A 2022 study by Dr. Tamorah Lewis, the division head of pediatric clinical pharmacology at the U of T-affiliated Hospital for Sick Children, suggests that social factors like maternal race may affect outcomes for infants born with complications.

The study looked at children born with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD) and found that while factors like premature delivery, inflammation of the lungs before birth due to placenta infections, and long-term use of mechanical ventilation could affect outcomes, maternal race should also be considered a factor. The results of this study suggest an association between hospitalized premature infants with severe BPD born to Black mothers, differing hospital treatment, and worse late outcomes. These infants had an increased likelihood of death and increased length of hospital stay compared to preterm infants born to white mothers.

What is Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia?

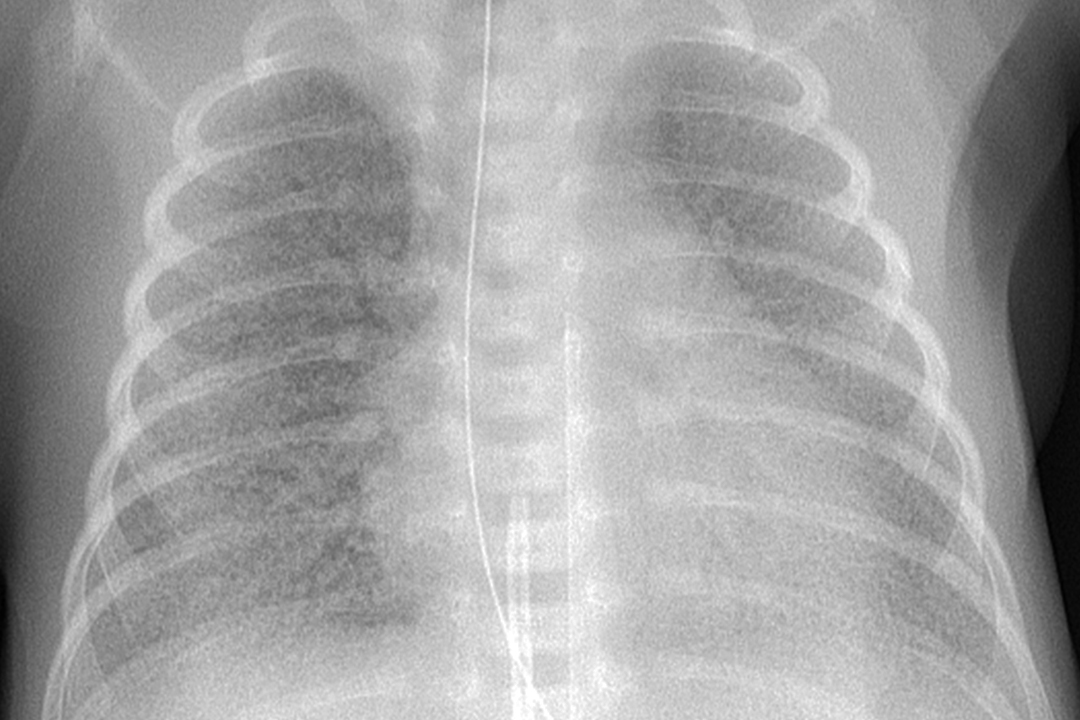

Infants that are born prematurely are often at risk of a number of complications after birth. A prevalent issue in premature birth is BPD, a chronic lung disease. Both pre- and post-natal factors can result in the underdevelopment of the lower respiratory tract, which might result in BPD.

Symptoms of BPD include laboured and rapid breathing in newborns and a bluish tint near the mouth area. This disease can be exacerbated by excessive use of mechanical ventilation. Premature births usually require oxygen therapy because newborns tend to have weaker lungs. The inability of the lungs to support proper breathing, coupled with underdeveloped blood vessels near the alveoli — the site of gaseous exchange in lungs — results in inefficient gas exchange and breathing problems.

In the United States, BPD affects 50 per cent of infants born after less than 30 weeks of gestation. According to the Canadian Neonatal Network, 28.1 per cent of infants born after less than 25 weeks are diagnosed with BPD.

How the study worked

The study harnessed an extensive record of patient data from various hospitals and medical institutions in the US with severe BPD dating from 2015 to 2021. The team examined records of infants born at less than 32 weeks of pregnancy and diagnosed with BPD, paying attention to records of the race of these infants’ mothers. The authors excluded children whose maternal race could not be identified, for a total sample size of 834 infants across hospitals in the United States.

The researchers recorded the number of deaths within this group of children and the lengths of their hospital stays. Then, they compared the treatment and survival of infants born to Black and white mothers. The differences between the two groups were determined using statistical analysis — specifically, the Mann-Whitney U test, a statistical test used to compare two groups. In this study, this test was used to garner whether there is a discernible difference in outcomes of BPD in infants born to Black mothers compared to white mothers.

As is often the case with clinical research, sample size may be a limitation for this study. The sample pool is limited to the BPD Collaborative centers available for study. As such, the study is not fully representative of the entire population of the US, so we must be cautious when extrapolating these findings to the general population.

Defining maternal race was another limitation of Dr. Lewis’s study since there currently isn’t a widely accepted standard for defining race. Therefore, the racial categories used in this study may vary from definitions in another study. The study only looked at differing outcomes between Black and white mothers. Moreover, lack of access to paternal race limited information regarding infant race.

Differences in treatment based on race

The study found that babies born to Black mothers were more likely to have lower gestational ages and lower birth weights compared to white mothers — both of which result in a greater risk for the development of BPD. When comparing Black and white patients, however, the authors emphasized their opposition to incorrect assumptions that people within a given racial category are alike, and to pre-existing misconceptions regarding inherent biological differences between racial groups. Instead of reinforcing the reductive construct that differences between Black and white infant BPD outcomes were due to biological reasons, they hoped that their results showed that what might superficially and incorrectly appear as biological difference between the races is likely instead a difference in healthcare treatment.

Typically, treatments for BPD involve some degree of breathing support such as mechanical ventilation. Treatment-wise, children born to Black mothers were more likely to receive invasive ventilation compared to children born to white mothers. Additionally, once discharged, infant survivors of BPD born to Black mothers were less likely to be given supplemental treatments like home oxygen compared to infants born to white mothers.

In other words, race itself is not a biological variable; rather, structural inequities in healthcare due to race are so systemic that race might affect biological outcomes. In the case of BPD outcomes, Black infants are at higher risk of death in the short term and less likely to receive proper care. Thus, the survival of newborns suffering from BPD seems to also be impacted by the treatment disparities between white groups and Black groups.

Implications of the study

This study sheds light on the ongoing problems of racial disparities in the healthcare system. It provides evidence that suggests a real difference in the healthcare administered to different racial groups. As such, it pushes for the needed changes to make a palatable difference in healthcare.

Time and time again, Black mothers receive blame for the health of their children and are less likely to be taken seriously by healthcare providers. Furthermore, the negative experiences faced by Black mothers may make them more reluctant to engage with healthcare institutions, as they often report negative experiences in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit — a care unit in hospitals responsible for the care of sick and preterm infants.

BPD as a diagnosis is already a burden on new parents, and it is imperative to identify and address discriminatory, unwarranted barriers to proper treatment. We need further research to gain a better understanding of the problems in healthcare that lead to social disparity in BPD treatment and medical treatments in general.

Dr. Lewis will be a keynote speaker at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine Research Showcase at the Bahen Centre on July 7. The event is open to anyone in the Faculty of Medicine, including undergraduate students, faculty, graduate students, and staff. The staff of the event has also encouraged Arts & Science undergraduates who are doing research in the faculty to attend.