Content warning: This article discusses death and violence.

On September 19 — approximately a year after the death of 22-year-old Mahsa (Jina) Amini in the custody of Iran’s ‘morality police’ — U of T community members and members of the Iranian diaspora gathered in a classroom at the Ramsay Wright building to commemorate Amini’s death and the protest movement that it sparked. During three hours of speeches and discussion, attendees discussed resistance against Iran’s current authoritarian regime and what Iranians inside and outside of the country envision for the country’s future.

The event — called “Mahsa Amini: the Spark of a Revolution” — was the latest in a series of community events hosted by the University of Toronto Students for a Free Iran (UTSFI) over the last few months. According to an email from organizers, they hoped that the evening would “shed light on the reflections and lessons drawn from the Iranian people’s enduring resistance, as well as their relentless fight for justice and freedom over the past year.” Organizers estimated that over 100 people attended the event.

The evening opened with a video from the UTSFI, a retrospective on Iranian activism against the current regime over the past year. Four activists from the Iranian diaspora then spoke to the audience about their experiences resisting the Iranian regime. Speakers included Hamed Esmaeilion, former president and spokesperson and current board member of Families of Victims of Flight PS752; Zarrin Mohyeddin, a long-time political activist; Kaveh Shahrooz, a lawyer, human rights activist, and sessional lecturer and director of partnerships and legal counsel at UTM; and Mehrdokht Hadi, a community organizer who worked with the UTSFI for last year’s “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests.

After their speeches, each speaker hosted a question-and-answer period with the audience in both English and Farsi, and at the end of the event, Esmaeilion returned to the podium to answer still more questions. Many audience members participated in the discussions, and the event ran for an hour later than originally scheduled.

The speakers called on Canada to recognize the Iranian regime’s humanitarian abuses, including human rights violations related to the protests sparked by Amini’s death. Speakers and community members discussed what it means to organize resistance movements from the Iranian diaspora, and what a post-regime government would have to look like in the long term to be successful. Attendees also discussed what they want

to see in terms of support from non-Iranian allies.

Mahsa Amini’s death

The event came days after the one-year anniversary of the death of Kurdish Iranian woman Mahsa Amini — also known by her Kurdish name Jina — in a hospital in Tehran, Iran’s capital. She died on September 16, 2022, shortly after Iran’s ‘morality police’ — a unit that enforces the country’s mandatory dress code — seized her for allegedly failing to wear her hijab in compliance with the code.

Iranian officials have officially announced that Amini died of a heart attack due to pre-existing conditions. Her family, however, cite eyewitness accounts that police beat Amini while she was in custody, and her father has held the police responsible for Amini’s death.

After her death, massive demonstrations calling for an end to the theocratic Iranian regime began across the country and around the world.

The protest movement she sparked — which rallies behind the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” — is only the latest in a history of popular resistance against the current Iranian regime, headed by supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The current regime first came to power in the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which arose from resistance to the rule of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Following the revolution, a religious populist wing of the movement took over, instituting policies which limited women’s freedoms and cracking down brutally on dissenters.

Iranian women have driven resistance to the regime since its inception. Mohyeddin, who took part in anti-revolutionary resistance during the Iranian Revolution, fled Iran over 40 years ago, fearing retaliatory violence from the incoming regime. “I have been in this city for 44 years protesting and opposing the human rights abuses of the Islamic regime,” she told audience members at the UTSFI event. “It is not new for me.”

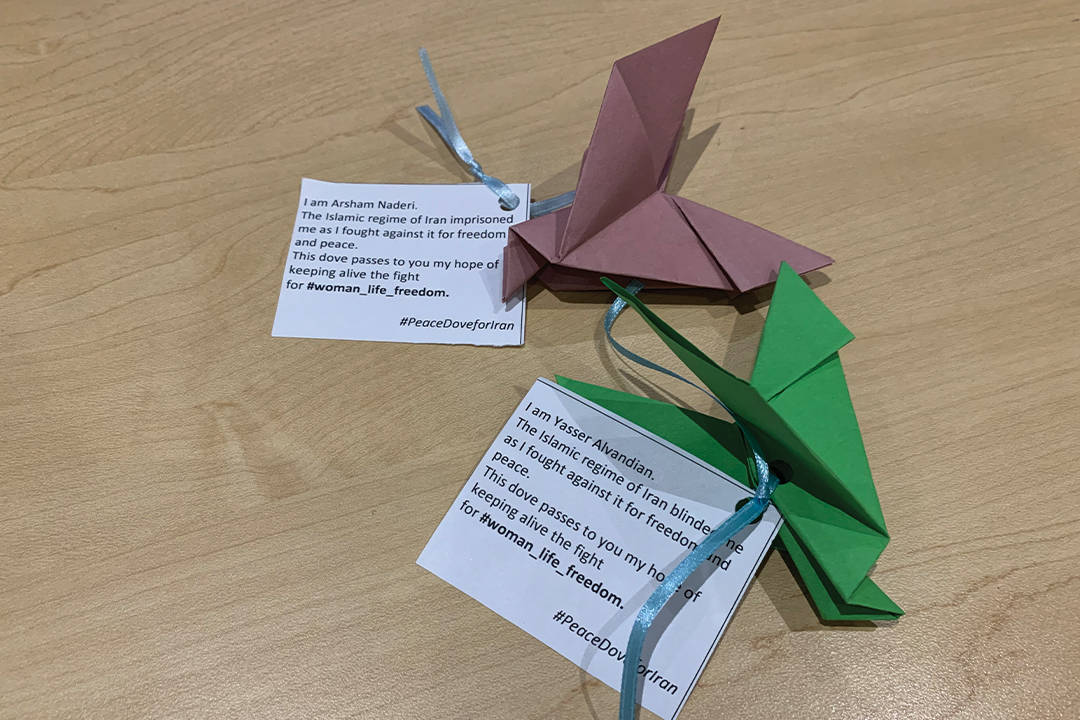

The event recalled others alleged to have been killed or injured by the current regime. Some of these include victims of the regime’s crackdowns on “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests after Amini’s death. The state has responded to demonstrations against the regime by shutting down protests violently, including by opening fire with pellet bullets on protesters in some of Iran’s top universities. During the course of the protest, it also launched widespread shutdowns of the internet and freely distributed information.

According to human rights associations from outside Iran, at least 500 people were killed during protests, and thousands were imprisoned. A report to the United Nations described the Iranian government’s activity since the protests as “the most serious human rights violations in the Islamic Republic of Iran over the past four decades.” Iran carried out more executions in 2022 than at any time in the past five years. The report described that the regime’s application of the death penalty has disproportionately targeted ethnic and religious minorities.

Active protests around the country have decreased significantly since the end of 2022, and in December, the Iranian government temporarily suspended the deployment of the ‘morality police’ force. Since July, however, the state has redeployed the force. On September 20, a day after the event, the Iranian government approved a new bill that lays out new punishments for women and men who violate legal dress requirements. Women who are found to violate Iran’s hijab requirements will be charged financial penalties, and serve prison sentences if authorities deem the violation part of an organized effort.

In the year after Amini’s death, figures who took part in the movement have also faced further suppression: journalists who covered Amini’s death and the subsequent protests have faced trial for allegedly “colluding with hostile powers.” The expulsion of dissenting academics from some of Iran’s top universities has spurred debate about whether their firings were related to the protests.

On the one-year anniversary of Amini’s death, organizers held protests in multiple cities worldwide. Meanwhile, the Iranian regime increased its police surveillance in Tehran and other Iranian cities around the anniversary to prevent further widespread protest movements. According to Kurdish rights group Hengaw, security forces have also been spotted in Kurdish minority regions of western Iran, where Amini was from and where residents staged large protests last year. The group additionally reports that the Iranian Revolutionary Guard detained Amini’s father in front of his home before the anniversary of Amini’s death.

Going forward

Still, Iranian reporters have observed changes in Iran over the past year. One of the most visible changes reporters have remarked upon since the advent of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests is the number of women navigating the streets of Iran without headscarves, even though Iran’s dress code hasn’t changed, and women are still required to wear the hijab under Iranian law.

The “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement also sparked the UTSFI’s formation, explained executive member Sara Shariati, a graduate student at U of T’s Institute of Medical Science, in an interview with The Varsity. Shariati explained that the organization aims to raise awareness among non-Iranians and foster discussions within the Iranian community in Toronto. Over the past year, the UTSFI has hosted speakers, other discussion events, and a rally on campus calling for action to liberate Iran.

Although speakers at the event discussed and condemned the actions of the Iranian regime during the protests, speakers often focused on building for the future. “To be honest with you, I see no point in trying to repeat the list of all the horrible things the Iranian regime has done and continues to do,” said Shahrooz in his speech. “If you’re here, you already know all that.”

Overall, speakers frequently emphasized how long-term planning, strengthening civil institutions, and prioritizing a representative movement with space for conflicting viewpoints will be vital to future advocacy. Shahrooz emphasized that the movement’s goals must be “freedom, equality, and pluralism.” He warned against the movement being taken over by “those who want to drown out voices that are different than theirs.”

“The path towards an absolute separation of religion and state is difficult, painful, and long,” Esmaeilion said. He noted that the ultimate goal he envisions is creating a democratic society in Iran, but that goal requires a lot of work building up Iran’s civic institutions.

How to get there

In her speech, Hadi advocated for better community organization within the Iranian diaspora. In an interview with The Varsity, she explained that the formation of the UTSFI was an example of how diaspora members can support each other’s organizations. She had coordinated with the group last year — when the UTSFI was working to organize a “Woman, Life, Freedom” protest and vigils for Mahsa Amini on campus — and helped connect them to resources and information. Now, she says, the group is “well known, [with a] good reputation,” and can empower other speakers with events like these.

Hadi described to The Varsity how important universities were as spaces to contribute to open dialogue and societal change, and called on Canadian universities to help out Iranian students fleeing the country by issuing them student visas. She added that she hoped student organizations would use their voices to call on the university and bring attention to Iranian issues.

Speakers asked for attention and advocacy in prioritizing Iranian issues from allies outside the Iranian community. For Canadians outside of the Iranian diaspora, and for members of the diaspora who know people in Canadian political office, Shahrooz had a specific message: Iranians aren’t looking for foreign military intervention but for governments to pay attention to human rights violations in Iran. He asked people to rally their networks to pressure national and international governments to acknowledge abuses committed by the Iranian government.

“The people of Iran have shown remarkable courage,” he said. “What we’re asking for is for the world to help Iranians free themselves.”

No comments to display.