This article contains spoilers.

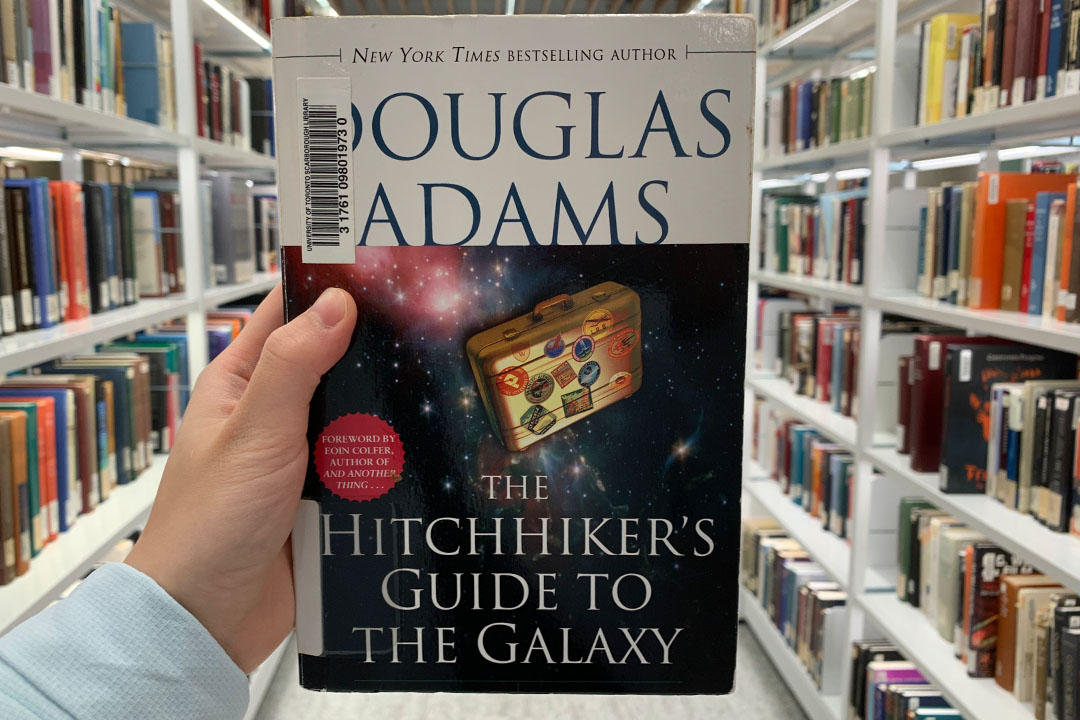

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is a veritable masterpiece of science fiction. It’s ostensibly random but somehow still coherent, and the events are hilarious in a delightfully clever way. It’s what you might imagine to be the result of putting a witty, extremely creative scientist in a room and telling them to write whatever comes to mind.

The novel begins on Earth, where the story’s main character, Arthur Dent, is fighting to keep his house from being bulldozed to make room for a highway. The demolition crew slated to carry out this task is led by a shabby man who, from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm, seems to dutifully restrict his attention solely to matters of bulldozing.

While Arthur may understand this, he is not sufficiently empathetic with this man’s devotion to sanctioned destruction to step aside and watch his home be flattened. Hence, they arrive at an impasse.

If you’re thinking that the aforementioned dilemma seems overly mundane for a novel about the galaxy, you would be right. The much bigger problem is that the Earth itself is set to be bulldozed on the same day for a galactically analogous reason: to make room for a highway.

After Arthur escapes Earth right before it’s destroyed, the problems he faces become increasingly inventive in a crescendo that culminates in his near death at the hands of mice — more on this later.

Arthur has just seen his planet incinerated and is now aboard a spaceship called the “Heart of Gold” with a group of whimsically-named aliens and their hopelessly depressed robot, Marvin. They are travelling to a planet called Magrathea.

Travelling the lightyears separating Magrathea from Earth would be an unsolvable problem for most spaceships, but luckily, the Heart of Gold is no ordinary spacecraft. Its engine operates based on the laws of “improbability physics.”

Explaining this complicated, mostly fabricated branch of physics in a few lines would be infeasible, so we’ll just concern ourselves with its application to the spaceship. The Heart of Gold is simultaneously everywhere at once, much like an electron. This seems to be a play on quantum superposition, a principle in quantum physics in which a subatomic object — like an electron — is in multiple states simultaneously until measured.

The Heart of Gold contains an engine that allows the crew to artificially shift the probabilities of a ship being in certain positions. Through the Improbability Drive, it becomes perfectly likely for the ship to be, say, across the galaxy at Magrathea.

When Arthur et al. finally reach Magrathea, they find it not only inhabited but also quite busy. It turns out that Magrathea’s economy is based around the luxury planet-building business, and they were recently assigned a new planet to build: Earth Mark 2.

Who, you might ask, would be willing to spend the money to create another version of a planet that was only recently determined to be less valuable than a highway? Well, the mice, of course.

It’s common knowledge in most regions of the galaxy, the book explains, that mice are the most intelligent species on Earth by a considerable margin. Arthur learns that they’ve been deceiving humans for thousands of years with the whole inane squeaking charade, so that they could monitor their experiment, Earth. Our planet’s premature destruction had forced the mice to restart their 10 million-year computation by building another one.

When the mice hear of Arthur’s arrival on Magrathea, they invite him to a private meeting where they explain all this. Arthur is given the opportunity to sell his brain, which the mice believe may hold the answer to their experiment. Rudely enough, he is not offered a replacement brain.

In the interest of keeping his head firmly attached to his neck, Arthur and the rest of the crew, the aliens, make a rush for the Heart of Gold. All members, including the galactically miserable robot Marvin, make it off Magrathea safely.

And then they go for lunch.

I don’t think it’s at all an overstatement to say that The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy sparks the imagination. It targets that voice in your head that occasionally encourages you to put popcorn kernels in pancakes, so that they might be able to flip themselves. And if you’ve never considered flipping pancakes this way, perhaps a lesson in improbability physics would do you good.

No comments to display.