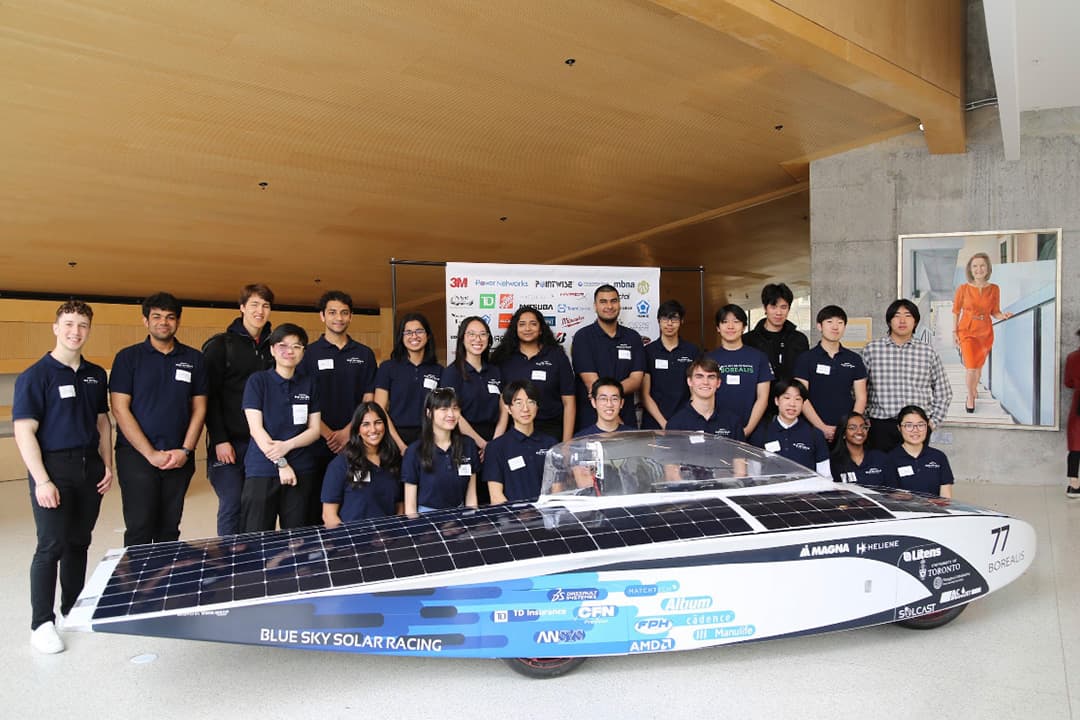

U of T’s own solar-powered racing team, Blue Sky Solar Racing, is currently in Australia with their car — the Gen 11: Borealis — preparing to race in the World Solar Challenge (WSC), a 3000-kilometre route from cities Darwin to Adelaide.

Set to begin on October 20, the race will mark the culmination of four years of work for a team that includes over 50 U of T students.

Building the Borealis

The process of designing the Borealis began with Blue Sky’s aerodynamics team, who created a simple conceptual design for the car. Afterward, Blue Sky’s other technical subteams joined in and designed their own systems, including the car’s suspension and electrical systems. At this point, Blue Sky had various designs they were considering and had to decide which was the most efficient and feasible to manufacture.

Next up in the process was the details stage — this is where the team got into the nitty gritty calculations. The mechanical team ran simulations to ensure the car’s safety, and went through load calculations, while the electrical team focused on making their printed circuit board designs. At the same time, the array subteam worked to find the best setup for the car’s different photovoltaic cells — devices that convert light into energy, also known as solar cells — to make the car as efficient as possible.

After this, the long and complex manufacturing stage began, in which the fabrication team spent more than a year creating the Borealis. Rigorous testing followed, as the team ensured the car was ready for the Australian Outback, where it went via ocean freight.

Teamwork, coordination and cooperation

Waiting at the port was the Blue Sky Solar Racing team, headed by their two team managers: Nikitha Manickam, a fourth-year mechanical engineering student, and Aria Qadir, a third-year mechanical engineering graduate student.

Manickam deals with all the logistics of the team: dealing with insurance, testing locations, managing permits and race regulations, as well as timelining the entire project. Meanwhile, Qadir operates as the chief engineer, supervising all of the technical sub-teams, including aerodynamics, mechanical, structural, array, electrical, and strategy. Crucially, he also serves as the bridge between the different teams, ensuring coordination.

Coordination and cooperation were always a focus for the two leads. Creating a support system was essential to handle the challenges that come with being part of Blue Sky Solar Racing. Team members are given important tasks and responsibilities for specific parts of the process, from design to manufacturing.

Conflicting opinions was another challenge. Having an open environment in which they could make decisions as a team was crucial to moving forward. The team had to create a close-knit community for the unique challenges of the development cycle.

Challenges in the process

For over 25 years, the cycle for WSC teams to build a car and participate in competitions has been two years long. That cycle changed when the 2021 WSC was cancelled due to COVID-19. Development never stopped for Blue Sky, who, following the news, had their sights set on the 2022 American Solar Challenge (ASC). Thus, Borealis was built with ASC regulations in mind — but unfortunately, it wasn’t finished in time to race in the ASC.

With their sights returning to the 2023 WSC, the team had to remodify the car. The team had to backtrack to the design stage to ensure that Borealis complied with WSC regulations. For example, the shape of the body of the car — the ‘aerobody’ — had to be modified to still be aerodynamic, but now with a license plate on the back, as required by the WSC. Alternatively, the ASC had stricter safety regulations, meaning Blue Sky had to replace sections of the car to make Borealis as efficient as could be for the WSC, which wasn’t as restrictive.

Even without the pandemic, the team already had their hands full with how they would handle the Outback. Heat exhaustion for the drivers was a big concern, as air conditioning couldn’t be incorporated into the car due to the loss of power it would cause. The lack of a consistent telecommunications signal also created additional logistical challenges to ensure the team could communicate throughout the race.

Ready to compete

Nevertheless, in spite of all the challenges presented by COVID-19, racing regulations, and Australia itself, Blue Sky Solar Racing and the Borealis are ready to compete.

Compared to previous generations of Blue Sky cars, this car is lighter, meaning it’s more efficient. Reducing the width allowed the team to create a car with a lower drag coefficient, meaning the Borealis is also faster. The car is more powerful, meaning it can travel further, thanks to a jump in the technology of photovoltaic cells.

With the race set to begin on October 20, nerves on the team are high. Ending up in a good position will ensure the team acquires sponsors for the next development cycle.

“You just look back at all of the amount of time… sleepless nights, countless hours that [the team] have spent [on] the car. You want to end up in a good position,” Qadir said. That isn’t an easy task, especially considering that the lengthened development cycle meant the team lost skills and knowledge provided by previous team members who graduated.

Many other teams competing in the WSC are made up of master’s students who take a year off from school for the project. However, Blue Sky Solar Racing is made up of mostly undergraduate students who do the project and school full-time.

“It’s kind of like a ‘Holy crap’ moment, where you realize that you’re balancing these two things that take up so much of your time,” Manickam said in an interview with The Varsity. “The [fact] that we’re able to get the car out was like… we actually pulled that shit off?”

The team did pull it off, and now all that’s left to do is race. You can follow Blue Sky Solar’s journey on blueskysolar.org, which shows the team’s live location, or keep up with the team on their Instagram and LinkedIn.

No comments to display.