With ChatGPT permeating our computers, artificial intelligence’s (AI) astonishingly rapid advancement has reached the forefront of the world’s attention. One question in particular is looming over everyone’s minds: how can we best deploy technologies such as AI so that they are safe and beneficial for everyone?

The Schwartz Reisman Institute for Technology and Society aims to answer just this. By focusing on the ethical and societal consequences of technology, the institute “seeks to rethink technology’s role in society, the needs of human communities, and the systems that govern them.” In nine sessions with 23 speakers, in fields spanning computer science, psychology, law, economics, education, philosophy, media studies, and literature, the third annual Absolutely Interdisciplinary Conference, on June 22, 2023, put a wide variety of perspectives into the conversation to better understand how AI can promote human well-being.

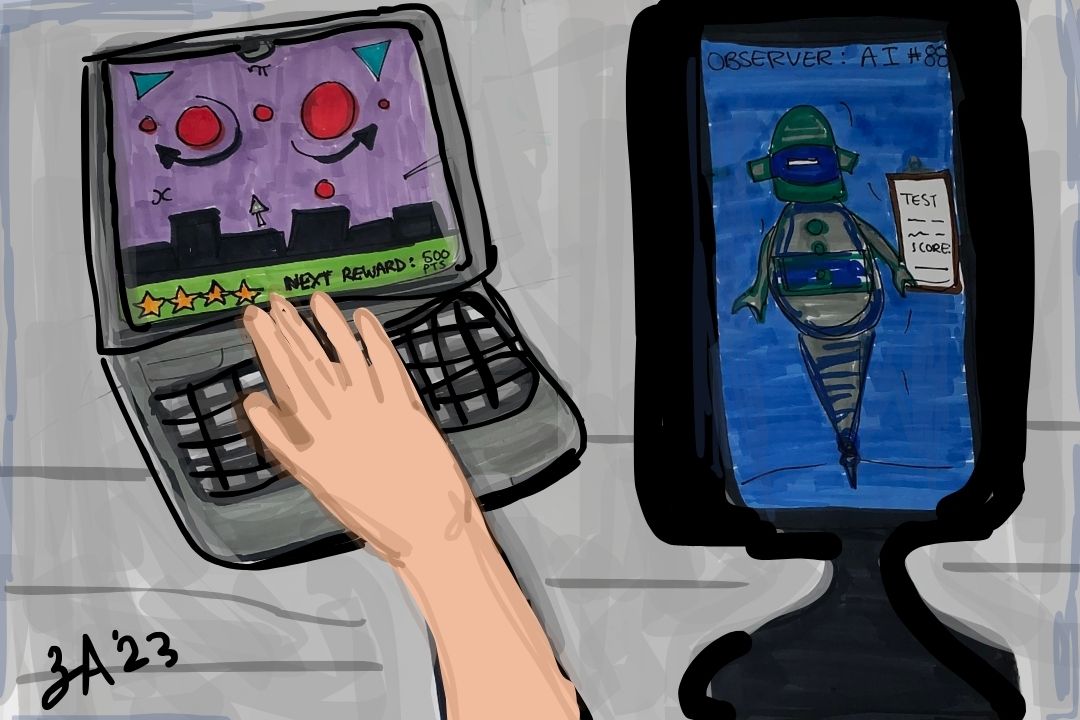

In a session titled “The Reward Hypothesis” at the conference, Richard Sutton joined Julia Haas — a senior research scientist in the Ethics Research Team at an AI company called DeepMind — and moderator Gillian Hadfield — the director of the Schwartz Reisman Institute for Technology and Society — to discuss the reward hypothesis and how it can advance our understanding of human decision-making.

The reward hypothesis

Almost 20 years ago, AI research pioneer Richard Sutton presented his reward hypothesis: “What we mean by goals and purposes can be well thought of as maximization of… a received scalar signal [or reward].” This means that the desire to maximize some kind of reward, whether social or material, drives all our goals and purposes.

The discussion opened with this question: is the reward hypothesis a good model for understanding human behaviour?

Sutton believes it is. “The powerful part of [both human and artificial] intelligence is not the ability to mimic people but the ability to achieve goals,” he claimed. More specifically, intelligence is the computation that allows us to achieve goals.

From this definition, Sutton hypothesizes that “intelligence, and its associated abilities, can be understood as subserving the maximization of reward.”

Sutton has considered possible opposing claims that reward is not enough to capture the full extent of human intelligence. Yet, he does not see a better alternative to the reward hypothesis for discussing human motive. The formulation of goals as rewards not only forms the basis of classic AI theories such as artificial cognition, but also helps us model decision-making in the fields of neuroscience, psychology, and economics.

Haas agrees that the reward hypothesis has changed our understanding of the mind. But while Sutton’s reward hypothesis only applies the concept of reward to our goals and purposes, Haas presents a stronger thesis — that the mind computes and continually evaluates features of our environment in terms of reward. Essentially, she claims that “we perceive the world conditional on our goals,” meaning that we tend to remember things to which we attribute higher rewards, whether social or material.

How the reward hypothesis might guide decision-making

Extended to questions in morality, Haas’s theory claims that experiences of right or wrong are merely attributions of reward and value. This interpretation allows morality to be quantified in terms of reward, allowing a greater understanding of the application of morality to artificial intelligence.

The conversation then turned to the ability of the reward hypothesis to inform our understanding of morality and ethics.

For Sutton, the reward hypothesis is essential to the development of morality. “Good and evil,” Sutton claimed, “are about the sum of upcoming reward… so basically, [moral decisions are] all hedonism, but value functions make it hedonism with foresight.” Sutton defines value functions as “predictions of [a] reward,” upon which all efficient methods for decision-making rely.

Haas posits that moral cognition is full of errors. She claims that we should not use the reward hypothesis to completely guide a theory of ethics. But Haas does not think we should discard the reward hypothesis entirely when it comes to morality. We can use the reward hypothesis to understand the mechanisms behind our perception of something as right or wrong.

Overall, the session’s participants were left with an enlightened understanding of how AI can be trained to make intelligent decisions, and perhaps even a few insights into how we make ethical and value-guided decisions as humans.

No comments to display.