U of T was recently named the world’s most sustainable university by the QS World University Rankings: Sustainability 2024. As a student at U of T and a climate activist, I was horrified. Here is why.

There is broad scientific consensus about the main driver of climate breakdown: the production and consumption of fossil fuels. Since the 1970s or earlier, the fossil fuel industry has known that it is causing climate change. Not only has the industry failed to mitigate the climate crisis, but it has also actively promoted climate change denial.

The “Canada’s Big Oil Reality Check” report by Environmental Defence Canada and Oil Change International shows that Canadian oil companies still do not have serious plans to meet net zero, despite knowing about climate change for decades. Beyond direct fossil fuel extraction companies, Canadian banks are direct enablers of the fossil fuel industry. They are some of the biggest funders of fossil fuel projects in the world.

Today, U of T has many ties with fossil fuel industry actors. Listed below are just a few of these ties.

U of T’s Boundless fundraising campaign has received donations from numerous fossil fuel companies, including a donation of between $100,000 and $999,999 from Husky Energy Inc. — part of Cenovus Energy — a donation of between $25,000 and $99,999 from BP Canada Energy Company, and a donation of between $25,000 and $99,999 from Suncor Energy Inc.

In November 2022, U of T’s Climate Positive Energy Initiative hosted a Climate Economy Summit. The event was sponsored by Enbridge, a Canadian multinational pipeline corporation, and Imperial Oil, a fossil fuel company that has been a historic leader in campaigns of climate denial.

In August 2022, I attended the Climate Positive Energy Institute’s inaugural Climate Positive Energy Research Day. One keynote speaker for this conference was Graham Takata, the director of climate change at BMO Global Asset Management. His speech focused on how the Bank of Montreal is engaging its assets under management toward net zero. In truth, however, BMO has financed the global fossil fuel industry with about 138.380 billion USD between 2016 and 2022, according to Banking on Climate Chaos’ 2023 Fossil Fuel Finance Report.

Fossil fuel ties at U of T date back to at least the early 2000s. For instance, in 2002, TransCanada PipeLines Limited donated $500,000 to U of T to help set up the TransCanada PipeLines Chair in Aboriginal Health and Wellbeing. Its mandate was to “[conduct] health research, [develop] education programs in aboriginal health, [raise] awareness of the importance of aboriginal health research, and [provide] academic leadership for aboriginal health research students.”

Unfortunately, this chair position is a prime example of ‘redwashing,’ where a company or institution co-opts narratives around Indigenous reconciliation to improve its image at a purely superficial level. In reality, TransCanada, now TC Energy, has a history of violating Indigenous sovereignty for its fossil fuel transportation projects.

The list goes on, but I will stop for now. The point I am making is that U of T, while posing as a leader in sustainability, is an active partner of fossil fuel companies. I contend that by accepting these partnerships, U of T implicitly endorses the activities of fossil fuel companies and announces them as worthy partners of academic institutions.

Donations can allow the fossil fuel industry to gain influence over internal decision-making, research directions, and messaging by the university. Energy research funded by fossil fuels is proven to be biased in favour of industry interests, often promoting natural gas as a climate solution.

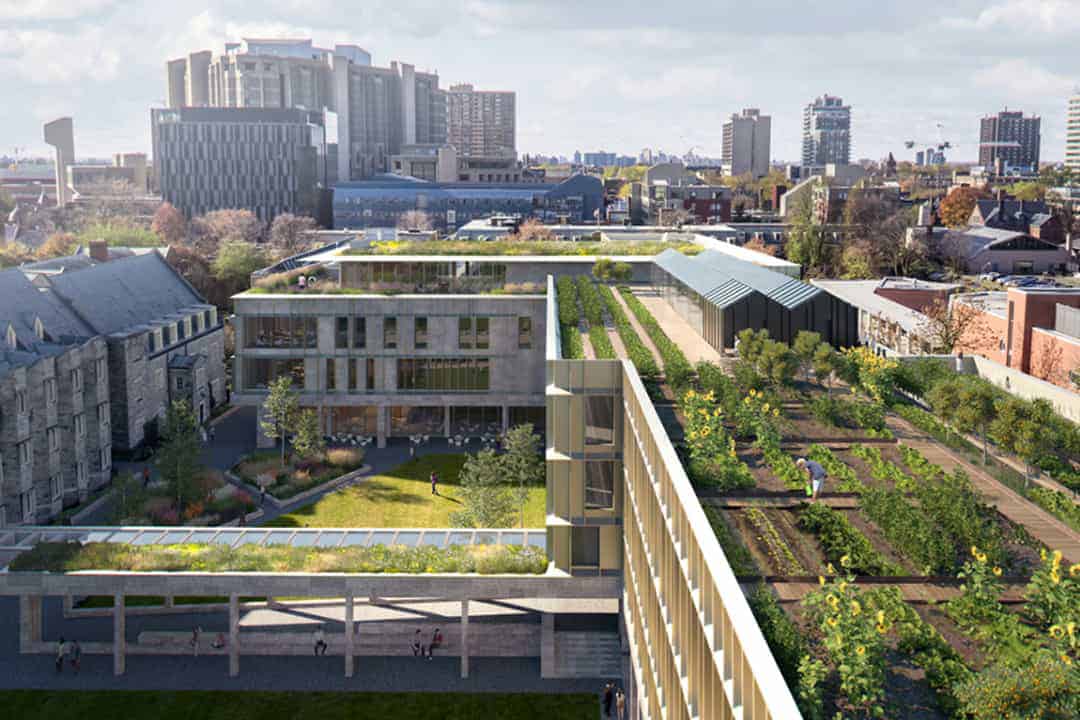

The QS World University Rankings for Sustainability looks at environmental impact, social impact, and governance. In the article about its ranking, U of T boasts that it “has implemented a number of infrastructure projects aimed at achieving the goal of becoming climate-positive by 2050,” and that “30 per cent of all undergraduate courses at U of T in 2023-24 have a sustainability orientation.” These are undoubtedly important steps, but initiatives to improve localized carbon footprints and climate education cannot, in my opinion, make up for U of T’s active legitimation of the fossil fuel industry.

To me, a positive environmental impact means not actively contributing to the climate crisis threatening future generations. A positive social impact means not accepting money and providing social license to operate with the fossil fuel industry, which often acts without Indigenous consent and causes human rights crises from climate breakdown. Good, impartial, and sustainable governance means, at the least, not having direct links with the primary industry that lobbies to delay climate action. U of T is succeeding on none of these metrics.

If U of T is serious about helping to mitigate the climate crisis, I believe it must cut ties with the fossil fuel industry.

Amalie Wilkinson is a fourth-year student at University College studying international relations and peace, conflict and justice studies. Xe is a member of the Fossil Free Research campaign within Climate Justice U of T.

No comments to display.