Danny and the Deep Blue Sea is a tale of love and woe; two strangers, Danny and Roberta, meet at a bar and face the fateful consequences of their encounter, which spiral into violence and vulnerability. Though both characters follow an archetype — unstable individuals angry at the world and their circumstances but secretly in need of love — the story never feels like a cross into cliché. Between December 1–3, the UC Follies — University College’s theatre troupe — put on John Patrick Shanley’s Danny and the Deep Blue Sea at Theatre Passe Muraille.

The ‘alternative’ Passe Muraille theatre offered little in the way of set design for this particular play, but its outer appearance, industrial and nondescript, masks an ingenious story inside. The tight, asymmetrical space, which holds a stage in the corner of the room, is almost claustrophobic, drawing the audience into the middle of the characters’ lives. Costuming, makeup, lighting, even sound — all distractions are minimized until the viewer is alone in a wide ocean, with nothing to hold onto except the play’s characters, who are equally lost.

Like all good stories, it begins in a rundown bar — this one is in the playwright’s home, the Bronx. In fact, every aspect of the play seems to be influenced by Shanley’s life; he worked an odd string of jobs, including bartending.

Danny and Roberta exist in the bubble of their first meeting, dancing back and forth between the initial violence and the spark of their first barroom interaction, but never exiting that moment. Ethically dubious and at times painful to watch, trauma and its effects act as a third character in the pair’s story. It occupies such a large space in the small theatre that there isn’t much room for healing.

However, the play is not a glorification of abusive relationships and childhood trauma; in fact, it opens up room for a difficult conversation about mental health. First performed in 1984, in an era which lacked the privilege of the language we have today, the play is truly a story of piecing one’s life back together against the odds. Despite lacking the right words for it, Danny and Roberta navigate their emotional baggage together. The actors do a fantastic job hinting at the tensions below the surface as they do so.

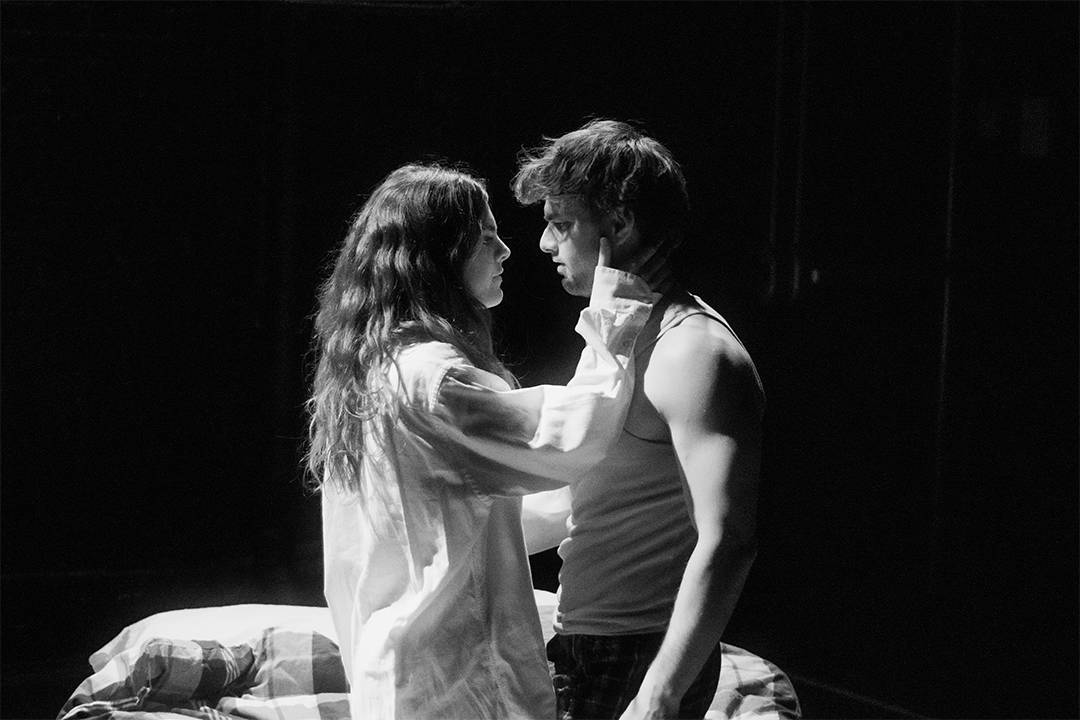

John Cleave, a U of T student and the play’s director, described his hands-off approach: his interpretation is defined not just by making artistic choices but also by not making them. Cleave emphasized the emotional dynamics of the two main characters rather than flashy production. The physical distance between the actors — who are farther apart while they meet as strangers and who grow closer as they learn more about each other — contributed to the audience’s sense of being inside their lives, feeling what they feel. As for the actors, they were loud, brash, and, at times, took it out on the audience — a totally immersive experience. Even in silent moments or gaps in conversation, the actors conveyed their characters’ inner turmoil in a raw and beautiful way.

Danny and Roberta, like most people we meet in this world, are not necessarily good people; they are loud, rude, and angry, and they often hurt each other verbally and physically. But are they bad?

According to Cleave, Danny and Roberta shouldn’t work, but they do. Perhaps there can be love even in the harshest places, as long as there is also forgiveness. It’s a scrappy, painful process, but Danny and Roberta absolve each other of their sins, proclaiming the final words: “I forgive you.”

No comments to display.