A groundbreaking finding published this August in Proceedings of the Royal Society B is revolutionizing how we think of ancient life. Researchers from U of T have identified the oldest fossils of a free-swimming jellyfish, which dates all the way back to about 505 million years ago.

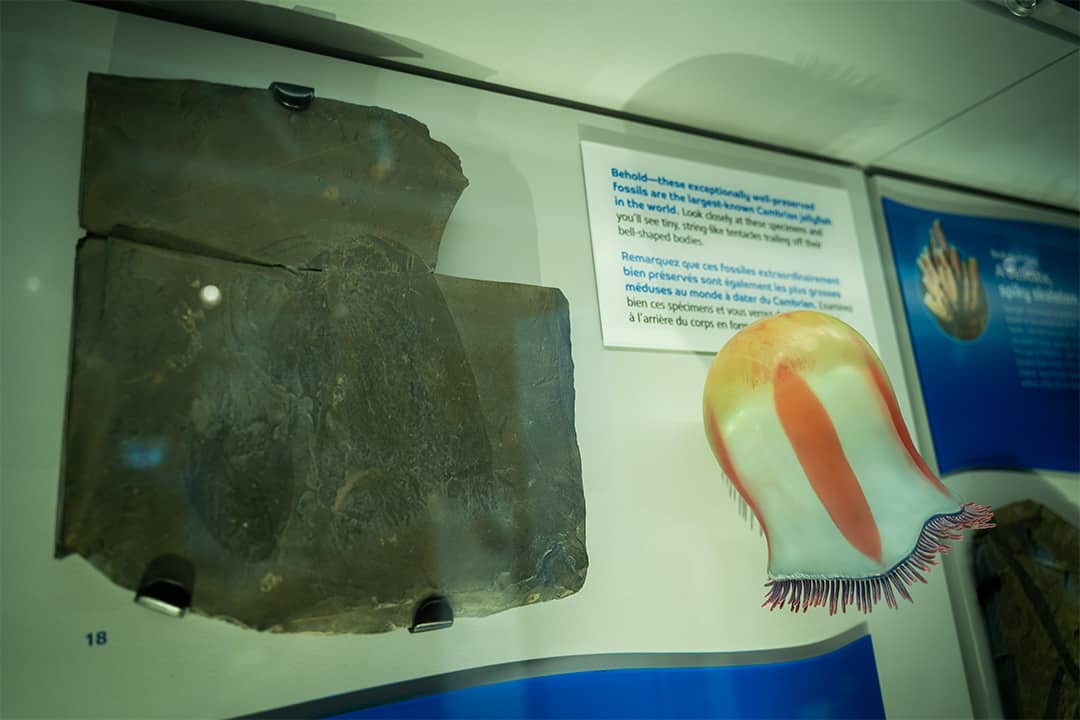

These exceptional fossils, now nestled within the hallowed halls of the Royal Ontario Museum’s (ROM) Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life, shed light on an enigmatic period when life on Earth was starting down its path toward complexity, offering invaluable insights into the evolution of not only jellyfish but also the broader marine ecosystem.

In U of T’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Joe Moysiuk, a PhD candidate, and Jean-Bernard Caron, an associate professor in the Department of Earth Sciences, looked into the fossils, which come from the Burgess Shale of British Columbia’s Rocky Mountains. This area is renowned for preserving a remarkable time in the history of life known as the Cambrian period. The Cambrian period is a timeline in geological history when an explosion of diverse and complex life forms happened over 500 million years ago.

The collaborative efforts of the researchers brought to the spotlight a total of 182 fossils that have sent shockwaves through the scientific community and garnered global attention from media outlets, including CNN, The Guardian, CBC News, and New Scientist.

Behind the Burgessomedusa

These fossils were actually discovered in the 1980s and 1990s during expeditions led by Des Collins, then-curator of the invertebrate palaeontology collections at the ROM, but it wasn’t until a colleague of Caron and Moysiuk, Justin Moon, led a study on the early evolution of jellyfish-like animals as part of his graduate work at U of T that these fossils got the attention they deserved.

In emails to The Varsity, Moysiuk explained, “[Moon]’s project focused on the early evolution of cnidarians, the group of animals with stinging cells including jellyfish, anemones, and corals. Describing the oldest jellyfish was therefore a very important step for him.”

“Although these fossils were discovered 30-odd years ago, they had never been formally described or studied. There’s always a tension between the urge to wait to see if more fossils can be discovered and just getting the work out there. After all this time, it’s exciting to finally give these fossils the attention they deserve.”

These fossils have unveiled an entirely new species of jellyfish named Burgessomedusa phasmiformis. In general, jellyfish are Medusozoans, a major part of Cnidaria. The new jellyfish genus was newly named Burgessomedusa because the fossils were found in the Burgess Shale — hence the Burgesso — and this genus, like other Medusozoans, has stinging tentacles like the mythical snake-haired figure Medusa — hence the medusa.

As it gracefully moved through the prehistoric oceans, this giant ghostly form resembled the iconic ghost from the game Pac-Man. The etymology of the phasmiformis species name is from the Greek word “phasma” and the Latin word “forma,” referring to the phantasmal form of the jellyfish’s umbrella.

These jellyfish, characterized by bell-shaped bodies reaching up to 20 centimetres in height — just about the same length as a No.2 pencil — and with around 90 tentacles, were not mere drifters but likely active and efficient predators.

Moysiuk wrote to The Varsity, “Burgessomedusa is large for a Cambrian animal. Our own ancestors, the earliest fish, were no bigger than a little finger at this time. We also think Burgessomedusa was a predator since modern jellyfish and their relatives use their stinging cells to capture prey. We don’t know for certain what these jellies were feeding on, but we do have one specimen that shows some ancient crab relatives inside its bell, which could be evidence of predation.”

Reconstructing history

The fossils presented an interpretive challenge. Moysiuk explained in an email to The Varsity, “Fossils from the Burgess Shale, including Burgessomedusa, are highly compressed. This can make them a challenge to interpret and reconstruct in 3D. Fortunately, we had a large collection of about 200 specimens, some of which were buried at different angles relative to the shale bedding plane.”

Comparing these specimens proved pivotal in comprehending the 3D geometry of these creatures. Moysiuk says that his team’s construction of the jellyfish’s shape might change if scientists were to discover a specimen perfectly preserved in either a ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom-up’ view.

The significance of this discovery goes far beyond its extraordinary age. Soft-bodied creatures like jellyfish are often elusive in the fossil record. Notably, jellyfish are composed of 95 per cent water. Because of this high water content, fossilization is extremely rare.

Thankfully, the Burgess Shale is a remarkable store of well-preserved, detailed fossils of delicate structures such as jellyfish, which usually disintegrate before leaving an imprint. This allows scientists a rare glimpse into the ancient marine life that thrived during the Cambrian period.

Caron emphasized the significance of these findings. In a release from the ROM, he said, “Finding such incredibly delicate animals preserved in rock layers on top of these [Burgess Shale] mountains is such a wondrous discovery. Burgessomedusa adds to the complexity of Cambrian food webs, and… these jellyfish were efficient swimming predators. This adds yet another remarkable lineage of animals that the Burgess Shale has preserved, chronicling the evolution of life on Earth.”

As the oldest definitive free-swimming jellyfish ever found, Burgessomedusa paves the way for further exploration into the evolution of marine life. Not only does the discovery enrich our understanding of the Cambrian period, but also enables us to reflect on the intricate history of life.

Moysiuk and Caron’s study was funded by doctoral fellowships from the University of Toronto, an Ontario Graduate Scholarship, and a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

No comments to display.