole and Martin Murphy.

Danielle Cole

Danielle Cole is a Toronto-based artist who specializes in collage work. Her meticulously selected images from vintage magazines are assembled into layered webs of narratives concerning gender, culture, and society. Cole’s commissioned art can be found on a billboard in Greenwich Village, and this was her fourth time exhibiting at the Artist Project.

Cole’s deliberate, tantalizing assemblages are a fascinating approach to exposing the absurdity of gender roles. However, she was not always certain that collage was the right medium for her. She explained: “I didn’t feel I had permission to be a collage artist exclusively… It is seen as ‘craft’, and as a feminist, I felt like it is quite a belittled artform.” Throughout much of art history, art forms we consider ‘crafts’, such as fabric handiwork or collage, were relegated to the category of ‘women’s work’ and not seen as ‘high art’ by the male-dominated art world.

Cole changed her mind at an exhibit by Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu, whose collages concern race and gender. “Once I saw her work,” said Cole, “it gave me permission to follow my own path and just work in collage,”

Cole’s use of vintage materials allow her to use humour to attract her audience into considering the serious social issues her work depicts. “I’ve always aspired to have a humorous voice to invite the viewer to not be offended,” said Cole. “I don’t want to point an accusatory finger; I want to put forward an invitation to say, ‘Let’s look at this laughingly and let’s start picking it apart.’ ”

The humour lies in the absurdism of Cole’s pieces. Often, the women appear mischievous and knowing, which Cole confirms is part of how she uses satire to mock the expectations imposed on women. She originally selects images of women from vintage magazines, where they stand happily in front of dishwashers or do chores, then subverts them: “When I take their glowing beautiful joyous faces and put them in a strange situation… [they are] not then promoting this propaganda of domesticity. [They are] mocking it.”

Cole is sometimes faced with the difficult task of manipulating the redundant portrayals of women offered by vintage material to create darker pieces. She succeeds with pieces like “Always Witches to Be Found”, which depicts four immobile women stacked upon each other. One has cleaning tools impaled in her spine; another wears a pained expression, her arm in a man’s tight grasp. The piece is a tribute to the women in fifteenth-century Scotland, whose sexual appeal or failure to comply with gender roles prompted morbid accusations of witchcraft.

This piece appears in Cole’s collection “Sirens and cowboys,” which criticizes gender ideals. While sirens represent the mythologized embodiment of the beauty and seduction attributed to the feminine ideal, the cowboys are her interpretation of the masculine ideal: “Cowboys I also view as mythological creatures. They are meant to be stoic and heroic, and are very two-dimensional… So they are stuck in their own [gender] identities, and I think they are a counterpoint to these [feminine] mythological creatures.”

When experiencing a creative block, Cole’s advice on finding a source of inspiration emphasized the importance of resisting idleness: “When you create a discipline around artmaking, you don’t act like you have to wait for inspiration.” She explained that this waiting game often excuses artistic inaction, which only hinders growth and confidence. Cole stressed that creative growth is very important to finding inspiration, and she recommends looking “beyond your practice” and allowing yourself to be artistically vulnerable.

Martin Murphy

Martin Murphy is a visual and performance artist. He grew up in Unionville and attended art school in Toronto until he left to pursue a career in performance. Later, he worked with visual effects for franchise films like Jurassic Park, Star Wars, Avengers, and more. He is currently a full-time painter in Vancouver. This was his first year with the Artist Project.

Art has always been a part of Murphy’s identity. At 10 years old, he asked his parents for a sewing machine to make puppets. He explained, “My parents didn’t give me toys for Christmas. They gave me things to make toys.” When he was 15, he joined the local community theatre.

Murphy’s oil paintings often detail people and koi fish, yet his precision allows even still lives to emulate a sense of intimacy, as though the viewer breathes in unison with his clocks and teapots. His koi show great detail, from their glistening heads to bubbles in the water. He carefully captures the individuality of his portraits’ subjects, where each appears distinctly themself. “Even when I paint the fish, I try to be… ‘faithful’ to their expression, skin quality, how the light reflects upon the shininess of the lips, and around the eyes… little things like that,” he said.

Murphy’s experience working in the digital world with visual effects enhanced his talent for detail. Describing the visual effects process as both “technical and complicated,” he elaborated on the challenges he faced on the job, such as mimicking “the refraction in an eye, how light goes through skin… and the quality of hair.” He also explained how taxing a “corporate, deadline-oriented” job in the film industry can be: “It pays very well. But it’s very long hours, and it’s quite punishing physically because you’re just there at your desk for sometimes 18 hours a day.” While he’s appreciative of his experience, he is glad to be creatively fulfilled as an independent artist.

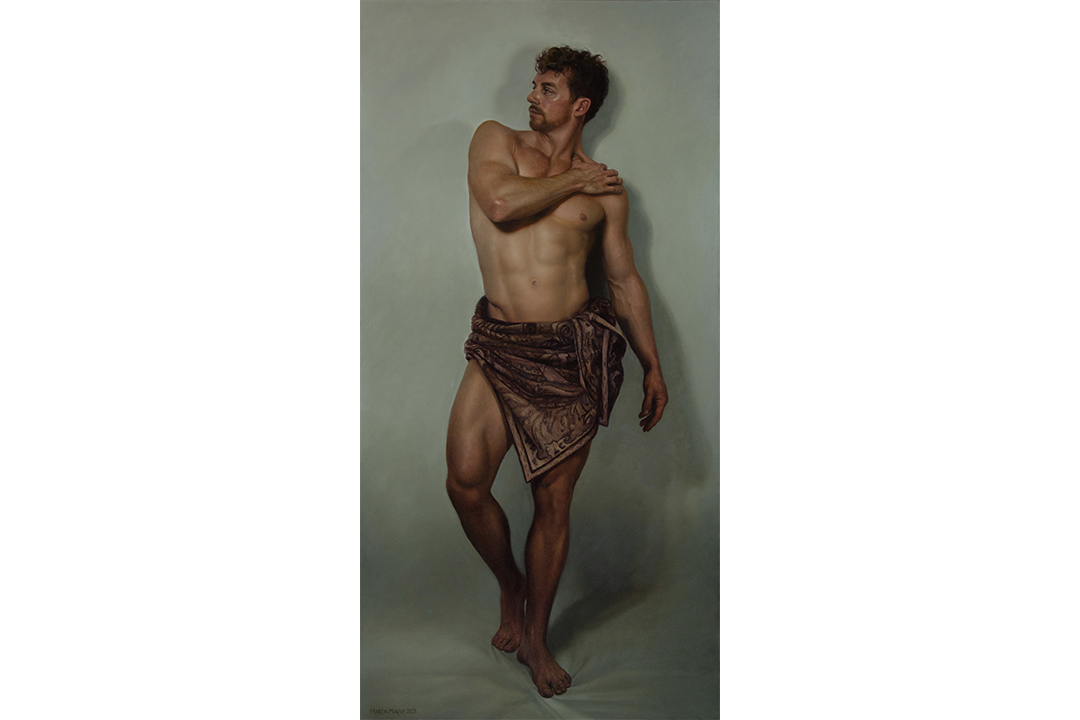

Murphy also has a background in theatre and dance, which he says further contributed to his thoroughness: “Dancing gave me a wonderful sense of anatomy, drama, and how the body works,” His piece “The Landscaper” depicts a male dancer’s figure, nude but for a towel around his waist. Murphy’s anatomical precision defines the subject’s muscled core, pelvis, calves; his understanding of movement captures the careless shrugging of one shoulder, the bending of a knee, and his attention to drama casts shadows behind and around the subject contouring his face with sweat.

Regarding the difficult search for inspiration amid creative stagnation, Murphy referred to the words that he attributes to writer and art critic Jerry Saltz: “Inspiration comes from work.” He described the importance of stubbornness to chip away at creative paralysis. “When you’re stuck, you just… need to just pound away on that painting that isn’t working. And then after an hour you’re like, ‘Holy crap, this is actually working,’ and boom! You’re inspired and you’re back on the track again, and the train is going.”