Is your undergraduate degree program highly competitive? Are you connecting with good job prospects as you near graduation? If so, chances are you probably contribute more to U of T’s revenue than the average student.

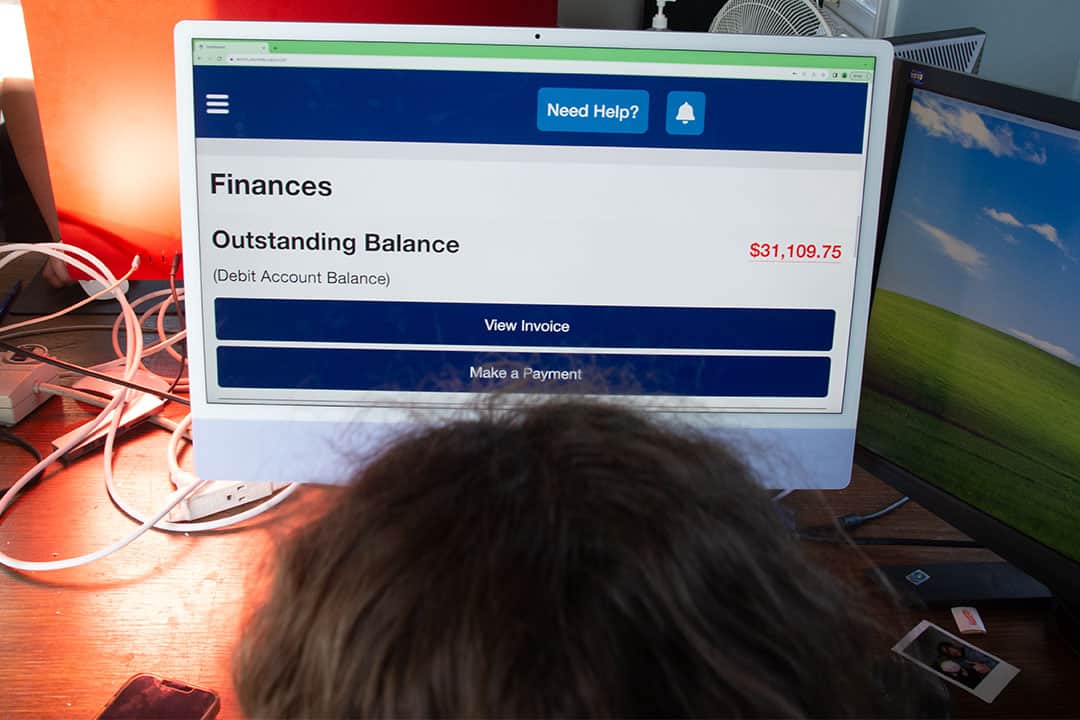

U of T students in degree programs like Engineering and Rotman Commerce have to pay a higher rate of tuition than the average student in the Faculty of Arts and Science. While the Ontario government generally limits how much universities can charge in tuition, its tuition fees policy classifies programs like engineering and commerce as “high-demand.” U of T operates per these guidelines, which result in significant disparities in student fees — a Rotman Commerce domestic student pays $9,800 more in program fees than a general student in the Faculty of Arts and Science.

The history of “high demand” tuition

Ontario’s regulatory scheme for tuition fees changed dramatically between 1997 and 1998. Before that, the government regulated all degree programs’ tuition the same, regardless of demand. Within this framework, universities had the discretion to set tuition between a minimum and maximum amount.

However, in 1998, the government decided to deregulate the tuition of some programs altogether. Specific criteria dictated which programs could sidestep typical tuition regulation: there had to be an especially high demand to study the subjects taught in the program, particularly strong employment prospects for current students, and high potential income for graduates.

Ontario called the marginal increase in tuition paid by students in deregulated programs “additional cost recovery fees” — presumably, to account for the higher financial burden of operating such programs, such as professors’ salaries.

The only constraints the province put on deregulated programs were that tuition could increase by no more than 20 per cent each year. Furthermore, enrolment in all deregulated programs could only amount to a maximum of 15 per cent altogether of the university’s total undergraduate enrolment.

Then in 2004, Ontario started regulating tuition for all undergraduate programs again at the same rates and instituted a two-year tuition freeze. Now, the administrations of these previously deregulated programs no longer have the same freedom they did before.

However, those frozen rates still reflected years of deregulated tuition in certain programs. Moreover, student fees increase proportionately to the tuition rate that a student pays, further widening the disparity in how much these students pay in comparison to those in regulated programs.

The Ontario government also continues to make special exceptions for regulating high-demand programs; in the 2018–2019 academic year, universities could only increase tuition by three per cent for full-time students in regular degree programs, whereas they could raise tuition for students in high-demand programs by five per cent.

Student efforts to combat rising fees

Concerned about the barriers higher tuition might pose to disadvantaged students seeking to study programs like Computer Science or Rotman Commerce, student unions on campus have initiated campaigns to address this issue in the past.

The ‘Same Degree, Same Fee’ campaign was an initiative led by the Computer Science Students’ Union in 2021 that brought in support from the Arts and Science Students’ Union (ASSU) and the University of Toronto Students’ Union. Spurred by the fact that domestic students in Computer Science or Data Science had to pay 87 per cent more in tuition than other science students in the Faculty of Arts and Science, these groups called for the university to set these programs’ tuition at the same level as other science programs.

Over 600 students signed the campaign’s petition, which cited students’ mental health and the inaccessibility of the above programs to marginalized students. When The Varsity first reported on the campaign in 2021, a U of T spokesperson wrote in a statement that they were open to hearing comments from student union leaders within university governance processes. However, the CSSU asserted at the time that these invitations were essentially meaningless because the kind of changes they were advocating for did not take place in these stages of the university’s decision making.

The campaign did not succeed, and computer science students continue to pay 87 per cent more tuition than other Arts and Science students. “The University administration refused to participate with the campaign,” wrote current ASSU President Anusha Madhusudanan in a statement to The Varsity.

A U of T spokesperson wrote to The Varsity that decisions to reduce or freeze these program fees “currently rest with the government.”

Alleviating the financial burden of studying a ‘high-demand’ program

While U of T does not have the same freedom to raise tuition for high-demand programs as it did before, students studying these degrees continue to face skyrocketing fees.

Student groups continue to advocate for greater financial assistance for students in these programs. For example, the ASSU has increased funding for its various awards and bursaries to better support students facing high tuition. It also hopes to offer a “Deferred Exam Fee Grant” starting this December to subsidize the costs of deferred exams.

These may not be direct solutions that address the disparity in tuition between various programs, but they can still indirectly aid students by offsetting academic costs like textbooks and public transit fare. Nevertheless, the ASSU has not given up yet. Madhusudanan stated that the union plans to reconfigure its campaign in the future and present it to U of T’s administration again.

No comments to display.