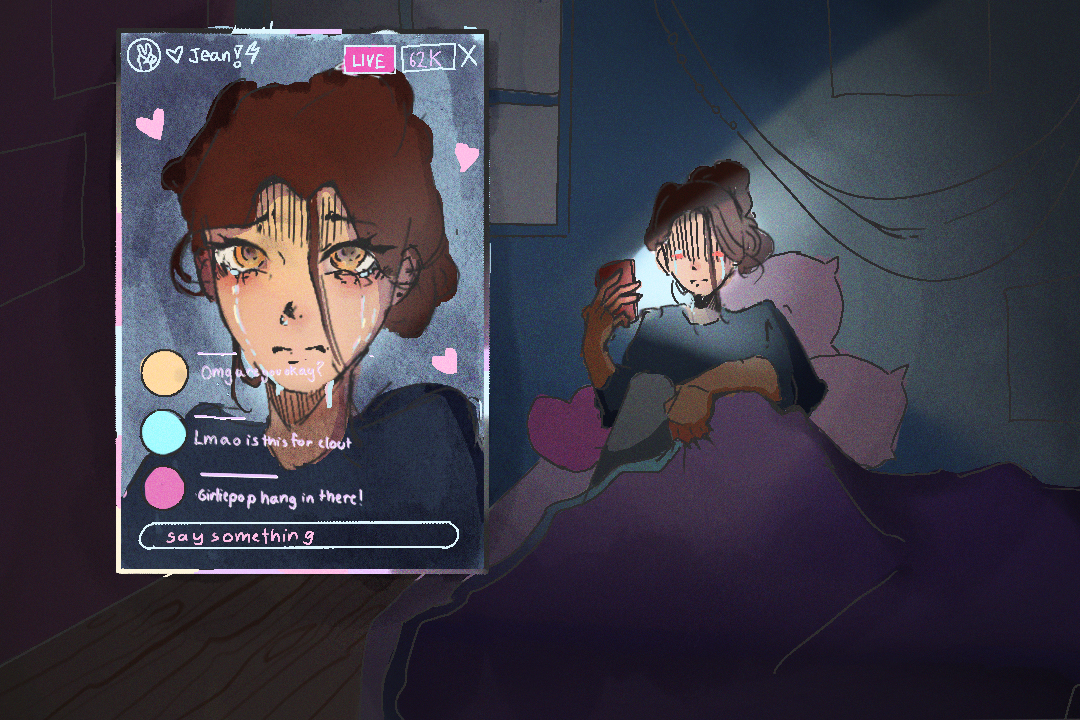

There are few things the internet loves more than a trauma dump. On TikTok alone, there are 24.3 billion videos tagged with #trauma, ranging from harrowing retellings of assault, antagonistic parental relationships, panic attacks, and depressive episodes. Some tearful, others nonchalant, there are countless creators who wear their bleeding hearts on their sleeves like a badge of honour — packaging all their pain into a quick clip for our entertainment.

Gen Z is often criticized for this ‘trauma culture’ as the commercial aspect of social media seems antithetical to the raw emotion associated with the experiences being shared. Nevertheless, while death and pain are profited off of in countless ways, this online ‘trauma culture’ is one of the few ways individuals can profit off of their own pain.

Although these behaviours are associated with Gen Z, I believe that our generation is not the first to foster a culture of pain performance, especially when we take a close look at Victorian mourning practices. When examining the practices of the past and present, we must ask whether pain performance allows us to truly heal.

Victorian mourning culture

Queen Victoria mourned the loss of her late husband until the day she died. Prince Albert fell victim to typhoid fever and passed away on December 14, 1861 at Windsor Castle with his family at his bedside. Despite rumours of a tumultuous marriage, Queen Victoria was determined to keep his spirit alive.

In fact, as Lord Clarendon noted when he visited her in 1862, she seemed to carry on as if he really were alive, “[referring] to the sayings and doings of the Prince as if he were in the next room.” His chambers were kept exactly as he left them: pen on the page, flowers in bloom in the vase, and fresh linens brought in every night. The Queen donned black garb, clung to a cast of his hand, and bedecked every royal residency with a photo of his corpse on his side of the bed.

She wasn’t alone in her tireless grief. Following Queen Victoria’s example, Victorian England saw an explosion of mourning products and practices. Handbooks such as Cassells Household Guide outlined elaborate rules for appropriate mourning periods and dress, where colours and materials had to be taken into account depending on one’s relationship to the deceased. Ceremony packages and burials were advertised in newspapers. Affluent widows and widowers pursued pageantry: opulent funeral services with a hearse and horses, velvet coverings, silk hat-bands, ostrich feathers, pages, and coachmen.

Victorian era versus TikTok

Interestingly, while Victorian England and the present day are disparate in many ways, similar factors may have contributed to the rise of their respective cultures around pain.

On the one hand, Victorian England experienced rapid urbanization that resulted in less sanitary living conditions and greater density, which produced greater risk of spreading disease. Higher death rates and closer proximity to the dead created demand for commercial cemeteries, which became more popular during the period. At the same time, industrialization meant the rising industrial class became wealthier and had the means to seek out recognition from the aristocracy, leading to a greater demand for funeral services and mourning attire that emulated that of the Royal Family and upper class.

On the other hand, social media has also created closer proximity to death and trauma, with gruesome and gut-wrenching content at our fingertips. In my experience, the oversaturation of violent media can be so desensitizing that it can be difficult to contemplate the reality of the atrocities documented on the internet and easier to regard them as fictional.

Additionally, the demand for increasingly shocking content and the opportunity to garner social capital and monetary gain via likes, comments, and views mean that individuals have something to gain by sharing traumatic personal experiences online.

In my view, these cultures are alike in that they encourage individuals to modify how they process grief or trauma to conform to a particular set of rules or limitations of a given platform. They also provide the opportunity to exploit one’s own hardship for personal advancement. However, I question if that’s the only reason people choose to participate. At a surface level, it’s tempting to assume that people consciously perform pain because they are incentivized to do so in both Victorian England and on the internet. But I also believe we engage with these cultures simply because we want to feel less alone.

Why perform pain?

Sure, there are probably some wannabe influencers oversharing troubling details from their personal life, or labelling inconveniences as trauma, or self-diagnosing mental illness in the pursuit of cash and clout. But for most of us, I imagine our participation in ‘trauma culture’ arises from a desire for community, validation, and inclusion.

Sharing painful, personal experiences online and labelling them as trauma may help individuals validate their own experiences, while also granting access to the communities created around those labels. Social media provides the opportunity for connection and shared healing.

In my view, it’s worth questioning if the culture we’ve fostered around labelling and sharing trauma online actually helps us live with it. If we continually showcase our skeletons for the world to see, can we ever truly heal the pain within?

Fabienne de Cartier is a third-year student at Victoria College studying English and political science.

No comments to display.