It’s a situation that legal clinic program director Sarah Pole is familiar with: someone comes to Canada as a minor, attends junior and high school in Canada, and makes plans — just like their classmates — to attend university. Then, they find out that they don’t have the legal documentation that universities require from them to apply.

Pole founded the Childhood Arrivals Support and Advocacy program, which operates within the legal clinic Justice for Children and Youth. The program focuses on providing legal aid to people with precarious immigration status who arrived in Canada as children.

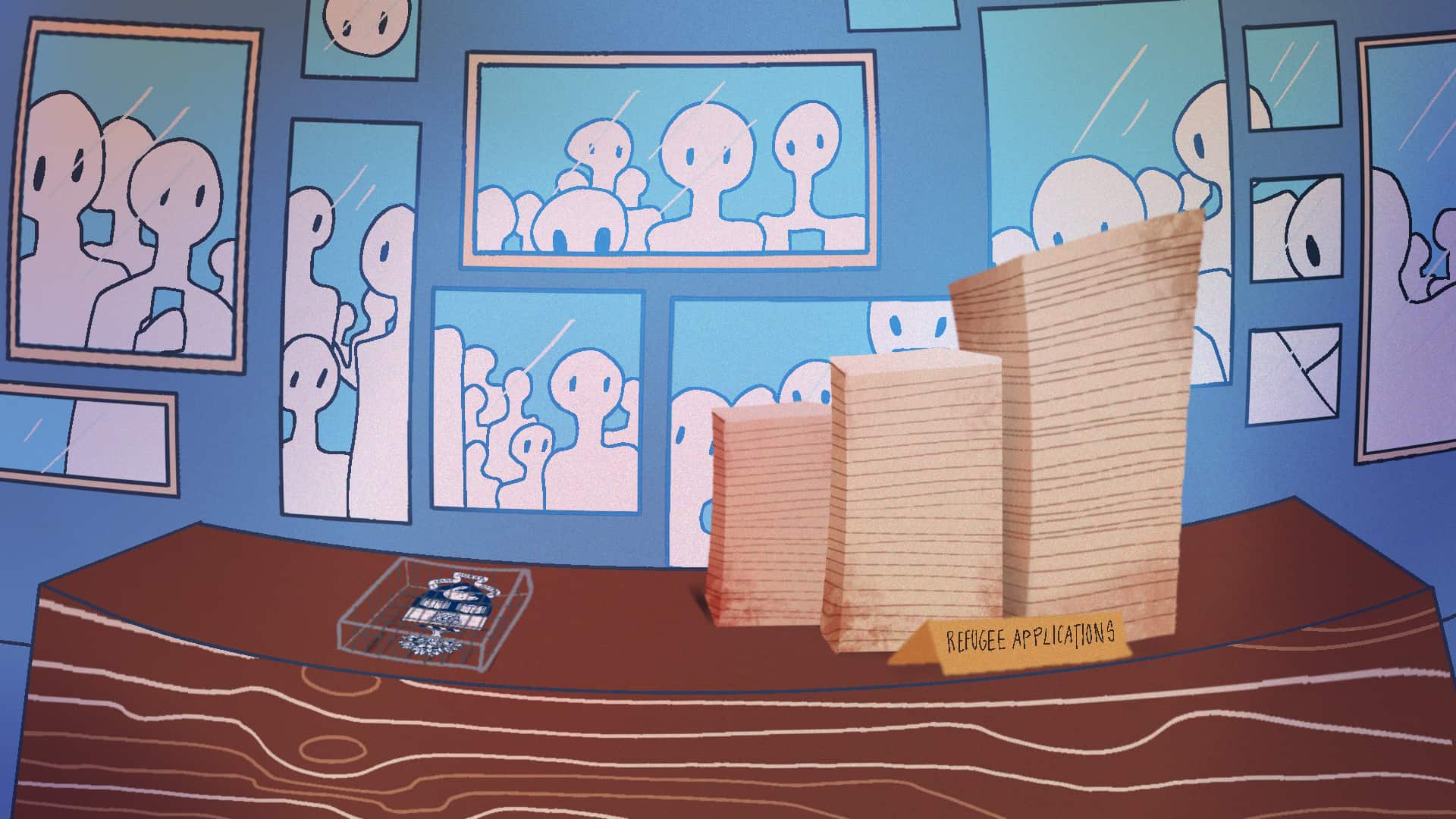

Thousands of students in Toronto alone graduate from Canadian high schools, only for fears of deportation — and the restrictive rate of international tuition — to bar them from enrolling in colleges or universities. It’s a tragedy that was part of what eventually pushed York University (YorkU) and Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) to implement what they call “Sanctuary Scholars” programs: systems that allow people without secure legal status in Canada to apply to the universities’ undergraduate programs without inviting threats of deportation, and without paying international fees, which can be as much as nine times higher than domestic fees.

Those behind the initiatives at YorkU and TMU have been pushing for U of T to follow their example. Advocates say U of T’s senior administration is dragging its feet.

If U of T is afraid that opening its admissions to students with precarious immigration status will get the university in legal trouble as they suggest, perhaps it can look to its fellow universities in Toronto for some guidance.

How access programs work

The “Sanctuary Scholars” programs — launched at YorkU six years ago and at TMU this fall — are available for applicants who, although otherwise qualified for university, have “precarious immigration status” — an umbrella term for anyone residing in Canada who does not have citizenship, Permanent Resident (PR) status, conventional refugee status, or a valid study permit from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

Tanya Aberman, an officer of both YorkU’s and TMU’s Sanctuary Scholars programs, told The Varsity in an interview that the reasons behind applicants’ precarious status can vary widely. Sometimes, they are individuals who came to Canada very recently. Sometimes, they are mature students who had been unable to get a university degree earlier in their lifetimes. Oftentimes, they are people who came to Canada as children and graduated from a Canadian high school.

Under normal circumstances, it can be next to impossible for these individuals to get a postsecondary education at U of T or at most other publicly funded universities and colleges in the country.

But if applicants who lack legal status want to apply to YorkU or TMU, they can meet with Aberman, who is the sole confidant about each applicant’s immigration circumstances. “They don’t then need to disclose their exact situation to anyone else,” Aberman explained. For students who fear deportation or other immigration-related sanctions, this part may be crucial in ensuring their security and even the security of their family members.

From then on, applicants simply go through administration under the umbrella label of “precarious immigration status.” The admissions board will no longer require proof of PR or a valid study permit. The student will pay domestic rather than international tuition rates. And if the applicant does not have access to documents like high school transcripts, the admissions board will work around it.

Aberman told The Varsity that she does not have full knowledge of the legal situation surrounding YorkU’s Sanctuary Scholars program. “There were some conversations with the province” when the program first launched, Aberman said — but aside from that, she is not aware that any serious concerns surrounding the program’s legality have come up.

The legal question

U of T faculty, students, and staff have said that the university’s hesitation here is unreasonable. Professor Alissa Trotz, director of the Women and Gender Studies Department, along with Audrey Macklin, chair in human rights law at U of T Law, are leading members of the working group that is calling on U of T to follow YorkU’s example.

“It’s not as if U of T would suddenly have its funding or its license yanked, [or be] thrown in some kind of National University Jail… that’s just not how things work,”

The working group consulted the law firm Blakes Law to issue a legal opinion on the matter, which the group received in November 2020. The group shared a copy of the opinion with The Varsity.

The Blakes opinion essentially predicts the kind and severity of legal risks publicly-funded post-secondary institutions in Ontario might face in implementing access programs like the Sanctuary Scholars’ programs. It draws three major conclusions on the legal consequences of implementing such a program.

First, Blakes concludes that post-secondary institutions like U of T admitting students with precarious immigration status are unlikely to get penalized under federal or provincial law. “There does not appear to be any provincial law or agreement requiring Ontario postsecondary institutions to refuse entry to applicants with precarious immigration status,” it reads.

There is a small chance that an attorney could interpret the law as forbidding post-secondary institutions from “assisting” people to study in Canada without valid documentation, Blakes notes. However, the opinion argues that there’s no precedent to bring an educational institution like U of T to court over this, and the government is unlikely to try. Blakes points out that it is not aware of any legal challenges on those grounds to YorkU’s program since it was established in 2017.

Even if they managed to succeed in doing so against U of T, Blakes argues, the university could raise a new challenge against the law itself for violating the right to life, liberty, and security of the person, as protected under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The result is essentially that many people in Canada are stuck in limbo for most, if not all, of their lives.

Second, Blakes considered the possible impact of such a policy on arrangements with the federal government. Universities like U of T enter into such arrangements regarding international students who come to post-secondary institutions in Ontario through the typical processes outlined by the government. The IRCC only issues study visas to international students admitted by “designated learning institutions” (DLIs), like U of T. DLI is a special designation given by the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities.

Would launching a Sanctuary Scholars program prompt the IRCC to revoke U of T’s designation, thus effectively barring it from admitting international students? Blakes concluded that this is also unlikely, largely for similar reasons to the first conclusion.

Third, Blakes found that post-secondary institutions likely do not have a legal obligation to “proactively” disclose information on students’ legal status to the government. In other words, the law does not require U of T to alert the government whenever it finds out about a student living in Canada without valid documentation. A significant exception to this, however, is that universities would be obliged to provide this information if a court ordered them to do so.

Immigration lawyers Elise Mercier and the late Francisco Rico-Martinez, along with Sean Rehaag, director of the York University Centre for Refugee Studies at Osgoode, reached similar conclusions in a research paper published under Osgoode Legal Studies.

But the authors of this paper go further. Even if a university is found guilty of breaking the law for admitting students with precarious immigration status, they argue, well, too bad: “This is one of the limited sets of circumstances where pushing back against the law – and even breaking the law if necessary – would be warranted,” the paper reads.

The Varsity reached out to U of T to ask why the university has not yet implemented such a program and whether it plans to in the future. The university declined to provide any direct response to these questions.

“We are engaging in conversations and consultations to understand the particular educational barriers that people with precarious immigration status face and possible models to address them. Discussions on this issue are ongoing and no decisions have been made,” a university spokesperson wrote to The Varsity.

Fighting for access at U of T

Trotz put it her own way in an interview with The Varsity. “It’s not as if U of T would suddenly have its funding or its license yanked, [or be] thrown in some kind of National University Jail… that’s just not how things work,” she said.

Trotz and Macklin have been advocating for an access program at U of T through the working group for the past five years. Trotz said that the initiative came out of an event following shortly after the Sanctuary Scholars program’s launch at YorkU in 2017. Trotz recalled that community members from George Brown, Seneca College, and TMU had all come together to discuss ways to expand access to higher education to people with precarious immigration status in the wake of YorkU’s leadership.

Over the years, Macklin said, the working group at U of T has made much progress “internally” — gathering fellow staff, faculty, and students to support the cause, mainly through word-of-mouth. Macklin also said that lower-level administration, such as the leadership from the various colleges, have shown enthusiasm for the idea.

But Macklin said the working group has not gotten through to the university’s senior administration, which has the final say on the matter. “We had been trying to have conversations with [them] about this, and they really hadn’t progressed,” Macklin said. Those attempts at conversation, she noted, have mostly focused on the concerns about legal repercussions, although the group brought Blakes’ opinion to U of T’s senior administration to consider.

When asked whether and how the university planned to collaborate with the working group in the future, a U of T spokesperson provided no direct response.

A symptom of a larger issue

Part of a more permanent solution to accommodating students with precarious immigration status might include addressing how Canada’s immigration system is set up in the first place.

Thousands of students in Toronto alone graduate from Canadian high schools, only for fears of deportation — and the restrictive rate of international tuition — to bar them from enrolling in colleges or universities.

The IRCC tends to prioritize allowing newcomers to Canada on a temporary and conditional basis over pathways to permanent residency. This is part of why migrants’ rights groups have been calling for years on the federal government to implement a regularization program, in which everyone who has been in Canada for a certain minimum period of time is granted permanent residency in the country.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told his government to start looking into regularization options over a year ago, but the government’s progress on regularization has remained unclear. Organizations have continued to push for the government to implement such a program; in May 2023, the chair of the immigration law section of the Canadian Bar Association recommended that it regularize immigrants without valid immigration status already in Canada.

The result is essentially that many people in Canada are stuck in limbo for most, if not all, of their lives. Pole explained that without access programs like those at YorkU and TMU, students have limited options. They generally need to cross their fingers that they can acquire PR status on “humanitarian and compassionate grounds,” as defined by the IRCC, if they want to be able to go to university with the rest of their high school graduating class.

But doing so is essentially like playing a game of Russian roulette. A 2020 investigation from the Toronto Star found that attempting to receive PR status on “humanitarian and compassionate grounds” has a near “40 per cent chance of failure” — and that failure likely means that the IRCC deports the applicant.

If students decide not to pursue PR, they can try to apply for a study permit, which would then mean the university they apply to classifies them as an international student and charges them international tuition rates. International students across the country pay, on average, two to five times the tuition fees of domestic students. At U of T, international students pay almost 10 times the tuition of domestic students.

Looking ahead

The Varsity asked U of T about whether it plans to work on programs for students with precarious immigration status. U of T’s spokesperson pointed out a number of existing programs the university has implemented to expand financial access for students with impediments to higher education — although none directly addressed the issue of undocumented students’ legal access to a university education.

U of T is a partner university in the Student Refugee Program (SRP), which connects refugee applicants with sponsors in Canadian universities. The program works within an official agreement that the SRP’s parent organization, the World University Service of Canada, maintains with the IRCC. It allows students arriving as refugees through the SRP to obtain PR status.

The spokesperson also pointed to a number of financial aid resources available to students who are already registered at U of T, including its expansion of the University of Toronto Advanced Planning for Students program and its financial aid opportunities for international students.

One of the programs it mentioned was the Scholars and Students at Risk Award Program, which is a grant of up to $10,000. According to its eligibility criteria, the award is available to students whose higher education has been impacted by volatile political developments outside of Canada – this includes students who have been refugees within the past five years. The program strictly provides financial aid, not immigration-related aid.

The spokesperson also pointed to the initiative it recently announced to entirely cover tuition for students from nine First Nations communities.

In the meantime, the working group is still advocating for an access program. It’s putting on a panel event on November 23, which is open to members of the U of T community and leaders from other universities. Trotz told The Varsity in an email that the event aims to facilitate discussion across leaders at Ontario universities on how to design and implement these access programs.

For Trotz and Macklin, the matter of implementing the program does not come down to legal technicalities or financial concerns.

“No matter what’s going on with their immigration, no matter what’s going on in their lives, the desire to go to school always comes out in front,” Aberman said. “It’s always just what amazes me.”