Content warning: This article mentions death and discusses anti-Black racism.

On April 15, fighting between the Sudanese military and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) erupted in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. The conflict has spawned a humanitarian crisis affecting the families, mental health, and academics of Sudanese students at U of T. In response, Sudanese students and professors have fundraised for medical assistance and have called on the university to provide financial and academic support to those affected by the fighting.

In interviews with The Varsity, members of the Sudanese U of T community argued that the university’s limited response to the conflict reflects the anti-Black tendency to see conflict in majority Black countries as ‘less important’ than conflict elsewhere in the world.

Background on the conflict

In 2019, after months of pro-democracy protest, the RSF and the Sudanese military helped overthrow former president Omar Al-Bashir, who came into power through a coup in 1989. The International Criminal Court is seeking to try Al-Bashir for genocide, torture, rape and other allegations of crimes committed from 2003 to 2018 in the western Dafur region.

The military and the RSF established a joint military-civilian government, promising to turn over power to civilians. However, in 2021, General Abdel Fattah al Burhan, the leader of the Sudanese military, and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the leader of the RSF, overthrew the joint government, blocking democratic elections and establishing a military government.

In December 2022, under pressure from the international community, Burhan and Dagalo signed a preliminary deal to give power back to the civilian government. Negotiations continued until this April, when disputes about which force would have ultimate authority over Sudanese fighters and weapons sparked violence.

“I have watched my home that used to encompass many generations of my family destroyed and turned into rubble.”

So far, the fighting has displaced more than two million people and resulted in at least 959 civilian deaths. With no end in sight, the conflict has also resulted in a humanitarian crisis, leaving civilians in deteriorating conditions with limited access to food, water, and medicine.

Impacts on students

In interviews with The Varsity, Sudanese students at U of T reflected on the conflict and its impact on their families and mental health.

“I have watched my home that used to encompass many generations of my family destroyed and turned into rubble,” wrote Hiba Taha, a second-year graduate medical student, in an email to The Varsity.

Taha explains that the conflict has left many members of the Sudanese diaspora, especially students studying at U of T, struggling financially. The knowledge that their families back home lack food, water, electricity, and support places a mental burden on students, who must often attempt to balance studies with communicating to and supporting family.

During the 2023 winter semester, Taha took a leave of absence to be with her family, which delayed her degree. Such delays can result in extra fees for graduate students, according to the School of Graduate Studies.

“As an academic and educational institution, U of T should be able to provide assistance with students who were recently displaced by the war, as well as current students who have family affected by the war,” she wrote. However, other than an email from the University of Toronto Students’ Union, Taha wrote that she has yet to receive any emails from the university that provide support or acknowledge the conflict.

On April 29, Vice-President, International Joseph Wong released a statement on behalf of the university addressing the conflict. He expressed “concern and sympathy for those here and abroad affected by the current conflict in Sudan.” According to Wong, the Office of the Vice-Provost has reached out to student groups to check on their well-being and confirm their awareness of available travel, health, and academic supports.

Asking for support

Leena Badri started attending U of T in 2018 and graduated in 2022 with a double major in international relations and peace, conflict, and justice, with a minor in African studies. In a written statement sent to The Varsity, she explained that, during her four years of undergrad, she felt “mentally and emotionally overwhelmed” by the turmoil taking place in Sudan, which included a revolution, crackdowns on protesters, and a coup.

“It felt like I either had to choose between my mental health and my academic progress,” Badri said in an interview with The Varsity. “It felt like I had to sacrifice one for the other all the time.”

Badri noted that she struggled to access academic support, mental health support, and accommodations. She felt lucky to have professors who went “above and beyond” by checking in with her. However, she lamented the lack of guidelines about what situations qualify for an extension and how to ask for one. “The onus is on me, and I would sit there and draft these emails and erase them and draft them and erase them because I was like, ‘Okay, does this sound too much? Does this sound too sad?’ ” she said. “That alone was another level of stress.”

Badri argued that U of T should create guidelines or hold events so that students know what accommodations they are entitled to.

When asked about these student criticisms of the current process for requesting extensions, a spokesperson for U of T wrote that the university “encourage[s] students who need academic accommodations to contact their Faculty or college registrar’s office.”

Double standards

Badri also criticized U of T’s approach to supporting Sudanese students during times of conflict, noting differences between how U of T has responded to the Sudanese conflict and other recent conflicts. She highlighted that, in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, U of T extended “various support programs,” such as emergency aid, and accepted displaced students through its Scholars at Risk program. The Scholars at Risk program offers financial aid to a select number of current students who have sought asylum or have been a refugee in the past five years, or whose schooling has been impacted by changing political environments.

“There is an undeniable bias both in society and academia, that Africa = conflict, and that these things are just run of the mill.”

“I am glad that U of T undertook such efforts, as they were deeply important,” Badri wrote to The Varsity. However, she noted that no such programs exist for Sudanese students. “When you are from a country like Sudan… many people can’t even point out on a map, and when they hear [it] is in Africa, their eyes immediately gloss over,” she wrote. “There is an undeniable bias both in society and academia, that Africa = conflict, and that these things are just run of the mill.”

“When responses to such issues are individually decided by the institution without any permanent guidelines,” Badri wrote, “it sends the message that the only issues that are important are the ones that the governing body personally finds important.” When asked whether the university has any guidelines for how it responded to conflicts in students’ home countries, a U of T spokesperson said the university keeps in contact with “relevant student groups” during global events like the war in Sudan, and mentioned that students can reach out to their registrar’s office to request academic accommodations.

In an interview with The Varsity, African Studies Professor Nisrin Elamin, who is from Sudan and was in the country when violence broke out, shared similar concerns. Compared to the government’s response to the war in Ukraine, Elamin noted a lack of financial support from the university, and a lack of assistance from the federal government about expediting processes, such as work visas, for Sudanese nationals.

According to the Government of Canada’s website, the government has implemented “temporary measures for Sudanese nationals in Canada” to let them prolong their stay in Canada. In addition, the government has also provided humanitarian assistance such as funds for food and water.

“In some ways, the university’s response is mirroring the Canadian government’s response, which is also too little too late,” Elamin said. She attributed the inadequate response of both the university and Canada to anti-Black racism and double standards regarding African countries or majority Black countries.

In a statement to The Varsity, Wong wrote that he was “troubled to hear of concerns within our community about how the University is responding.” He noted the public statement issued by the university and direct outreach from university staff to community members. Wong pledged to “provide updates and further supports to our community as needed,” including by providing information about government visa and aid programs.

A spokesperson for the university also highlighted the university’s mental health supports — including MySSP and same-day mental health appointments at the university’s three health and wellness centres — and the university’s creation of the Anti-Black Racism Task Force, as well as other initiatives to support Black students and scholars at U of T.

Taking action

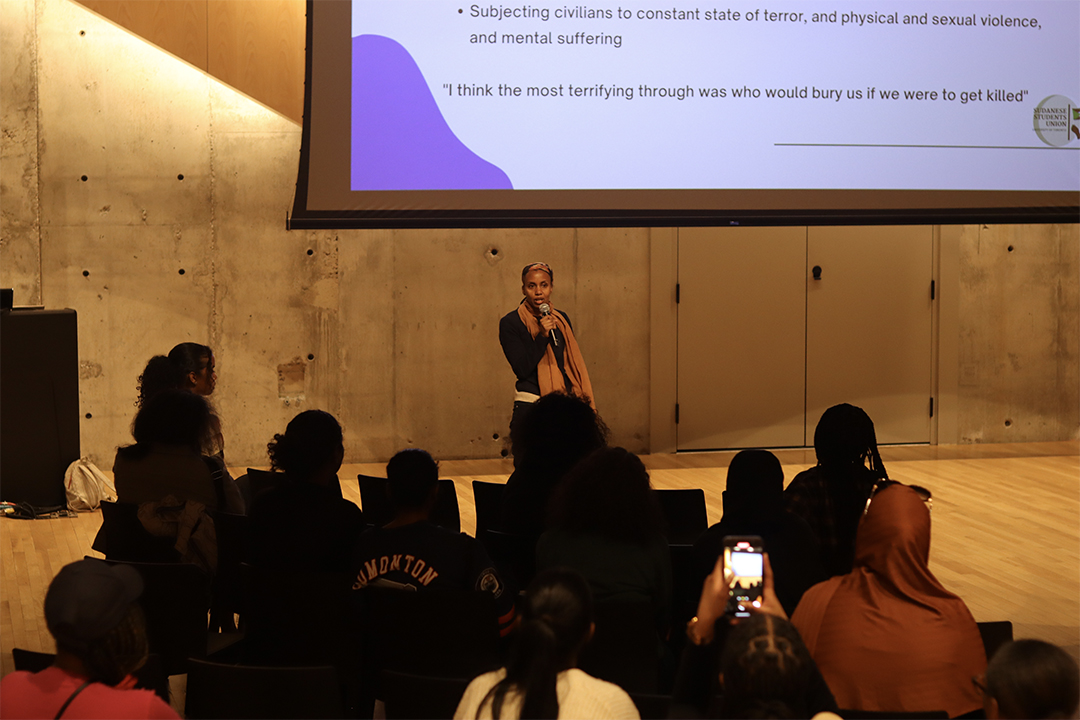

The Sudanese Student Union (SSU) held a fundraising event to raise funds for the Sudanese Doctors Union, an organization currently providing medical support in Khartoum, as well as to increase awareness of their initiatives and the ongoing conflict. As of publication, the SSU has also raised more than $9,000 for emergency medical relief through an online fundraiser.

In response to the crisis in Sudan, Elamin and several other faculty members signed an open letter to the University of Toronto requesting financial aid and further support to help Sudanese students and their families through the immigration process. In an interview with The Varsity, Elamin advocated for expanding the existing Scholars At Risk program to Sudanese undergraduate and graduate students as well as established scholars.

Elamin said she and the other faculty staff who had signed the letter met with Vice President Wong about potential future support for Sudanese community members.

With files from Jessie Schwalb.