Content warning: This article discusses death, genocide, antisemitism, anti-Palestinian racism, and recent and ongoing violence in Gaza and Israel.

In response to Hamas’ October 7 attack, Israel destroyed Gaza’s Al-Watan Tower, which housed several media outlets and telecom service providers that supplied internet access, thus leading to an internet outage. On October 27, after a continued onslaught of Israeli air strikes, Gaza’s already delicate connectivity was further snuffed out as Israel began its ground operations. And, between the drafting and publication of this article, on November 5, Gaza lost communication another time as Israeli troops encircled Gaza City.

Erika Guevara-Rosas, senior director of research, advocacy, policy and campaigns at Amnesty International, emphasized that a “communications blackout” makes it difficult to ascertain “evidence about human rights violations and war crimes being committed against Palestinian civilians.” Additionally, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) warned that the “news blackout” could lead to the spread of “propaganda, dis- and misinformation.” Combined with the scarcity of water, food, and medicine, the clampdown on Gaza’s internet only puts Palestine at what a group of independent United Nations (UN) special rapporteurs referred to on November 2 as a “grave risk of genocide.”

I believe that alongside Israel’s internet blockade, Meta’s suppression of online content about Palestine and assaults against journalists by Israeli forces all create a concerning pattern where freedom of expression balances on the brink of complete annihilation.

Political discourse and media giants — a sticky web

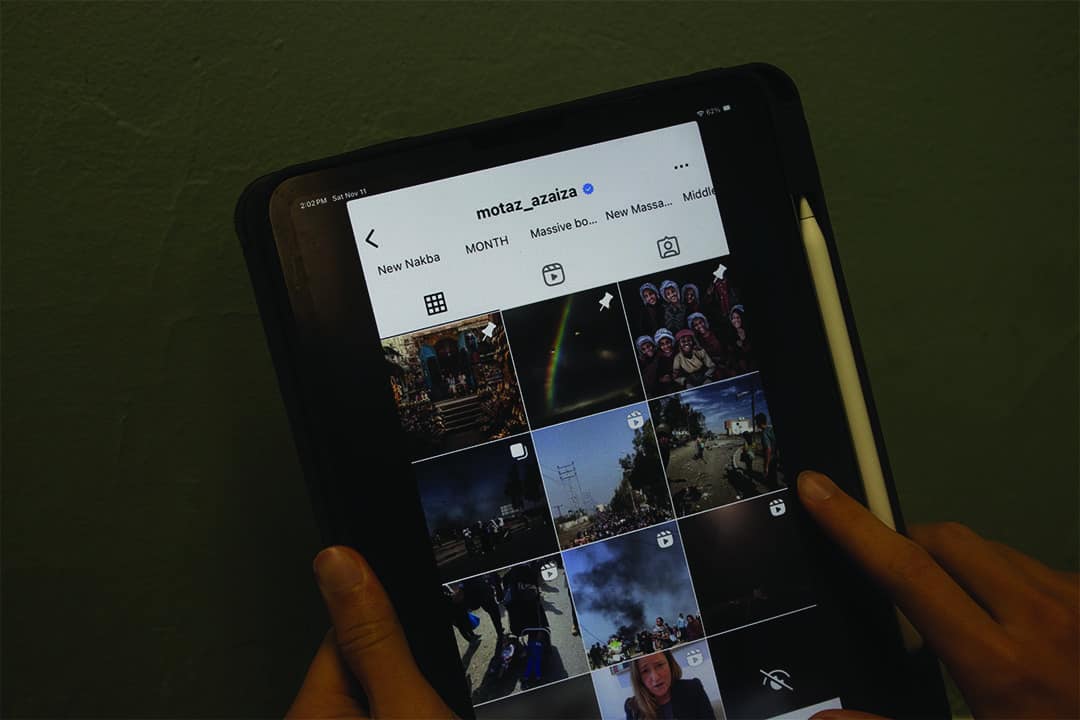

The blockade of communication severely interferes with journalistic processes. With no safe spaces to do their job while struggling against internet outages, Palestinian media has been largely fronted by Gazan journalists reporting from the ground on platforms such as Instagram. Among others, journalists Motaz Azaiza, Plestia Alaqad, and Bisan Owda have caught the attention of international viewers.

However, even the voices of journalists on social media seem to be stifled by media giants. Users are accusing Instagram, owned by Meta, of suppressing viewership on pro-Palestinian posts, removing these posts, or even ‘shadowbanning’ — obscuring content without official notification — Palestinian content creators. Yet, the October attacks are not the first time that media giants have shown prejudice against pro-Palestinian content. Meta published an internal review which showed that their 2021 policies had an “adverse” impact “on the rights of Palestinian users to freedom of expression” and that there was an over-enforcement of Arabic content.

In an interview, Mariam El-Rayes, a Palestinian student at U of T, told me that users are not seeing her Instagram stories when she posts about Palestine. When she posted random images in between her stories about Palestine to increase the chances of her stories being visible to her followers — a method known as an ‘algorithm break’ — she discovered something strange. She provided screenshots to show there was a significantly higher number of views on her ‘algorithm break’ stories than on her previous stories about Palestine — 32 versus 51 views — despite the fact that the stories were all public and that Instagram stories must be viewed in the chronological order of posting.

Accusations of platforms suppressing Palestinian news have led people to find ways to trick the algorithm, including posting ‘algorithm breaks’ as above or adjusting keywords, like ‘P@lestine’ or ‘Isr*el’, to avoid triggering censorship. The media siege can only serve to compound the humanitarian siege in Gaza, smothering the news before it can reach an international audience.

Responding to user complaints, Meta released a statement clarifying that “Hamas is designated by the US government as both a Foreign Terrorist Organisation and Specially Designated Global Terrorists. It is also designated under Meta’s Dangerous Organizations and Individuals policy. This means Hamas is banned from our platforms, and we remove praise and substantive support of them… while continuing to allow social and political discourse — such as news reporting, human rights related issues, or academic, neutral and condemning discussion.”

While Meta is entitled to create its own guidelines about organizations it judges to be dangerous, any censorship of content that condemns the killing of Gazan civilians without mentioning Hamas dangerously conflates advocating for Palestinian human rights and supporting of militant groups. Hamas’s killing of 1,200 Israelis is reprehensible, but so is the Israeli Defense Force (IDF)’s killing of over 12,000 Palestinians since October 7, as of November 11.

Shooting the messenger in a big blue vest

An even more direct interference with freedom of expression and the press is when journalists are killed and assaulted. As of November 10, 35 Palestinian, five Israeli, and one Lebanese journalists have been killed since October 7. The CPJ reported that BBC journalists who showed their press cards were “dragged” from their vehicles marked with ‘TV’ on October 12 and held at gunpoint by the Israeli police.

Dissenting Israeli journalists are not safe either. At least a dozen people surrounded the home of an Israeli commentator who expressed concern about Gazan civilian deaths, shouting “traitor” and firing flares at him, The New York Times reported.

On October 16, Israel proposed emergency regulations that would grant its Communications Minister the ability to halt media broadcasts that harm military or national morale. Under Israel’s proposed rule, officials have threatened to close the local offices of Al Jazeera, a Qatari news organization. Just nine days later, Al Jazeera reported that an Israeli air raid killed the family of its Gaza bureau chief, Wael Al-Dahdouh, despite their being in Gaza’s ‘safe area.’ No major news outlets have suggested this was an act of intentional punishment, but the IDF has also come under fire for its treatment of Palestinian journalists prior to this incident.

The United Nations concluded that in 2022, Israeli soldiers killed Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh “without justification under international human rights law,” despite the IDF denying responsibility for a year and even accusing Palestinians of the murder. She was murdered while wearing a protective vest labelled “PRESS.” Simultaneously, the CPJ found that the IDF systematically evaded accountability in 20 journalists’ deaths over two decades, launching investigations that never resulted in prosecution or punishment.

Although it is unfortunately common for journalists to get caught in the crossfire during armed conflict, journalists are specifically protected under the Geneva Conventions. An intentional killing of a journalist is a war crime. It feels almost banal to be writing a Comment piece where one of the central opinions is that killing journalists is bad. But, troublingly, it is difficult to actually charge a state with this crime when it claims journalists were killed “accidentally,” as the IDF did in the case of Akleh.

The freedom of the press and freedom of expression are core tenets of international human rights. In an age when media giants can covertly censor certain political stances and when journalists are under attack, I ask readers to be extra conscientious of the content they consume. And, in solidarity with Palestinian students at U of T and everyone else involved in human rights advocacy, I urge you to keep posting about what is happening. If we have an online platform, we should use it as a flicker of light within the darkness of Palestine’s media blackout.

Charmaine Yu is a third-year student at Trinity College studying political science and English. She is an editor-in-chief of The Trinity Review and the What’s New In News columnist for The Varsity’s Comment section.

If you or someone you know has experienced harassment or discrimination based on race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship and/or creed at U of T, report the incident to the Anti-Racism and Cultural Diversity office: https://antiracism.utoronto.ca/help/.

You can report incidents of anti-Muslim racism through the National Council of Canadian Muslims’ Hate Crime Reporting form at https://www.nccm.ca/programs/incident-report-form/, and antisemitic incidents at U of T to Hillel U of T at https://hillelontario.org/uoft/report-incident/.

If you or someone you know is in distress, you can call:

- Canada Suicide Prevention Service phone available 24/7 at 1-833-456-4566

- Good 2 Talk Student Helpline at 1-866-925-5454

- Connex Ontario Mental Health Helpline at 1-866-531-2600

- Gerstein Centre Crisis Line at 416-929-5200

- U of T Health & Wellness Centre at 416-978-8030

If you or someone you know has experienced anti-Muslim racism or is in distress, you can contact:

- Canadian Muslim Counselling at 437-886-6309 or [email protected]

- Islamophobia Support Line at 416-613-8729

- Nisa Helpline at 1-888-315-6472 or [email protected]

- Naseeha Mental Health at 1-866-627-3342

- Khalil Center at 1-855-554-2545 or [email protected]

- Muslim Women Support Line at 647-622-2221 or [email protected]

If you or someone you know has experienced antisemitism or is in distress, you can contact:

- Hillel Ontario at [email protected]

- Chai Lifeline Canada’s Crisis Intervention Team at 1 (800) 556-6238 or [email protected]

- Jewish Family and Child Services of Greater Toronto at 416 638-7800 x 6234

The Hamilton Jewish Family Services at [email protected]

No comments to display.