When we consider geography, we often forget that it’s an act of imagination. The national and international borders that we draw rely on geopolitical machinations out of our reach. The province that we live in connects people across immense swathes of land, most of which we will never see. Even the city is an imagined community — when was the last time that you visited a neighbourhood outside of your normal routine?

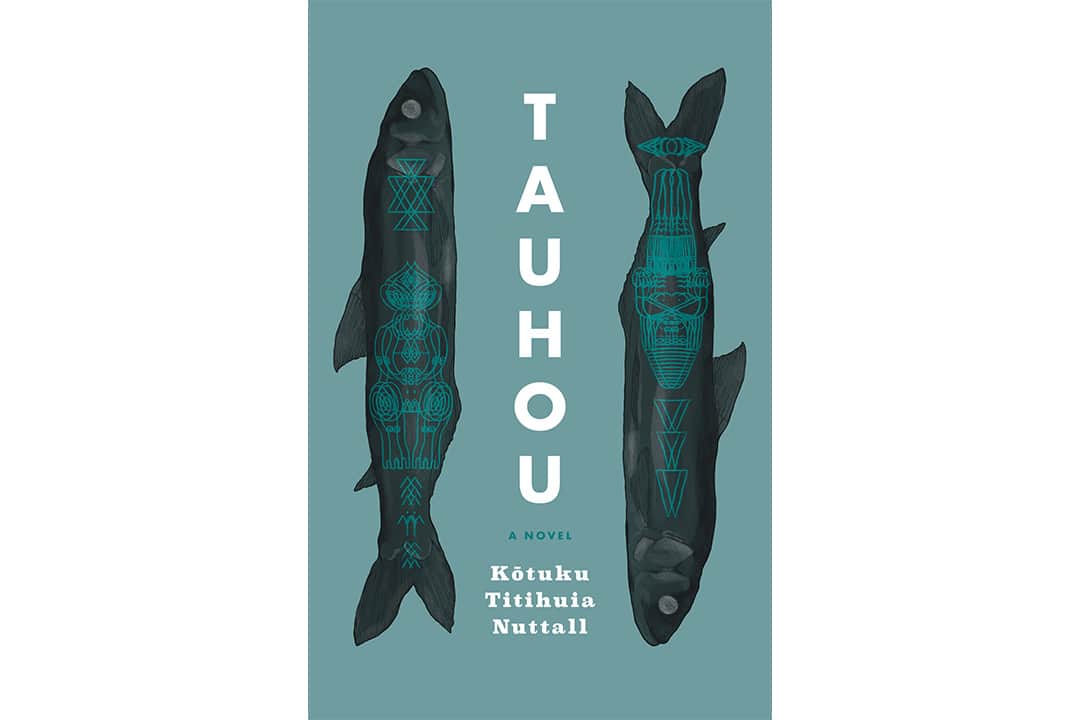

Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall’s debut novel Tauhou stretches the geographic imaginary beyond land and into generations — not just through time or history but by envisioning land through past, present, and future lineages. She begins with a creation poem that places the two islands of her Coast Salish and Maōri heritage — Vancouver Island, Canada and Aotearoa, the Maōri name for New Zealand — side by side. She explores stories from these lands individually, as well as stories that connect them, without regard for chronology.

Although Tauhou could technically be described as a collection of short stories, I prefer to think of it as one narrative, constantly iterating over the same islands in different ways. One of the most powerful ways that Nuttall articulates this is through the book’s full title — Tauhou: A Novel. In the description of the book published on the website of Canadian publisher House of Anansi Press, it says: “Dear grandmother, I am writing this song, over and over again, for you. I am a stranger in this place, he tauhou ahau, reintroducing myself to your land.”

Each chapter is a reintroduction, and before you have time to feel jilted by the departure of a story, Nuttall introduces another one — another perspective, another language, another way to mould similar experiences into something new. While reading it, I got the distinct feeling that the emotions shown in each story could be woven into a tapestry of one person’s life.

In Tauhou, Nuttall imagines what historical dynamics between them could have looked like and what future relationships could be. By leaving parts of the islands’ history ambiguous — particularly the extent to which settler colonialism had existed in the world — she was able to explore Indigenous futures in a unique way, imagining alternate settings in urban areas, on a reservation, and in villages.

One setting that stood out in my mind is one of the first ones described in the book; a woman named Hīnau describes her commute to work, travelling from her home in an above-water condo community on stilts to her job at the tribal propaganda office. Nuttall’s frank yet imaginative prose immediately allows a reader to see the beauty and brutality of such a landscape. This intriguing setting was not just a backdrop, as Nuttall was able to deftly weave Hīnau’s personal relationship to the land as well as her interpersonal relationships into descriptions of the landscape itself.

And here lies Nuttall’s greatest strength: her ability to write about the ways that people care for each other and themselves. At a point in the novel, Nuttall contrasts the varied ways in which two different characters practice tattooing. For Miro, getting tattooed is an escape — distinctly metropolitan, somewhat impersonal but not unkind, an exercise in tolerating pain through silence and stillness. She explicitly describes the process as violent, yet simultaneously craves that violence “until it happens, and then she’s waiting for it to stop.”

Immediately after, we are shown Hīnau, who chooses to get tattooed with “old world style” designs after seeing the style on many of her colleagues. She’s tattooed in the artist Camas’ home. Camas offers her food, and gently contests her use of the word ‘traditional’ to describe what she wants, using a skin-stitching method instead of a tattoo gun.

The juxtaposition of these vignettes itself contains acceptance. Even with two vastly different outlooks on tattoos, they’re an emotional release for both Miro and Hīnau, regardless of whether their tattoos have an explicit connection to their cultures. The care that Camas shows Hīnau in the novel shows that even the briefest of connections can offer safety and comfort. Nuttall explores the complexities of cultural alienation, connection, and familial trauma, gently turning over each rock and examining the mud and bugs and moss on them.

As much as this novel is about culture and land, it is also about love and family. The overwhelming majority of the romantic relationships portrayed in Tauhou are between women who have varying relationships to their sexuality — but notably, never rejection or disgust. The tension and love within their relationships were explored in conjunction with a fundamental acceptance of them. As someone who is bisexual, it was nice to be able to delve into the intricacies of the relationships in this way — in a story that allowed lesbian relationships to exist as they are and didn’t try to make them seem like straight ones in the process.

Through recreating geographic boundaries, Nuttall has found a way to understand the complexities of a person’s relationship to their culture spatially. Worldbuilding that focused on cultivating this theme, rather than geographic or historical realism, allowed her to expand into different stories without creating a disjointed work, constructing an emotional depth that has left a profound impression on me since I read it. I recommend Tauhou because it masterfully weaves together stories, traversing a wide cast of characters and a range of time periods without leaving you in the lurch.

No comments to display.