Content warning: This article has mentions of death and sexual assault.

In the endless and ever-changing linguistic landscape where TikTok and other short-form media reign supreme, I often reflect on how utterly incomprehensible we must be to past generations. Every so often, I try to show my mom a funny video and find myself drowning in endless terms to define, trends to explain, and unintuitive humour to articulate.

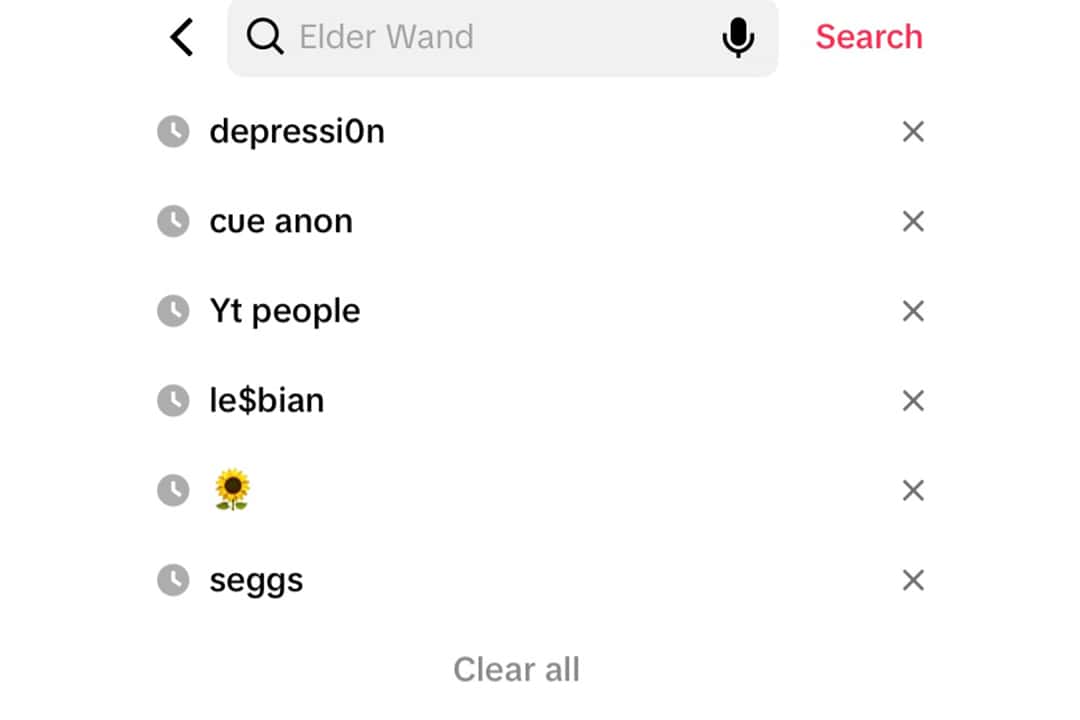

From this rapidly evolving social media culture, we see the rise and resurgence of new terms and ideas. Concepts like “rizz,” “gaslighting,” “gatekeeping,” and “beige flags” pop up out of nowhere, skyrocketing to become common knowledge in a matter of days. TikTok’s effect on language goes beyond introducing new terms, often inventing replacements for existing terms. Triggering and sensitive topics like death or sexual assault are replaced with softer replacements like “unalive” and “mascara.”

Many dub this phenomenon as “algospeak,” which are codewords used to circumvent algorithms that platforms introduce to filter out terms that may be sensitive or violate app rules. While the origins of algospeak are clear, the hyper-connectivity of the internet can conclude a different explanation for its pervasiveness in TikTok vocabulary. In my view, algospeak is not simply filter evasion, but a natural, albeit accelerated, cycle of linguistic evolution.

The way our learning causes language to drift

Language is an ever-evolving aspect of human society. A study from the University of Reading in England examined the evolution of words across modern Indo-European languages and found a high similarity among very common words — such as “three” — across languages, indicating that frequently used words evolve very slowly. However, less commonly used words — for instance, even the words for “bird” —- showed wide variations in sound across languages.

From the trends shown in the study, the researchers estimate it could take only 750 years to replace lesser-used words. These historical changes in linguistics took effect in pre-industrial Eurasia, too. But with the immense interconnectivity the internet brings, incremental changes in vocabulary that would have had to accumulate over generations and permeate hundreds of kilometres can now be in a constant state of rapid cumulative change fueled by the massive exposure TikTok allows.

The method of social learning that humans employ is crucial in the evolution of language. Compared to close primates, human children have a heightened tendency to learn by high-fidelity imitation, that is, by copying all actions demonstrated to them, even when unnecessary to their goal. This blind imitation is how humans can learn so efficiently because even when we do not fully understand the rationale behind actions, we faithfully copy them. This can naturally be extended to language: children are often scolded for repeating profanity, but they are simply copying others.

Studies also show that children learn languages spontaneously and far quicker than adults, and only at around age 12 are these abilities assumed to start diminishing. Accordingly, a Statista report revealed that 36.2 per cent of worldwide TikTok users are between the ages of 18 to 24.

However, this data cannot be fully representative of the population. The previous source claims to account for 100 per cent of TikTok users, but it has no statistics for users under the age of 18. This is in spite of the fact that TikTok’s terms of service allows users aged 12 and up, and even younger children are allowed a censored version in the US. Although this data does not account for the large population of users under 18, one online marketing company called GrowthDevil estimates that up to a quarter of US TikTok users are in the age group 10 to 19. With so many young, spontaneous language learners, new terms and phrases can spread like wildfire.

Algospeak as the natural cycle of linguistic evolution

Thus, I see algospeak as nothing new. It is just a set of new words to be learned, another generation of language. Children will copy them with no knowledge of their original purpose.

The conscious replacement of “offensive” or sensitive words is not an inherently new concept either. Euphemism has existed as long as language itself. The earliest recorded instance of euphemism is the word “bear,” which was coined with the superstition that the true word for bear would summon the animal. The word evolved from the Old English word “bera,” akin to the word “brūn,” meaning brown. Until researching this, I had no idea that bear was a euphemism, making it a salient example of how words naturally evolve, and conscious replacement can, with time, be wholly adopted so that their original intent is forgotten.

The loss of intent does not have to take place over millennia. I had always thought that instances of algospeak were simply users trying to be conscious of sensitive topics. I have seen posts across the internet marked with “trigger warnings” to alert potentially sensitive topics, euphemisms used to soften horrible truths, and I figured words like “unalive” were simply a humorous extension of these intentions.

As children and others like myself — users not privy to the ins-and-outs of boosting engagement and dodging bans when posting TikToks — are exposed to the results of algospeak, we will tend to adopt these terms without questioning or understanding their original intent. Now, inevitably, when TikTok decides the next arbitrary word to filter out, a child will learn the algospeak word for it as if it were a synonym, like any other word — a natural extension of linguistic evolution.

Max Zhang is a first-year student at Woodsworth College, studying computer science.