Did you live in fear of your lab partner unleashing a biological weapon upon your school? Do you remember him complaining about high school being a microcosm of the cesspool that is human society? Imagine, instead, that your high school is the entire planet, and he successfully wipes out the human race.

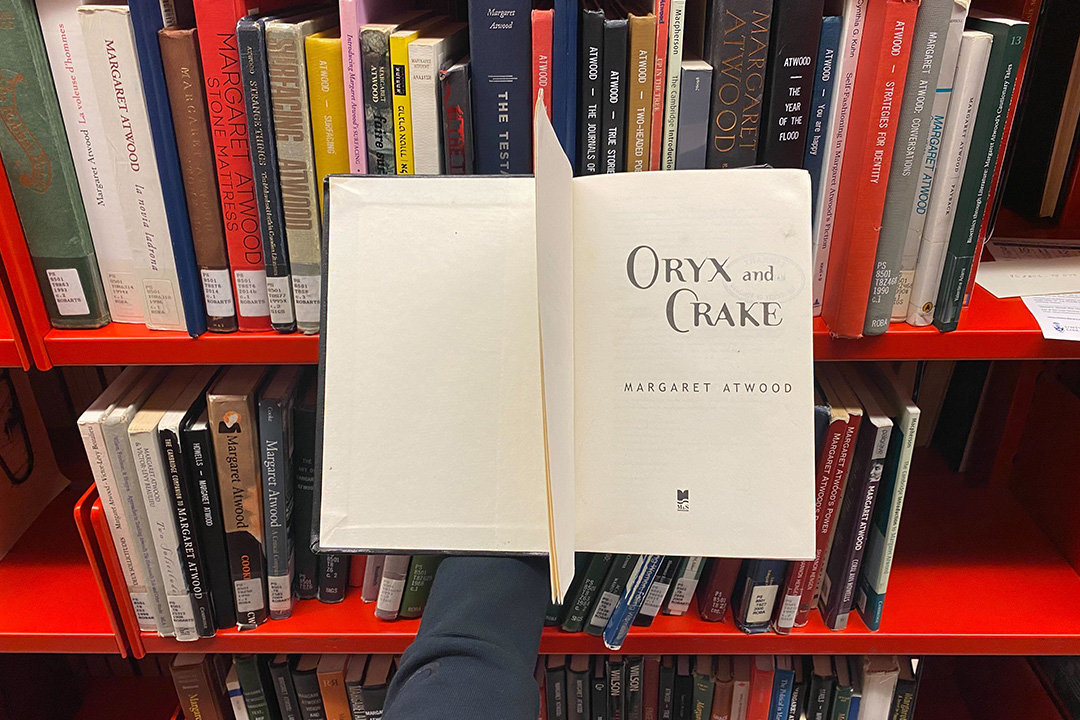

If this was a compelling speculation exercise for you, then Margaret Atwood’s 2003 Oryx and Crake might be your next favourite book!

Jimmy’s world pre-apocalypse and pre-Crake

We are introduced to Snowman — previously known as Jimmy — a young man in early adulthood who has begun to resemble a decomposing corpse. Our human protagonist lives in a post-apocalyptic world where the only other human-esque life is the “Crakers”: a species manufactured by Jimmy’s friend, Crake, to come in as many colours as scented soap bars. Through flashbacks, we learn about Snowman’s past life as Jimmy and his relationships with Crake and with a child named Oryx. For someone who shares half the novel’s title, however, Oryx’s voice is unheard.

Pre-apocalypse, Jimmy grows up in a dystopian caricature of the present-day world. Corporations have taken over, and elite scientists working in these companies live in gated communities called “Compounds.”

We see Jimmy bounce from Compound to Compound throughout his childhood: from OrganInc — so called because they sell organs, and they’re organic — to NooSkins — as in “new skin” — and finally to RejoovenEssence — the place where the tragic fate of the planet takes place.

Atwood links NooSkins with vanity; it is plastic surgery on steroids. In the novel, characters can replace their skins with a literal new one — a prophetic insight before the pre-Kardashian world of 2003.

However, NooSkins in Atwood’s novel only criticizes plastic surgery without acknowledging its virtues. In our present-day real world, the closest thing to NooSkins has been a technology driven by altruism. Skin grafts help burn victims and children with butterfly skin — a condition that results in a fragile epidermis.

Further, the book adopts a sneering, elitist attitude toward genetically engineered organs and food. Genetically engineered food aims to help create a more sustainable form of nutrition — would you rather eat factory-farmed chickens who’ve lived in unendurable conditions? Also, xenotransplantation — transplantation between species, especially between genetically modified pigs and humans — carries the prospect of helping people who might be stuck on waiting lists for donor organs. In the novel, these technologies are used in excess to criticize scientists’ egotism.

The Oryx and Crake society is littered with genetically engineered creatures, such as transgenic pigs for organ harvesting called “pigoons” and domesticated cross breeds between raccoons and skunks called “rakunks,” because the human condition is the irrepressible urge to pet a furry creature.

Atwood is critical of the overzealous scientific community playing god, but the story fails to recognize that this very community is responsible for modern medicine and lengthening the average lifespan. Transgenic animal models are used to study the effects of enforcing the expression of specific genes, like oncogenes — which are susceptible to causing cancer if mutated — or tumour suppressor genes — which regulate cell division and other processes implicated in cancer.

Jimmy and Crake

An adolescent Jimmy forms an everlasting friendship with Crake, a fellow human. After high school, Crake heads off to the prestigious Watson-Crick Institute to study biology, and Jimmy to the much less illustrious Martha-Graham to study the only utilitarian way English can be used — marketing.

After a series of monotonous jobs, Jimmy reunites with Crake, who offers him a job at RejoovenEssence to work on the Paradice Project. In this major project, Jimmy helps advertise pills that would rejuvenate youthfulness and sex drive but also sterilize the masses — the latter part of its purpose not to be disclosed to said masses.

While Atwood might have included this detail as a criticism of the gruesome history of scientists withholding information from participants or deceiving them in participatory research, it might also be seen as another criticism of mass marketing and how governments and corporations conceal information from civilians.

The second major project spearheaded by Crake is creating a superhuman species — the Crakers, the legacy of humanity. This might be Atwood’s criticism of the god-complex scientists suffer from — Crake acting as a god by creating a new species named after himself. They are the creatures that stay after humanity has perished post-apocalypse. Present-day Jimmy, Snowman, watches over the Crakers.

A cautionary tale turned comedic

Atwood might have been hoping to caution the reader about the effects of unmoderated plastic surgery, genetic engineering, and other science technologies, as well as how capitalism leads to science being used for corporate benefit.

However, this point wobbles on the weak legs of underdeveloped characters and a melodramatic ending. Should I be fearing corporations misusing science or a manic scientist massacring humanity?

Crake represents a philosophical dilemma regarding how messed up humanity is; he poses an important question — are we worth saving? Should we just be replaced by a better, kinder species? But Crake’s ability to mass-exterminate society all by himself just to replace us with humanoid creatures that smell like scented candles ends up being more comedic than cautionary. The critical potential of the novel is undermined by its childish, self-serving characters and the trivial outcomes of their actions.

New technology can lead to social disparity because there is always a question of who has access to this science and its applications. But isn’t the problem with whose hands steer the vehicle of science inquiry to devastation? Must humanity leave its misery in the hands of an uncaring divine being? Why should we not “play god”? Science is a deity of crossroads: it only leads us down the path we choose.

I would give this book 1.5 stars out of five — pretty prose but thematically unsatisfactory. As for speculative fiction: next time, the author should speculate on something else.

No comments to display.