On October 21, the U of T Faculty of Medicine hosted a hybrid conference titled “Toronto Neurology Update: Demystifying Neurology for the Non-Neurologist.” The event was directed by neurologists and assistant professors in the Division of Neurology, Dr. Peter C Tai and Dr. Jeff Wang.

The event featured six lectures by neurologists on various topics, aiming to present emerging insights into diagnostic methods and treatments for neurological disorders to physicians of diverse specialties — for example, geriatricians, emergency physicians, and family physicians — who would run into these neurological diseases or issues in their own practices.

Dizziness and vertigo

Dr. Paul Ranalli, a physician in U of T’s Department of Neurology, Otolaryngology and Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences, gave an insightful talk, seeking to make knowledge about addressing and diagnosing dizziness and vertigo accessible to the doctors and health care professionals in attendance.

Dr. Ranalli claimed that most vertigo disorders can be diagnosed through virtual appointments as long as the physician can differentiate between vertigo and non-vertigo dizziness, as well as the type of vertigo. Non-vertigo dizziness is an ambiguous term and can indicate other issues that might relate to cardiovascular disorders, medication or metabolic problems, psychogenic disorders, or multi-sensory deficits. A patient experiencing true vertigo will hallucinate movement — they will feel as though they are either spinning or accelerating linearly.

A key takeaway from his talk for me was the segment on anxiety and how it can imitate forms of vertigo. Because of the similarity in symptoms, doctors might misdiagnose vertigo as anxiety, which could lead to the patient experiencing even more anxiety regarding their condition, producing an unproductive spiral.

Sleep concerns

Dr. Brian J. Murray, the head of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre’s Division of Neurology and a professor in U of T’s Department of Medicine, gave a talk on sleep disorders. He explained that avoiding sleep for an entire night is the equivalent of having a blood alcohol level of 0.1 per cent, which equates to a state of impaired mood and driving skills.

Sleep deprivation has wide-ranging consequences, from mood problems and attention disorders to cardiovascular health issues and immune deficiencies. Dr. Murray highlighted the importance of asking patients with suspected sleep disorders about medications and substance use. This should be followed by assessing common medical or neurological disorders. Then, the physician should conduct common sleep tests to compare the patient’s sleep to the “normal.”

Regarding circumventing sleep insufficiency, Dr. Murray mentioned caffeine as the “ubiquitous” first resort for circumventing sleep disorder symptoms. We learned that one cup of coffee is only good to keep you attentive for an hour; up to three cups of coffee are effective per day, beyond which would not modify your state of consciousness.

A common theme in the physicians’ talks was their explanation of interesting therapies. Dr. Murray spoke about light therapy, which is used to treat a subset of sleep disorders known as circadian rhythm disorders and has a much more effective impact than melatonin.

Dementia

Dr. Benjamin Lam is a cognitive neurologist and clinical associate at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre who presented a talk on identifying dementia for inpatient consultation in primary care or the emergency department.

Dr. Lam walked us through the six cognitive domains: memory, visuospatial, language, executive function, attention, and social cognition. He explained how each domain links to different neurological conditions and, for each domain, what tests could be conducted to allow physicians to identify any underlying pathology relating to it.

However, not every identification test in these cognitive domains is ideal for each patient. For example, before physicians use tests that examine language fluency when testing for left frontotemporal dementia — damage to neurons in the frontal or temporal lobes — or progressive aphasia — damage to the speech and language-controlling regions of the brain — they must consider that the patient might have never been exposed to a particular word or spelling of a word they’re using.

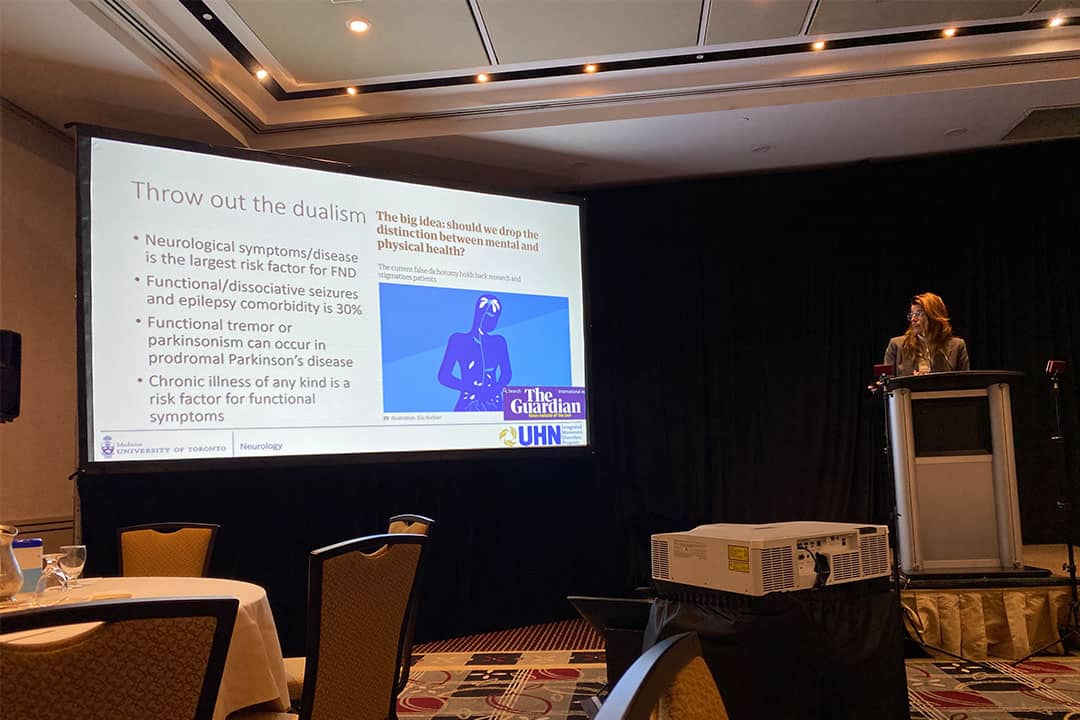

Functional neurological disorders

Dr. Sarah Lidstone is a neurologist and director of the Integrated Movement Disorders Program at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute. She educated the audience on how to recognize and diagnose functional neurological disorders (FND).

FNDs are defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Dr. Lidstone said that, when attempting to diagnose an FND, it is important to consider someone’s personality, coping, attachment styles, and control issues. She said, “Seeing somebody at a single crosspoint in time in your office doesn’t actually show you what that person’s nervous system has been exposed to.”

She also made sure to distinguish FNDs from feigning disorders, where the patient intentionally fakes symptoms, emphasizing that just because there’s no lesion doesn’t mean there’s no disorder.

In an interview with The Varsity, Dr. Tai said, “One of the aspects of ongoing practice in medicine is continuing medical education and enhancing your skills… as the field advances.” He went on to say that one of the responsibilities of neurologists is to educate community partners.

Clearly, the conference’s organizers accomplished this goal as physicians took the opportunity to learn about emerging and novel intervention strategies, symptomatic management tactics, and upcoming therapies.

Even as a student interested in pursuing a medical career, it’s important to become educated beyond your field of interest, as intersectionality and diversity are important in healthcare and science as a whole.